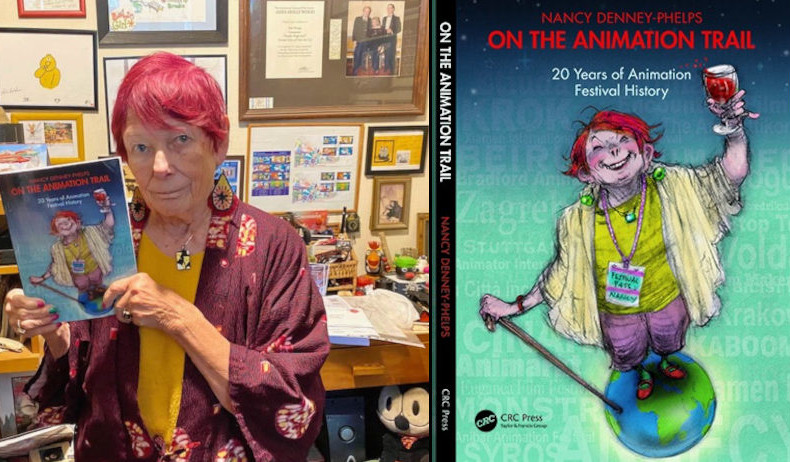

Animafest Zagreb’s Reanimation of Aleksandar Marks (GoCritic! Review)

We need more Marksists! Wrongly fallen into oblivion – even in his native Croatia which has a mammoth legacy in animation – director-cartoonist-animator-screenwriter-illustrator Aleksandar Marks (1922 - 2002) deserves our post-mortem apologies. Although he left an indelible mark on the Yugoslavian film scene and on his Zagreb School of Animation peers - most notably on Oscar-winner Dušan Vukotić - Marks is no more than an occasional sidenote in film history. Watching his arresting and often hyper-stylized work at this year’s Animafest Zagreb, this seems an unfair but perhaps ironically fitting fate for an uncompromising storyteller whose characters themselves tended to exist on the margins of society.

Animafest’s retrospective featured not only directorial efforts from the sixties onwards but also several early-career shorts on which he worked as a designer-animator for the more famed Vatroslav Mimica of the Zagreb clique. The eight films Marks designed for Mimica between 1958 and 1963 are whimsical and playful experiments, greatly benefiting from Marks’ unconventional background and character designs. During these formative collaborations with Mimica, Vukotić and Nikola Kostelac – Marks co-directed 'Little Red Riding Hood' (1954) by Kostelac, the first color cartoon made in Yugoslavia – he developed a style distinct from prevailing trends both in Disney and the Zagreb School.

Part of what distinguished Marks’ oeuvre – and especially his later work – is his empathy towards alienated individuals. His shorts feature impotent einzelgängers (loners) visibly agonized by their allegorical surroundings. Yet, throughout his career, Marks dexterously switched moods, color palettes, and themes. From the tale of an enthusiastic anthropomorphized and trying to fit in (1966’s 'The Kind-Hearted Ant') all the way up to animations about disillusioned men failing to juggle anxiety, addiction, and loneliness, Marks always approached his stories and themes – however dark – with a light-hearted spirit.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in 'The Undertaker' (1979), a cheerfully nihilistic, 10-minute descent into the daily routine of its titular character, which is interrupted by his fantasies. Bookended by the dull yet menacing sound of a saw periodically going through the wood of a coffin, this grim parable is emblematic of Marks’ filmography. Serving as a Charon for the dead, the undertaker is marginalized; social prejudices condemn him (and his off-screen wife) to a life of solitude. In a last attempt to (re)gain some human warmth, he invites his former customers – the dead – to visit, and they arrive, joining him in a jolly dance to celebrate life and togetherness. But these phantasmagorical appearances are fleeting substitutes for real connection, and the undertaker ends up alone again, with Marks’ angular shapes and simplistic backgrounds adding to the emptiness of the society he seeks to accuse.

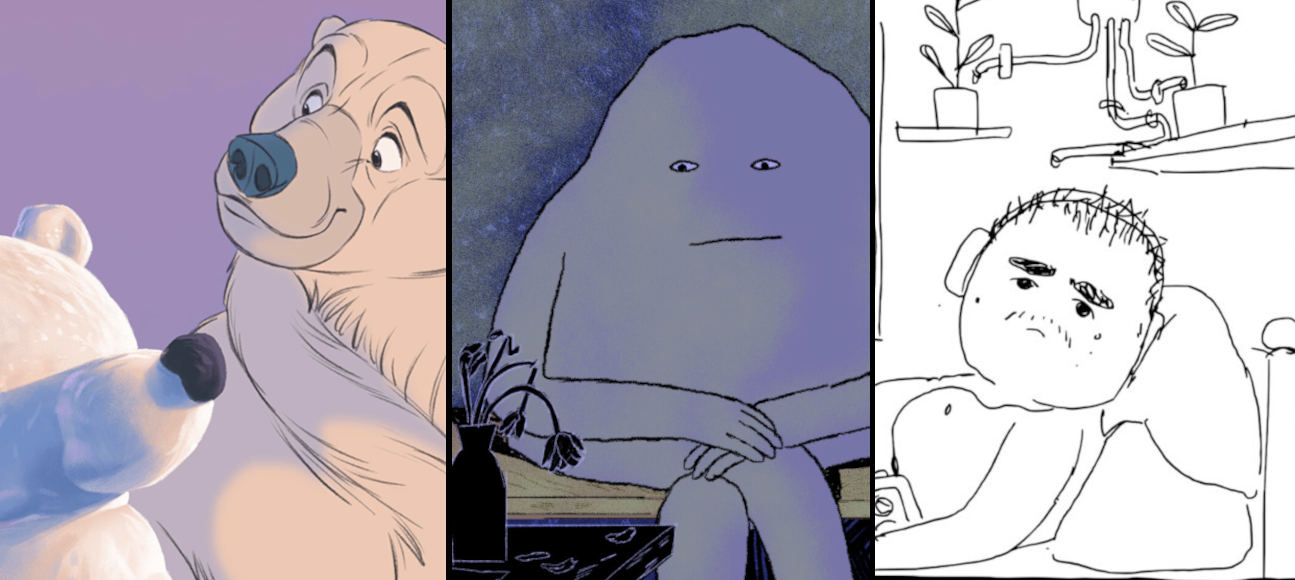

Equally distressing are 'Obsession' (1983) and 'Nightmare' (1976), both stygian tales about mankind’s darkened morality. Loosely based on Edgar Allan Poe’s 'The Black Cat', 'Obsession' is visually reminiscent of a film noir, with an alcoholic protagonist who could easily have been teleported across from a Billy Wilder classic. Marks orchestrates a tormented fight against addiction, but still manages to be playful: here, alcoholism takes the form of a cute little cat that has shapeshifted from a bottle of wine. Poe’s story implies that all evil comes from man, but Marks has the bottle cat as the personification of evil, chasing the man, who eventually defeats it. Still, the film ends in disillusionment: the man arrives home to find this very same bottle on his dinner table.

Obsession by Aleksandar Marks

Obsession by Aleksandar Marks

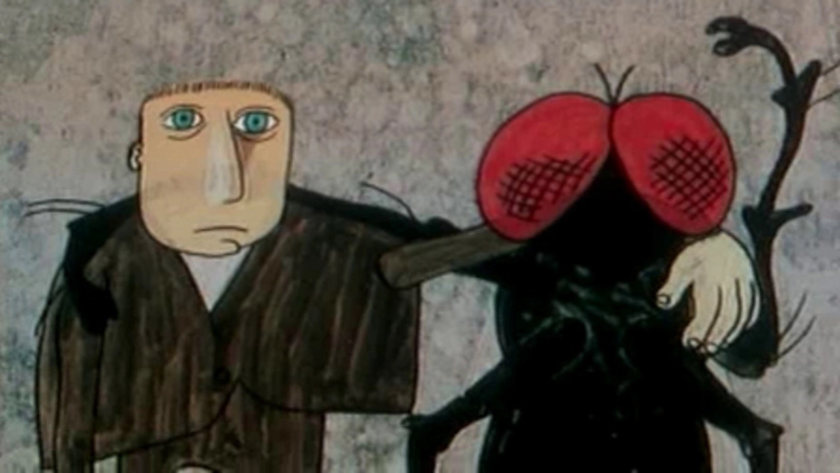

'The Fly' (Muha, 1966) is short with no connection to Cronenberg’s transgressive horror film of the same name. But the latter’s tagline "Be afraid. Be very afraid" does apply. Conjuring up a waking nightmare, 'The Fly' has a minimalist design – referred to as ‘limited animation’- but speaks eloquently to mankind’s fears and the benefits of compromise. When a man tramples a fly, it grows bigger and bigger, eventually becoming his superior in power and intelligence, and to co-exist, the man and the fly must agree. Whether Marks intended to promote egalitarianism, symbolize a utopian vision of total balance or was simply looking to tell another story about isolated men, 'The Fly' was a significant leap forward for his career, and for the opening-up of the Zagreb School to horror elements.

Taking advantage of Marks’s incredible range of projects, Animafest also screened 'The White Avenger' (1962), an entry in Vukotić’s 'Cowboy Jimmy' series which is a spoof on the Hollywood western. Although 'The White Avenger' suffers from rather stereotypical character designs, the short continued its predecessor’s aim of satirizing Hollywood heroes, undermining their inclination to save the day and get the girl. With 'Looney Tunes'-like set pieces, the parody seems a far cry from 'The Fly', though it, too, features his trademark, cynical male characters.

The retrospective closed with two highly innovative shorts by Mimica for which Marks did the animation and character design: 'The Inspector Returned Home' (1959) and 'At the Photographer’s' (1959). The first, in particular, is a feast for the eyes and gave life to one of the Zagreb School’s most beloved characters: Inspektor Maska. Mimica’s dizzying fable about a bumbling police inspector is a radical example of ‘limited’ or ‘reduced’ animation and highlights just how abstract animation can become whilst remaining accessible and entertaining.

The Undertaker by Aleksandar Marks

The Undertaker by Aleksandar Marks

Backgrounds, rooms, windows, and whole interiors are endlessly manipulated to distort perspective, space, and depth. References to the archetype of the hard-boiled Hollywood detective are plentiful, though Marks wittily spins a twist by designing the Inspektor as an annoyed bureaucrat, wearing glasses and a little doodled hat. In essence, Inspektor Maska is yet another of Marks’ isolated men, physically and emotionally detached from the world around them. The life seems to have been sucked out of so many of his characters. Some valiantly fight back, and many deserve redemption, including Aleksandar Marks himself.

Contributed by: Sven Hollebeke