A Safe Space for Stupidity: William Kentridge's Masterclass at Animafest Zagreb 2023 (GoCritic! Review)

“If we were sufficient in ourselves, we wouldn't have the need to create,” says William Kentridge, the South-African multi-disciplinary artist who has just received a lifetime achievement award at Animafest Zagreb 2023. The “gap” or “lack” in ourselves that pushes us to make art, he fills with animation, drawing, theatre, and many other forms of self-expression, the results of which have a lot to do with reflection upon oneself and one's surroundings.

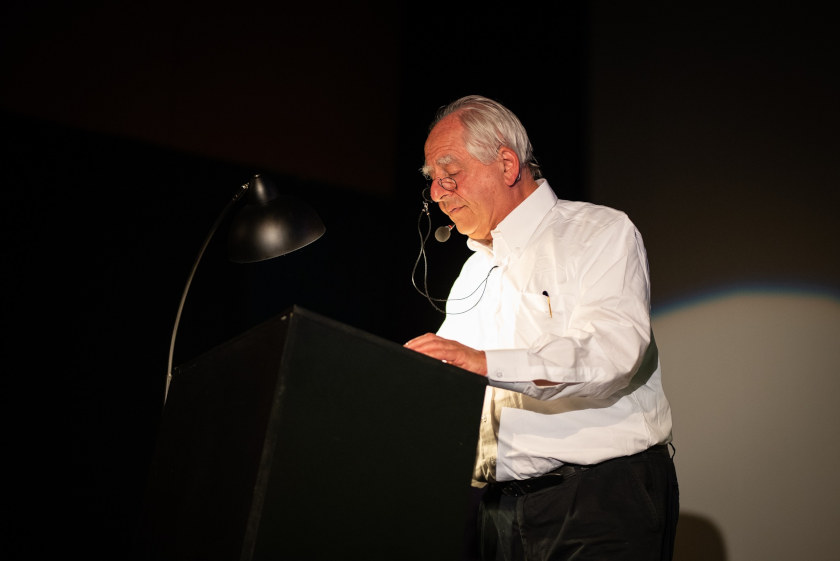

During the festival, there were multiple events of which Kentridge was the focal point, the main attraction being his masterclass. Even before the doors opened, a voice in the surprisingly crowded lobby loudly expressed delight at the number of people interested in an animation masterclass. It might have seemed surprising – until they found out that Kentridge is not only an esteemed artist but also a witty storyteller. His jokes lightened the mood, but not the weight of his wisdom, and even as the large hall grew hot and stuffy, the audience listened intently.

The main focus of his 90-minute lecture was his artistic process. But it was not a speech on how a particular artist does his work; it was a rumination on space and thought. He considered how we think through our bodies, how physical presence is positioned in space, how we move, and how we use particular muscles to make art. For him, thinking is a physical process, so space is of utmost importance.

Kentridge uses the word “studio” to describe this thinking space. How it is arranged is essential, and how it can help us both as a physical room or a desk and as a dedicated place for specific actions. The “studio is a safe space for stupidity,” he says, defending the right to be wrong, because “less good ideas are important too”. This seems to fit right into place in a world that is moving away from grand narratives, grand gestures, and gigantic solutions to problems. It is now fragmented yet connected.

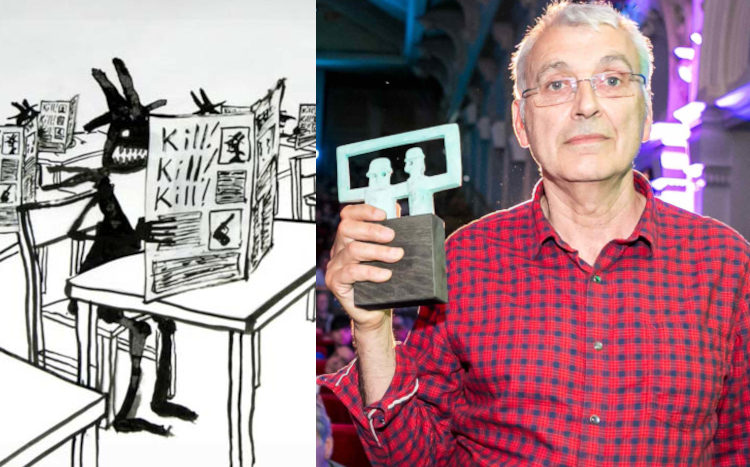

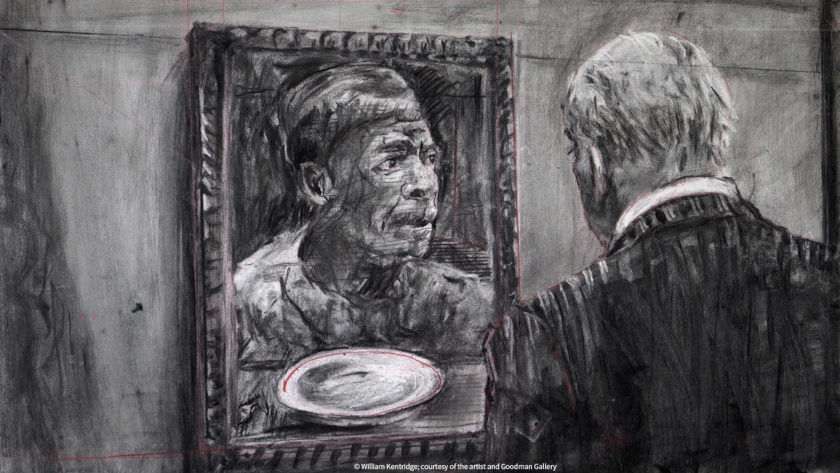

This notion emerges in his works in multiple forms. One is the post-colonial viewpoint: instead of continuing a general, mainstream narrative, he turns to the voices of the oppressed, telling black South African stories and using black actors. Second, the lack of predictability in his workflow creates unexpected links between different concepts. For example, the frequently recurring, differently loaded motif of the coffee pot is the result, he tells us, of a random decision one morning to take his coffee with him into the studio. Third, there's the relationship between image and text, where the flow of an image is often interrupted by bold text: Kentridge’s works are full of slogans, phrases that are full of meaning but which challenge our natural need to detect comprehensible patterns. This is a collage of both the artist's process and its result. Of course, one could argue that any work of art is a collage of ideas and skills, combined in an orderly manner, but Kentridge emphasizes the effort it takes to be a coherent being in the world, and this illusion of coherence travels from his personal approach to his work and back again.

City Deep by William Kentridge

City Deep by William Kentridge

No wonder Kentridge feels close to the Dada movement. Dadaists rejected logic and celebrated nonsense, continuing the idea of anti-art which subverts previous definitions and conceptions. Undeniably, there is a certain logic to Kentridge's work, but it follows the rules of chaos: first, do, and then think. His performance of Kurt Schwitters’s sound poem 'Ursonate', which took place later in the evening, also creates an illusion of coherence. He recited the forty-minute phonetic poem, also called 'Sonata in Primal Sounds', in collaboration with four musicians – a cellist, a trumpeter, a vocalist, and a keyboard player – who improvised alongside him while his animations were projected behind their backs. There is no sense in the sounds that we hear, but still our minds, Kentridge’s choice of tone, the accompaniment, and the projection, all form a narrative.

We are told that Kentridge does not plan ahead. He allows the creative process to flow and exist on its own, instead of confining it to a rational, linear progression. Charcoal, his preferred tool, with its transformative nature, represents what animation means to him. When thinking about his subjects or objects, instead of seeing them as singular units, Kentridge views them as part of a longer chain of events. The podium he now stands on is not just a podium. It is also the wood it came from, the craftsman who made it, and the firewood it might one day become. Nothing in his films is ever permanent: things shift and move, they transform into people, only to turn back into things again.

We do not know how much of the performance was truly improvised and how much had been prepared in advance, just as we do not know how much of William Kentridge's supposed creative chaos is an illusion. It might be that the answer does not matter. Kentridge says that he has to find “a way to protect my not-knowing, my uncertainty” – and his art might help us protect our own.

Contributed by: Dace Čaure

(Central Image: William Kentridge at Animafest Zagreb 2023)