Day of the Crows (Le jour des corneilles) review: calm before the storm

What it takes to be savage? Being raised in a forest, fearful of The World Beyond might be a prerequisite, but surely there must be more than this to guarantee exclusion from humans.

Day of the Crows (Le jour des corneilles) is an adaptation of a novel by Jean-François Beauchemin, and it is directed by Jean-Christophe Dessaint (assistant director in Rabbi's Cat). The directorial makes this film a dramatic exercise on reason and savagery.

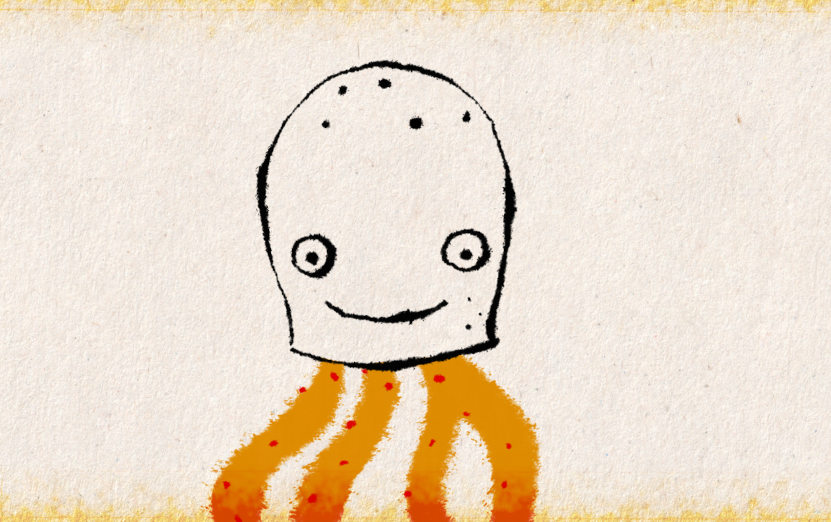

The voice of reason is here successfully attributed, against expectations, to the one least likely to have a reason. The hyper-kinetic, excited, curious and still content savage Son/Fils (Lorànt Deutsch) is the one with the willingness to depart from inherited savagery, which stems from his desperately furious, Ogre-shaped father (Jean Reno).

Son lives in a forest inhabited by calm, silent ghosts who bear animal faces. This is more than a contrast to the heartless father ("eat your prey or you become your prey"). The landscape curiously echoes the naturalistic Bambi atmosphere in its diversity, even though we are faced with a marvel of impressionism. The Day of the Crows environment never rests: from autumn to spring and winter snow it feels like animating Vivaldi's Four Seasons with force and no color palette spared.

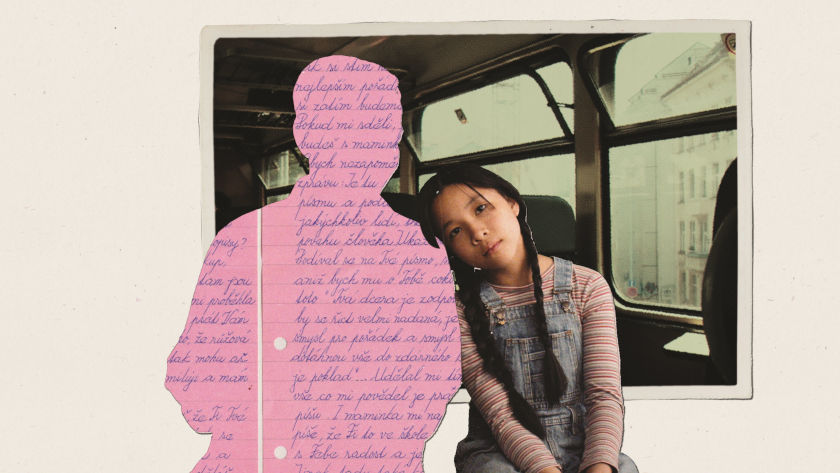

An equal force runs through the narrative (the script written by the novel writer and Amandine Taffin). The early trademark theme of a boy discontent with his environment (think of The Wizard of Oz) is successfully exploited to put the savage successfully back into the world of the humans. Son has to move to the forbidden village to aid his ailing father, and meets there a kind doctor (Claude Chabrol, in his last acting role) and his small girl, Manon (Isabelle Carré).

Τhe usual maladjustment to civilization is funny (have you ever wondered how to harpoon a fly with a fork?), but this is not My Fair Lady animation. Filthy and savage people, such as the old lady who sticks her nose into other people's affairs, are ready to intrude and offer filthy cakes (which later become food for filthy pigs). And the group of soldiers who ceaselessly shoot birds is a menace on hold.

The third act of Day of the Crows is the most impressive dramatically, and one that features the most memorable, flock of birds scene since Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds.

Son will now have to face the real problem he so hard tried to evade: his father and his past psyche. He learns how savagery can be gradually built into one's heart, and where salvation lies.

It is to the compliment of the film that gives no sugary resolution, but rests on the semi-utopian character of the forest environment to impose its own answer. In the meantime, Day of the Crows is an excellent piece of film making.

Vassilis Kroustallis