Buñuel In the Labyrinth of the Turtles Review

How do you depict Luis Buñuel, one of the greatest iconoclasts in cinema, and get away with it? Surrealism, irony, dreams and realities make his work a constant inspiration, and a constant trouble to describe.

Based in the graphic novel by Fermin Solis, the project was first brought to the forefront by Spanish producer Manuel Cristobal (of Wrinkles / Arrugas la pelicula). Director Salvador Simó had to spend hours of research to isolate the necessary elements to describe what was essentially a very confined but still clearly identifiable story.

The subject matter of Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles (Buñuel en el laberinto de las tortugas, production: Sygnatia / Glow / Submarine Amsterdam / Hampa Studio) verges on the animation documentary territory. Yet even if the film utilizes both live-action (Buñuel's own 1933 Land Without Bread) and animation, it has a certain distance from the more politically-tinted Spanish/Polish feature Another Day of Life (Raúl de la Fuente and Damian Nenow, 2018). Buñuel and the Labyrinth of Turtles is more the story of a flourishing, talented but insecure artist will all kinds of questions.

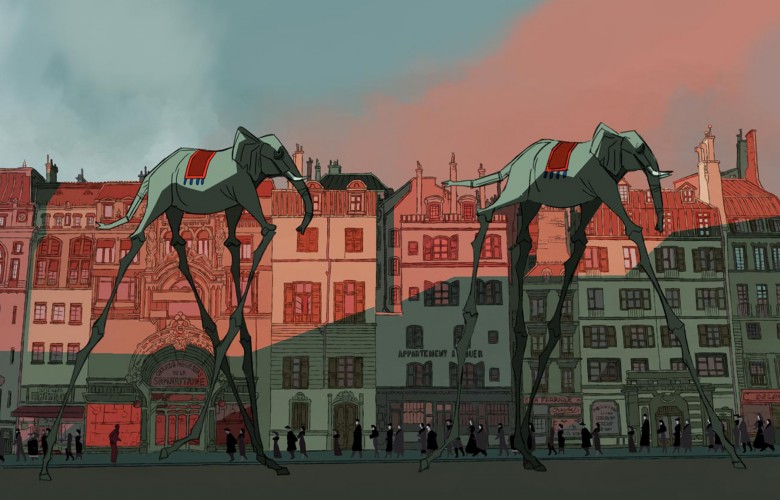

This effectively compassionate film starts with the 1930s Paris, when a theatrical screening of the Spanish director's L’Âge d’Or causes a havoc among the observers. The surrealism of the early film scenes in the fashionable Paris cafes, where surrealism is contrasted with political action, suddenly finds its bitter reflection. Surrealist Buñuel (Jorge Usón) needs to face an uncertain future, since no Parisian financier is willing to put their hands on his projects (the Catholic Church is an over-powering force). A lottery ticket and the friend Ramón Acin (Fernando Ramos) who's willing to abandon his family to accompany the young director, is the first episode that sets the film to Las Hurdes mountains in northern Spain. Buñuel will now need to prove his social commitment and talent.

For a film that needs to juggle both surrealism and documentary (as Buñuel himself did), it really balances showcasing Buñuel's own materials and narrating at the same time his own demons and dreams (hence the turtles). Even though at times the celebrated director's oeuvre really stands out from everything presented on screen, both script (co-written by Eligio Montero and Salvador Simó) and direction make sure that the life of an artist can be itself presented as out of the ordinary. The usual association of animation with animals now finds its sweet revenge here, since it is the animals that torture Buñuel in animated life; in turn, he tortures them in his real expedition.

Focusing more on the life of a film crew during shooting - Pierre Unik (Luis Enrique de Tomás) and Eli Lotar (Cyril Corral) are Buñuel's collaborators- the film needs to recreate a journey almost one century later, when poverty on screen is nothing new. It does this by concentrating not much on the episodes themselves, but on what constitutes an artistic mission. The famous reality that Buñuel seeks and will fabricate when not readily available, is here distinctively represented. The spacious barren land they have to travel (coupled with the dangerous turns to ride with their much-expensive car) here makes its presence a lot. The locals are also designed with rough outlines to look rugged and (sometimes) the fools of the village. But not everyone is a happy peasant in the film, and both officials and locals know what it is to be filmed (and sometimes can use their power or cunning to their advantage).

Still, the main focus is Buñuel himself and his troubled character compared with the more earthy (but clearly supportive) Ramón. The director's story, starts from from Calanda 1909 childhood and his fear of the father and ends up to his fear of roosters. In between, we see an irritable, talented but weak and tortured personality. Buñuel as a cinematic character is unpredictable but affectionate, humorous and a suffering child. It is to the credit of the film that doesn't shy away from some disturbing scenes -even though one would certainly welcome more sumptuous dreams and imaginative nightmare sequences (the Parisian streets nightmare sequence is a standout here). Arturo Cardelús' score can resonate with both Parisian and rural environments, and builds a sense of community all along. Whereas shadows and hues work to the film's advantage, character design (especially in Buñuel) still needs more to capture the fervor behind the man.

Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles has a bigger gamble than most independent animation features; it needs to confront both a prejudice against animation for grown-ups and a close scrutiny on the subject-matter of the film itself. By confining itself to a certain slice of life, it becomes a solid and considerate effort, almost soothing in its treatment of the celebrated director's inner troubles and external obstacles. Definitely a film to watch.

Vassilis Kroustallis