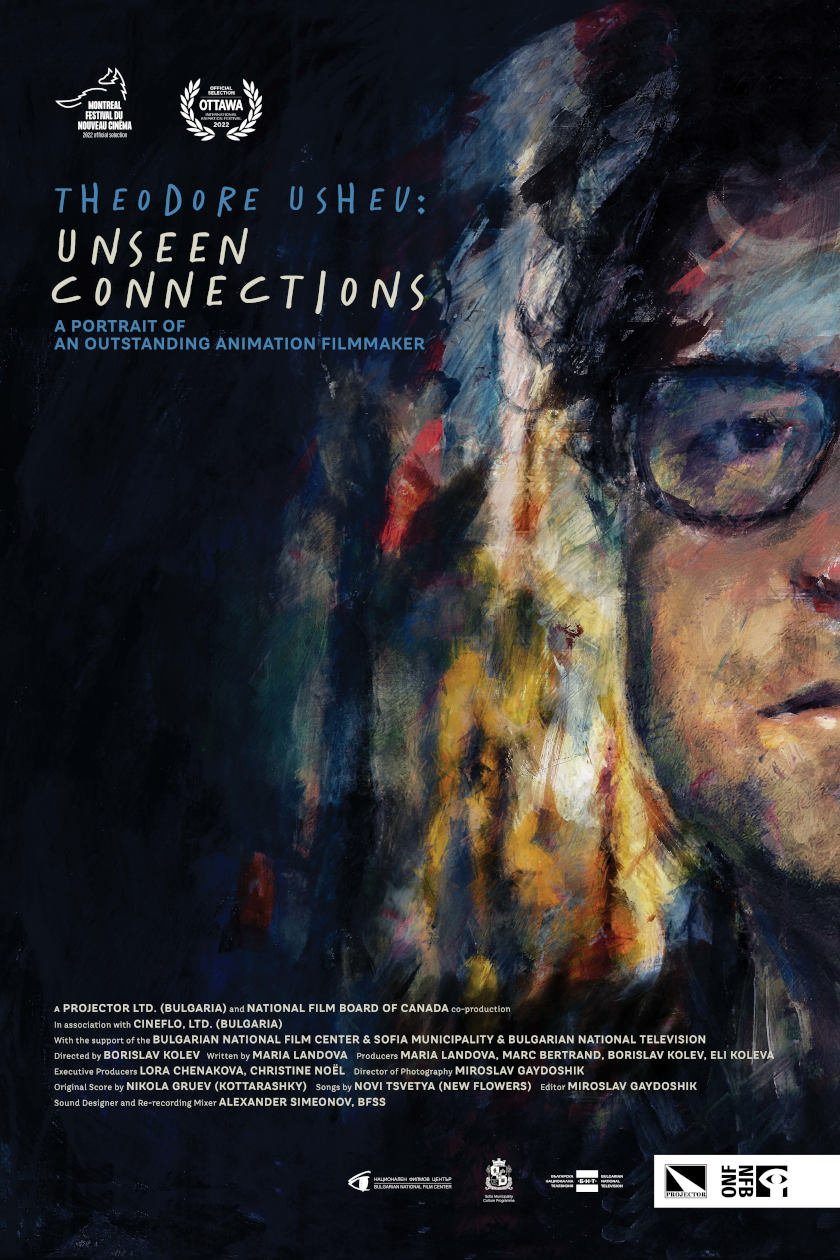

'There's Always Conflict and Dichotomy': Interview with Theodore Ushev on 'Unseen Connections'

This week, Joseph Norman interviews Theodore Ushev, ahead of the world premiere of the documentary 'Theodore Ushev: Unseen Connections' (director: Borislav Kolev), at Ottawa International Animation Festival, Canada, 21-25.09.2022.

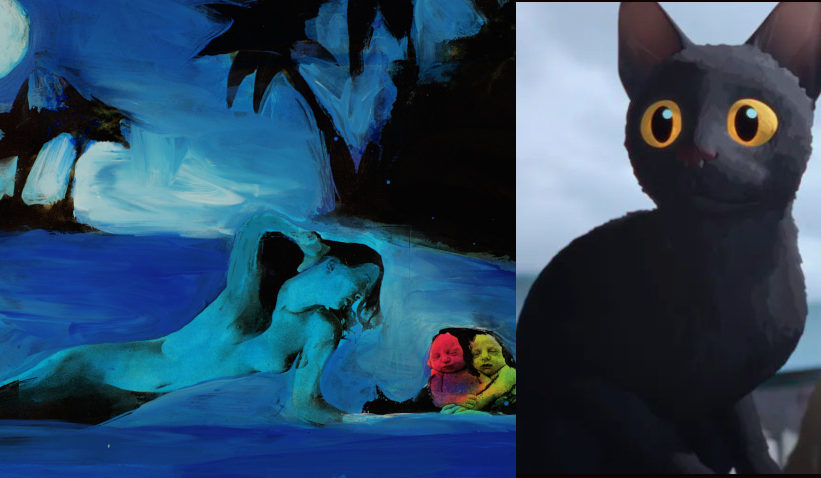

This poetic documentary takes an emotional journey through space and time, exploring the origin of themes that drive Ushev’s animated and live-action films. In an engaging and very interesting conversation ranging from his formative years with punk music as radical energy for change, to the relentless urge for artistic freedom, Theodore opened up about his creative process and how his haunting and enigmatic films take shape.

We talked to Theodore Ushev (via videocall) in Sofia, Bulgaria.

ZF: How long was the documentary production?

TU: Actually, I was shooting my first Live Action film, when the director came and said, “Listen, I want to do a documentary about you. Using some footage and you can assist in places where you should”. And for about two weeks, he was following me around Bulgaria. And there was some shooting in Montreal that he couldn't provide because of the COVID situation. But we found someone else to shoot the little detail, some small videos in Montreal.

ZF: Were you very involved in the post-production?

TU: Not at all. I haven't seen the final film because it's a film by the director. I wouldn't want to interfere in any way with how he sees me. I don't want to see the film anymore because I don't like watching myself on the screen. I'm an animation filmmaker… I like to paint and draw and make films. And I said listen, you see what you see and that's it. You can make a view of me if you want, you can make me a monster, but it is your vision, if this is how you see me, so that's me. So, it was not a too creative output from my side. I was talking only about my films and my creative process and everything that built me as an artist and that's it.

Watch the trailer for Unseen Connections

ZF: Did you know the filmmaker prior in any way?

TU: No. I had heard about him. I knew that he did some documentaries about famous Bulgarians. He's really specialized in documentary films that is what he loves to do. Also, he did many rock films for rock bands in the 80s and 90s. So, what is interesting is that he didn't know almost anything about animation. He's not involved in the animation circles. So, he was not watching me as an animation director, but mostly as a person and everything else. He used to be one of the most famous film critics in Bulgaria.

ZF: And with the punk band the New Flowers, which obviously were very prominent in the film, and it seemed to me, obviously, the kind of the punk ethos seems to have been a major part of growing up, your culture, and your identity. Were you part of the group or you were just friends with them when you were young?

TU: I was friends with the guy who formed them since we were kids. Because my father and his mother were very close friends and when they were visiting them, and in the evening, when they were drinking and chatting, we were drawing, making comic books together. So, no, I didn't play with him, but I drew with him. So, that's what we were doing. He was very good; he was better than me as an artist. He just didn't want to become an artist, he preferred being a musician.

And at the time, they had like a huge problem with the Bulgarian Communist militia. That was how they were called – the police. Because they were playing music which was forbidden, absolutely forbidden there. And almost every week, they were taken and put into the police for one night and interrogated. And it was a very difficult period for him. And even with this, he continued to make his art. But he was really like a real rebel. It's pure art, a brut art, out of the marginal, the purest punk that ever existed in Bulgaria, was him. He never wanted to be established, never wanted to make money from the music, he was always making his songs for the love of music and from the love of self-expression. And mostly for the love of being rebellious, against everything.

ZF: That sounds to me like a shared ethos in your work coming from the same background.

TU: Yeah. I guess that's why the director made this connection. What is interesting is that I was using their music in my live action film, ‘Phi 1.618’, that I just finished, which is going to play as well in almost every festival that plays the documentary.

ZF: What was the experience like of working with live action in contrast with your more well-established animation process?

TU: I love it. Actually, there are eight minutes of animation in my live-action film. So, I couldn't resist putting in some animation. Because it changes everything: the perspective is different. I loved it because as an animation director, I thought about all I do is animatics and I can imagine every single scene, and I was drawing them on my storyboard and it was so precise, that it was very easy for all the production crew to follow my direction. So, that's why the film was cheap to make, we did it for very little money. And only 23 days of shooting for my Live Action film.

All the stories were painted on the storyboard. And the way I was working with actors is what brought me to Live Action. I loved the creative output and I think we just got the news that we got financing for my second Live Action feature-length film. But I'm also in the production of two animated short films. Live Action takes years of waiting for financing and pre-production that can kill you if you're just waiting. So, between waiting for all those things happening, I do my animation films.

ZF: In the documentary, your Mum said to you that she thought that the way that you operated as an artist was very surrealist. And you felt, in fact, that it was social realism. How do you approach the conflict between the two?

TU: Yeah, in my films, there's always this conflict and dichotomy. It’s like a cognitive dissonance between social realism and surrealism. Surrealism was my escape from social reality which existed, it was very bold, and you couldn't escape it. It was just putting your hand and hanging you to the system and to the wall, and you couldn't move. So, the only way to escape was dreaming, and dreaming about something, inventing. I say very often that I became an animator because I always dreamed. I used my imagination; it was a kind of escapism from reality. I don't like social realism in cinema because everything that is realistic reminds me of my background and of my childhood. I didn't feel free. It reminds me of prison.

ZF: In the film, you describe how you were once hired by a major Hollywood production with a big director, to do some animation within a film for them. And in the end, you walked away from the film. You said you felt like you were being strangled. What you needed above everything else as an artist was freedom.

TU: Yeah, I just couldn't do it. I prefer to stay independent and to work on my own films and do my own mistakes than to follow someone else’s patterns. It was just not for me.

ZF: There's a very strong sense of a journey through time and space in 'Unseen Connections'. Obviously, you're physically on a journey, you're going back and you're visiting your mom, you're visiting your childhood friends. And it seems to me that in your trajectory as an artist, and in your animated films, there often seems to be a sense of a journey and forming. And that also informs your technical process of the rubbing out and over painting and stuff. How does that work for you when you're creating?

TU: The director of the film said, I'm going to build the film around 'The Physics of Sorrow'; it is pretty much biographical, I mixed some stories from the writer of the book and my personal stories and the stories of friends of mine from that time. He used that structure, especially about the journeys, about traveling between time and spaces and different continents, because this is what describes me, I'm always in a constant movement between two continents, Europe, and North America. And it's not easy. It's like your spirit is always seven hours away from you. You know, the Bedouins when they travel in the desert, sometimes they stop so their soul can reach them. So, yeah, it was like, waiting for my soul to reach me where I am.

The Physics of Sorrow

ZF: In your installation, ‘In the Mirror, Dimly’, you wander through Sofia, using the invisible ink to draw and write secret messages on objects that can only be seen with UV light. And in 'The Physics of Sorrow', you treat objects, such as a gum wrapper, as memory triggers. How do you select the objects to write upon?

TU: It's always about stories. When you take an object out of its story, it becomes something else. It's the same with the city, the same with the objects, we are all objects. Every object that you displace from the place where it belongs, becomes something else. You try to keep the stories, but it becomes something else. And this is what interests me, it's never the same, it changes, (like) in 'The Physics of Sorrow ', when you move to another country, no one pronounces your name as your mother pronounced it when you were a child.

ZF: How has living in Montreal, compared to where you grew up, affected your output and your ideas?

TU: When I moved to Montreal, I felt very free. I felt like I found my place. Because of the people who I worked with, because of the National Film Board of Canada, where I found my place to develop as an artist, and as a movie director. I never studied filmmaking. I've learned the ABC of filmmaking at the National Film Board of Canada. For 16 years I had my studio at the NFB, and it really helped me to develop as an artist. My producer Marc Bertrand, who worked with me, was really giving me everything that I needed to develop myself, he was really like my father. My father was far away and I found my father there in Montreal.

The most important people who really built my personality are not in the film It is my wife or my producer or my daughter, she was very important to me, because at some point she started teaching me. Now she's 21 and she studies cinema, and she helps me enormously. My father because he was dead already. My sister, passed away recently, only two months ago. Or my grandfather who taught me languages through comic books.

ZF: Thanks Theodore. This has been a highly interesting discussion, and very stimulating to hear so candidly how the stories have taken shape, and to understand the roots of the ideas and creative process. We will look forward to seeing Theodore Ushev’s upcoming live-action film, ‘Phi 1.618’ on its release.

contributed by: Joseph Norman

'Unseen Connections' by Borislav Kolev has its world premiere at the 2022 Ottawa International Animation Festival, 21-25 September 2022.