‘Cutouts are asking to be animated’: Interview with Aria Covamonas, director of ‘The Great History of Western Philosophy’

At the 2025 International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR), Mexican animator Aria Covamonas world-premiered her debut feature film, ‘The Great History of Western Philosophy’, in the festival’s famed Tiger Competition. Known for her shorts ‘Socrates' Adventures in the Under Ground’ and ‘I Can’t Go on Like This by Aria Covamonas from Planet Earth’, Covamonas has a distinct strategy to her filmmaking. When you watch ’The Great History’, you might feel deeply disoriented by what you see and hear over the film’s 70-ish minutes. However, there’s a reason why one might react this way, as Covamonas directly challenges viewers to let their minds interpret.

In Rotterdam, Zippy Frames sat down with the filmmaker to decrypt this creative approach, unpacking the technique and different elements of the film, which lacked a script but instead used a “described method”.

ZF: Your film tends to avoid conveying conventional narrative meaning as we often expect to see it in feature filmmaking. What was your approach to this work?

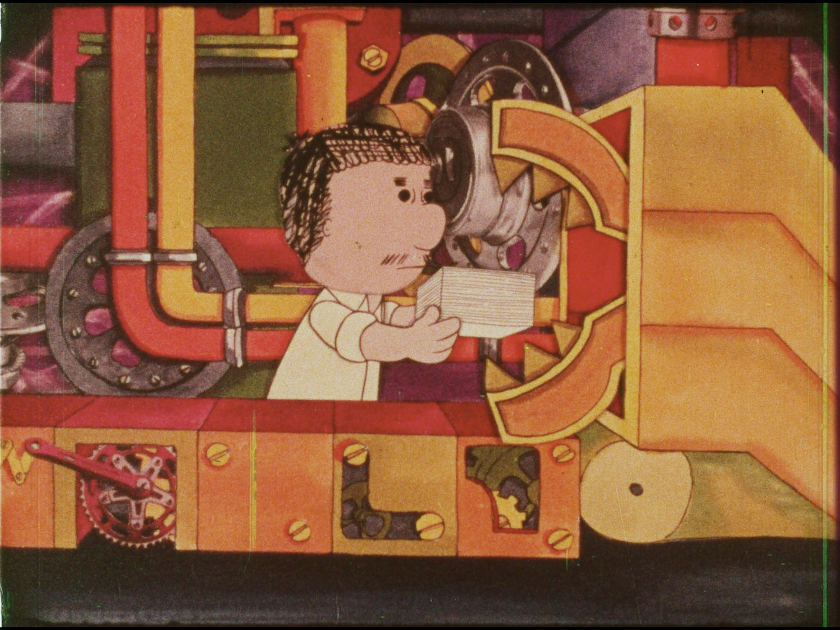

AC: The movie is an exploration of how meaning is constructed. We have this idea that a meaning appears when I say a word. I think that is incorrect. We say a word, and there are bits and a stream of words running and running. I wanted to create a machine that does that with images and pieces of pre-existing sound from other films. You just fill this imaginary machine with the images. The game is like an imaginary machine where you have a field and a set of rules. You just want to see what happens when you let this chain of significance run, and the meaning appears in that movement.

ZF: Within this imaginary machine, viewers still might recognize historical characters, characters from mythology, and so on, perhaps as suggested in the title. How did you decide to incorporate this aspect?

AC: For example, when an unconscious mind constructs a dream, it doesn’t understand the disconnection between the subconscious mind and conscious life. The subconscious mind sees our life and places things together, like the technique in the movie, to present it in a dream. That’s kind of the idea. All these characters appear because of what is available from the public domain library. It’s like in music or poetry: you have rules that you have to follow—for example, the number of syllables. You cannot use every word in the language from the vocabulary of the language, but you can use the word that fits. Making the analogy to the movie, I cannot create any image. I can use images that are available, and they dictate what will happen. I can have intentions, sure, but I am limited. The sounds and songs are cut from public-domain movies.

ZF: I wanted to ask about the sound, as many of them are cut from Chinese-language films. For someone like me who can understand the majority of this “public domain” Chinese dialog — reading the subtitles, which don’t match, was a very interesting experience.

AC: I want to know what you think.

ZF: At first, I was disoriented. I understood the dialog while trying to read the text, which initially caused me some confusion. As you said, a disconnection occurred, and the film was the bridge between the two.

AC: I was very tempted while making the movie, to just skip the subtitles. I don’t speak Chinese. I made the movie, and then had to interpret [the sound]. I put pieces from different conversations from different movies because they sounded kind of like they could be a conversation. I was tempted just to leave my interpretation outside and then you would just watch a movie in a different language. I had to make up the interpretation myself, but Chinese-speaking people would get this weird and absurd output.

ZF: Maybe I should go back and not read, but instead just listen.

AC: I think that is the best way if you can understand what is going on with the dialog.

ZF: And what about the sheer scale of collecting all of the images and sounds? Where did you start?

AC: The main archive I used was from the U.S. Library of Congress. I had a subject, and I started inputting keywords. It’s like the thing that surrealists do, “exquisite corpse”—I might not find what I want, but I find something else that gives me another idea that I have to connect to. Also, the Internet Archive has a very vast, wonderful set of archival images from books. There are a lot of small libraries that also do the same. They scan the books.

ZF: Can you talk about cutouts -your technique of choice through your films?

AC: That technique is completely stolen from Dadaist artists, specifically Hannah Höch. I kind of see her as the inventor of the technique. I am a writer, and [originally] I started by illustrating texts. The [cutout] technique calls for animation because you are making puppets. It’s one step away from illustrating with cutouts. They are asking to be animated. The film took three years [to make]. There wasn't a script, but it was presented as a described method that is about the subconscious and creating this chain of significance of images.

Watch the trailer for 'The Great History of Western Philosophy':

ZF: When you said that, the film suddenly made sense to me; if you could say that, even if it’s not meant to “make sense.”

AC: It’s the same when you dream. After the dream, you interpret what you think. This may be why it is very boring when people tell you about their dreams.

ZF: I love that your film challenges viewers' rationality and the expectation that we are constantly meant to interpret what we see onscreen.

AC: Sometimes, I didn’t know how to continue in the process because every unit is two seconds. I had to make two of those every day, so four seconds. But every unit is completely finished—sound, image, color. There is no post-production, so sometimes I don’t know how to continue. So what I did, because I had to keep working, was repeat the same movement. There is this joke in the movie, which is my favorite joke, that sometimes the same movement goes on for too long. It’s because I didn’t know what to do. Chico Marx from the Marx Brothers sometimes plays the piano [for too long], and jokes, “Oh, I am stuck!”

French MIYU Distribution handles the International distribution for 'The Great History of Western Philosophy'