"If You Add One More Word, You'll End up in Hell": Interview with Andreas Hykade

German animation artist /filmmaker Andreas Hykade is a well-known name the festival world, and his influence among emerging filmmakers seems to grow as the years go by. As his CV mentions, "he was born during the summer of love in the Bavarian town of Altötting, “the Lourdes of Germany,” famous for its chapel housing a popular shrine to the Virgin Mary".

It is this chapel that Hykade chose to make a film about, after all those years -and films like We Lived in Grass (1995), Ring of Fire (2000), The Runt (2006), Love & Theft (2010), and Nuggets (2015).

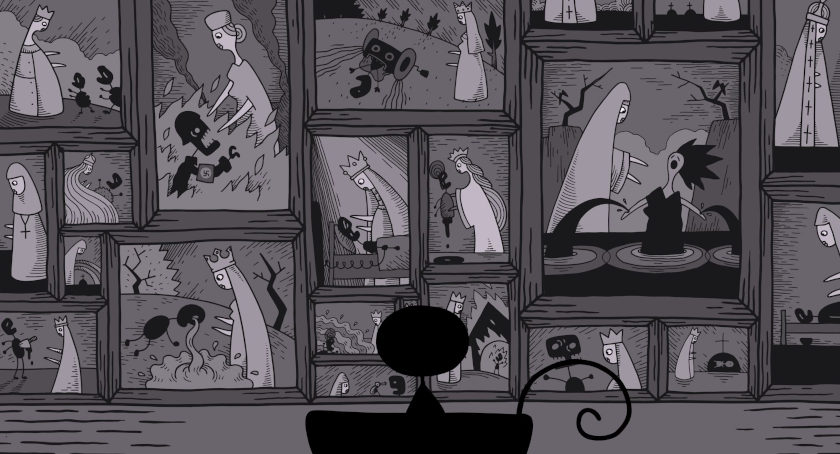

A co-production between Studio Film Bilder, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and Ciclope Filmes, Altötting is an intimate film without in the least evoking intimacy.

Watch the trailer for Altötting:

We had Andreas Hykade talk to us, some time before the online premiere of his film at Annecy Festival.

ZF: How do you feel about making this film? I think you started in 2015, around five years ago.

AH: It's difficult to pin down when one started. Usually this stuff has to sink in for 20 years before it can be expressed. But then comes a time when you seem to be ready, and that's usually where the Allies come in. I think it started with Mark Bertrand from the National Film Board of Canada. We talked about my desire to do a film about my experience with a Virgin Mary. And I'd found out that Montreal (where the NFB is based) is strongly connected with the Virgin Mary cult as well. So there was a natural connection. Another thing was the confidence of the German producer Thomas Meyer-Hermann (Studio Bilder). I've worked with him for around 30 years. And once he's convinced with a subject, I usually know I'm ready to execute it. A third thing to mention here was that the project needed a certain queen to realize the film about the Virgin Mary; and when the subject was ready, I immediately spotted Portuguese artist and animation filmmaker Regina Pessoa. She has exactly these qualities the film needed.

She gave the film the Holy Virgin Mary scoop. At first, we weren't able to raise the budget to bring Regina to Germany. But then the whole thing was strengthened when Regina's partner and producer Abi Feijo (Ciclope Filmes) joined us; he was able to secure the financing for this holy Pessoa Virgin Mary scoop in Portugal. So, we were not only able to include Regina, but also Regina's team that worked on a really high level.

Finally, the sound was done in Canada and I had the possibility to work with great people. One is Daniel Scott, the composer, andthe other is Olivier Calvert in sound design. And we had tenor Bernard Richter, singing this haunting song in the very end. So, all in all, I cannot be more grateful.

ZF: How did NFB find you? Who made the first move?

AH: I made the first move. It's a personal film. If you look at international co-productions, they're usually money-driven. But this project for me is like a healthy alternative, because it was driven by the arts, and driven by the content. That's why this is not only a satisfying experience, but also a model for future projects; to head towards international production, where the need goes beyond the financing.

ZF: What was Regina Pessoa's exact contribution. She's credited as artistic director in the film.

AH: I'll try to be a little more specific. I designed the Virgin Mary parts with Regina in mind (Regina was involved in the Virgin Mary part; the line drawings in the rest of the film it's my little simple style). We proceeded into an artistic, you might call it, response and dialogue. I would do a line drawing and she would do the specific design or a scratchy design; we would then discuss the key drawings until they are ready, and the pipeline she needed to do her work. So, once I knew the key drawings and knew how to prepare the animation, the animation was done in Germany.

There was a gifted Russian animator, Elena Walf, a highly beautiful artist herself. She's very specific and very detailed, so she could provide the basis for Regina and her team to do the work. The line drawings would then passe over to Portugal; Regina would do the key drawings as well, to ease the path for her artists to do the artwork. And so now, I think we have the feeling we're really diving into some religious virtual reality now.

ZF: The aesthetics (color palette), the character design, also point out towards your earlier films, a connection I find immediate and prominent.

AE: You see I started reading Balzac, different bits and pieces, like the short piece Ursule Mirouët.

ZF:I know Balzac as the king of long novels.

AH: it's not true. Individual pieces of work are connected and crafted. You have different novels, but also an overall concept for these novels. That's why people get the impression that things are very long because their characters are popping in and out through the narratives that are familiar to you. I was impressed by that artistic concept. I wanted to do not only a film about religion, but also connect parts of my work together, so that an overall concept could come to bloom. For example, when this guy of Altötting walks out of that film, he walks straight into another film that's been done 20 years ago, called Ring of Fire (2000). It is connected.

That's also a connection with the film The Runt (2006), a film about a boy killing a rabbit. In a way, it's almost like the film Altötting is building a bridge between the character of The Runt and the guy from Ring of Fire. There are also references to a very early student film I've done called We Lived In Grass (1995). For example, this weird preacher out of Altötting, comes from there. So there's a need for the film to be both individual and craft a personal story with a collective appeal. And it's about connecting things to each other; in the end, they should all be consistent.

ZF: Why did you actually choose to narrate your film yourself?

AH: Because I'm now ready for it.

ZF: There's one sentence in your film We Lived in Grass. It says something like" all women are whores and men are soldiers. Am I right?

AE: You're right, but you have to put this sentence in quotes. "'All women are whores and all men are soldiers' my father said' - it's the line. It's not to be confused with the narrator of the film, and certainly not to be confused with the filmmaker.

ZF: But you certainly explore in your work the old dipole of Madonna vs. whore; it seems that you started with the 'whore' depiction, and you now go full circle with the "Madonna' term. What is Virgin Mary to you?

AH: First I have to comment that I don't think it's gone full circle. It's more like the end of a chapter, leaving the virtual Madonna behind, and heading out for real people. I think that's important. It's not a cycle, it's a development and it's probably the end of a chapter. Now, Virgin Mary is a kind of love-giving goddess that I was very happy to be surrounded by as a child, and as a boy and as a young man. And part of this attraction was that the Virgin Mary chapel was the only attraction around. That was in the 70s in the Bavarian countryside, the place I grew up, so you had nothing.

It's 20km from Braunau am Inn, where Hitler was born; it's like 20 km from Marktl, where Pope Benedict XVI was born. And that was the cultural range we had. This limited space is basically defined by old men. So the Virgin Mary seemed to be an alternative; I later found out she is just created by the same old man.

ZF: Talking about creation, was every part of your film created in your mind at the same time or perhaps you had bits and pieces that you added later on?

AH: I can tell you something. I have a very special way of executing films now that nobody practices anymore. The first part is quite common. I do the animatic until it's finished; and it's always based on a certain rhythm. This is the stage where the different versions of the film lie -where the film is in progress. Once it's decided that the animatic is finished, the whole film is ready. It's ready in my mind, and I fill in the exposure sheet, the X-Sheet (the dope sheet, as they used to call it). I write every frame of the X-sheet before we start animating the film. So it's almost like a musical sheet, and the complete composition is finished before the film is done. This is how Altötting was done. Every frame was defined before the film was executed. Every drawing had a number, that's the German part of the film's story making process.

ZF: Seeing and observing all this meticulous effort you put in the film (to be watched as a world premiere at Annecy Festival), I would like to know if you care about the audience reaction and reception.

AE: I don't know. The public is not one thing, it is very diversified. First of all, more than 95% of the world population is not interested in that stuff anyhow. That's to start with. So you're left with 5%, and I hope it will have some resonance on them. I personally like the film. I've seen it now since it's been finished. It will do the job for me. So I can only hope it resonates with the audience as well, and I hope it can become a relevant film about the loss of religion.

ZF: What makes you especially proud about this film?

AE: I think pride is described as one of the seven deadly sins, so I try to stay away from that feeling. I like to try to go with the Zen saying that goes "Before Enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After Enlightenment, chop wood, carry water". And I think that's a humble way to craft your work. And pride can only get between the real nature of art and yourself.

ZF: But would you actually screen your film in your hometown or you don't care?

AH: I'll tell you a funny story. It just happened a couple of days ago. In this little hometown I grew up they had a virgin Mary film from the 50s. A black and white film called Marienfilm by Anton Kutter. I watched that film as a child, and it was part of my inspiration. Now a week ago, the head of the Deutsche Film- und Medienbewertung (FBW), an institute that gives an official stamp to the quality of the films, Adrian Kutter, contacted me because he's been in a jury; he wrote me an email about his father who did this first Virgin Mary film. And I thought, that's a very interesting story. So in my fantasy, I'd like to go back and do a double screening of both films, the 1951 and the 2021 one.

ZF: Probably at a drive-in cinema.

AE: The problem is that in Altötting they don't have a proper cinema anymore.

ZF: Which takes me to the next question. How do you feel about this online version of all festivals? Some people think it's some opportunity for films to reach a bigger audience.

AH: I have very ambiguous feelings about that.

ZF: But your films are online at the Filmbilder YouTube Channel.

AH: After a while. I always keep them fresh for the festivals. I always keep them exclusive for the festivals, because I like the cinema experience, right? I've always waited a year or two, to keep them exclusive for the festivals. And now I see with some worries that the festivals see that as an opportunity to create a new range and setup; they don't see that they have already quit part of an unspoken contract that was defined between them and the filmmakers. This fact should be very strongly considered in further developments.

If I put my film on YouTube at a certain point, I'll get abot 0.1 cents per click; I do not get a cent if it goes to a festival. In the end, we have to make a living from the art that we craft; it should not be just a hobby. Being online was one of the vital fields where a filmmaker could make a buck. And one should take care that the festivals don't become like a natural opponent in this whole game; festivals should support the artists. They should all make statutes where they define how they support the artists; when the film was shown at a festival, they invite the artists, pay the hotel, and they provide a stage for them. What is the deal now with the online thing? This is a question that has to be answered.

ZF: You say that animation is an art and a craft. How do you feel this craft be communicated to the younger generation? You're now (since 2015) the head of the AnimationsInstituut at Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg. What's your impression about the younger generation now doing animation?

AH: I think there's something going on and I don't know what it is. And I better not block the doorways and stand in their ways. But I'll see it as my duty to ask some relevant questions that are thousands and thousands of years old. And in those terms, I try to lead a vital conversation with the young ones.

ZF: Do you find them more secure or more insecure than you yourself were at their age?

AH: It is very difficult to reflect on what I used to be 30 years ago. I was then pretending to be secure, but I was really very, very insecure. To find out that these insecurities are the heart of what you need to craft your work, that was a process I needed to learn. And it's a process I'd like to pass on to the young ones. It's been a constant thing for 20 years since I started teaching; insecurity and vulnerability is the key to the door in crafting certain kinds of work. They don't necessarily help in the second part, when it comes to executing it; but in the first part when you create the basic idea of your film.

ZF: I remember reading a piece (it was a long time ago) that you were supposed to make a feature animation film about the life of Jesus. Would that apply to your definition of insecurity? Feature animation is by its nature a very insecure project.

AH: I don't know about this whole feature thing anymore. Every male animation filmmaker that's 30 years old with a pair of balls says I'm going to do a feature film. And I did the same thing. I'm more humble now. But I have to confess, I'm still thinking about that subject. And there's a certain narrative lying around, with a good ending. And you should never waste a good ending. Still haunting me.

ZF: The Bible has a very nice ending because Jesus dies, but he's resurrected. What better ending could you have?

AH: No, you're not specific. That's not the ending of the Bible. You're quoting the end of the Jesus story. But the end of the Bible is the Apocalypse: where the author says (22:18) "If you add one more word to that, you'll end up in hell". And it's a very nasty ending. So one should read the Bible as a collection of books with different attempts to that; even the Four Gospels of Jesus are completely different attempts.

ZF: So, would you call Love and Theft your first attempt to go to the Apocalypse?

AH: No, that was a completely different cup of tea. I usually try to make personal films, but I got tired of doing that at a certain moment. I wanted to do a film that excludes myself, and only puts in other stuff; mix it about, and be playful and more abstract. A film more about inspiration and expression. It was never planned as a film. When I did this children's series, called Tom and the Slice of bread with Strawberry jam and Honey, I was not able to animate for a while. And I would sneak into the studio in the evenings afterwards, and just animate little cycles. After a while, there were so many of them that I chopped them all together, and called them a film.

ZF: That's good chopping. So, how would it be your own version of Jesus or the Apocalypse? Do you want to tell us at the moment?

AH: It's not possible to tell you because the future is unwritten.

ZF: Since we live at the present, I remember watching an interview of you to Olga Bobrowska during Animateka 2014 festival; you there said you were writing the script for your funeral. Is that true?

AH: That's true. My funeral will be hosted by a character called myself. And myself is doing some lecturing at the moment. It's called Myself's online animation mentoring. You have lesson one and lesson two online. You can watch them and participate and pass it on to the young generations of animation filmmakers.

ZF: I'll do that. Thanks for the interview.

AH: Take care.

Altötting by Andreas Hykade will have its online world premiere during the (online) Annecy Festival, 15-30 June 2020. It has already been selected for the 2020 fall edition of Animafest Zagreb, with many festivals to follow afterwards.