The Phenomenology of Perception: Interview with 'Kafka. In Love' director Zane Oborenko

We first wrote about Zane Oborenko and her project 'Kafka.In Love' during the CEE Animation Forum 2019, where it won the first prize for a short animation project. The Latvian animation artist, who studied at the Estonian Academy of Arts -under Priit and Olga Pärn, has been developing and producing (at Atom Art production company) the new animation film, with her distinct use of sand animation. Her previous, student film ‘IMG_00:01.JPG’ (2013) received the Best Student Film award at the Fredrikstad Animation Festival. Her very new film, ‘Hope’ will premiere in the cinema at the Riga International Film Festival. So, it looks like a busy period (despite the pandemic) for Zane Oborenko.

(Update 10/11/2024: The film is now co-produced with Czech company MAUR Film).

The story of 'Kafka in Love' refers to, in a very non-narrative, empathetic way, to the celebrated author’s love letters to Milena Jesenska; she was a Czech journalist married to the Jewish intellectual Ernst Pollak ('Actually, it was Ernst Pollak who apparently introduced Kafka to Milena’, Oborenko says). It is a long-distance relationship (sounds familiar in our times?) from 1919 to 1923, which became a passionate epistolary love. In Oborenko’s version, the whole thing will be presented with the sand animation technique, after conducting a video reference shoot with actors. But why is Kafka being the subject for a Latvian artist? ‘Kafka, his literary works and especially the notion - Kafkaesque - has entered our subconscious mind’, she replies, ‘I guess he belongs to everybody. In our daily lives we deal with so many Kafkaesque situations especially when facing certain systems and institutions; and recognizing them as such somehow has ability to give a certain relief of not feeling completely bewildered and alienated by such experience’. As she herself was studying in Italy at that point (her B.A. degree was in painting in Milan Academy of Arts -Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera), these aspects of long- distance relationships (family, friends, her future husband) certainly influenced her perspective on the film itself.

But why is Kafka being the subject for a Latvian artist? ‘Kafka, his literary works and especially the notion - Kafkaesque - has entered our subconscious mind’, she replies, ‘I guess he belongs to everybody. In our daily lives we deal with so many Kafkaesque situations especially when facing certain systems and institutions; and recognizing them as such somehow has ability to give a certain relief of not feeling completely bewildered and alienated by such experience’. As she herself was studying in Italy at that point (her B.A. degree was in painting in Milan Academy of Arts -Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera), these aspects of long- distance relationships (family, friends, her future husband) certainly influenced her perspective on the film itself.

Yet the inspiration for ‘Kafka In Love’ came after her M.A. Degree in Tallinn. ‘The National Film Center of Latvia opened up a new call for new directors who have never made a professional film before. And so that was an impulse’, she tells Zippy Frames. Both Sabine Andersone and Edmunds Jansons from Atom Art told her to jump on the wagon and apply. ‘That was the first very active moment of thinking about what this film could be. I stumbled on Kafka’s letters to Milena, and it seemed that this somehow could work as a film’.

A lot of research followed, with letter reading, books, and internet research. ‘It was a very, very difficult process to condense it into a short animated film.’ Milena Jesenska had her own dramatic life: she had a difficult relationship with her husband and father, and in her early teens she would experiment with opiates (her father was a dentist) after her mother’s premature death. At the same time, she was a staunch supporter of human rights; she joined the underground resistance movement in Prague, and finally died at a Nazi concentration camp as a ‘Jew supporter’).

'The relationship between Milena and Kafka was not easy', Oborenko attests. Kafka was already engaged at that point, and trying to move to a new place with his fiancé, but clearly having an affection for Milena; on the other hand, Milena was torn emotionally between Kafka and her husband. 'She knew that Max Brod was Kafka’s best friend [and, ultimately, his biographer]; at times, when she was worried about him or how he's actually doing and feeling, she would write to Max Brod and ask him about Kafka'.

Kafka and Milena met physically only twice during their letter writing period, and when the relationship ended she would write occasionally to Max Brod as well. This letter exchange looks like our pandemic situation – but there was also something more urgent. 'It was a postwar period, there was a shortage of supplies and food and she as a foreigner felt alienated in Vienna. So, Milena would ask Kafka sometimes to go to her father and talk to him to ask for some money and help with food and other mundane affairs; Milena’s husband at certain point refused to give her money as she was spending it too quickly, therefore Milena herself started to work as a check language teacher, as a fashion correspondent for “Tribuna” a periodical in Prague and even as a porter in a train station.'

Watch the trailer for Kafka In Love:

This is a lot of information and material, yet the short film needs to take its own narrative stance. ‘The focus is more on the emotions they felt; short films, and especially the animated films, are trying to express what's inexpressible in words, like those little fleeting, at times magical moments, emotions and inner challenges; we're trying to put these into visual language. It should be a means to open up more interest about Kafka and Milena, and go read their books and stories’. Since Milena’s own letters to Kafka were destroyed, the film concentrates on Kafka’s letters (‘I could access some of the feelings and emotions that he felt through his letters; the story develops from his perspective, and Milena remains more as imagined in his mind, not exactly as she was in real life).

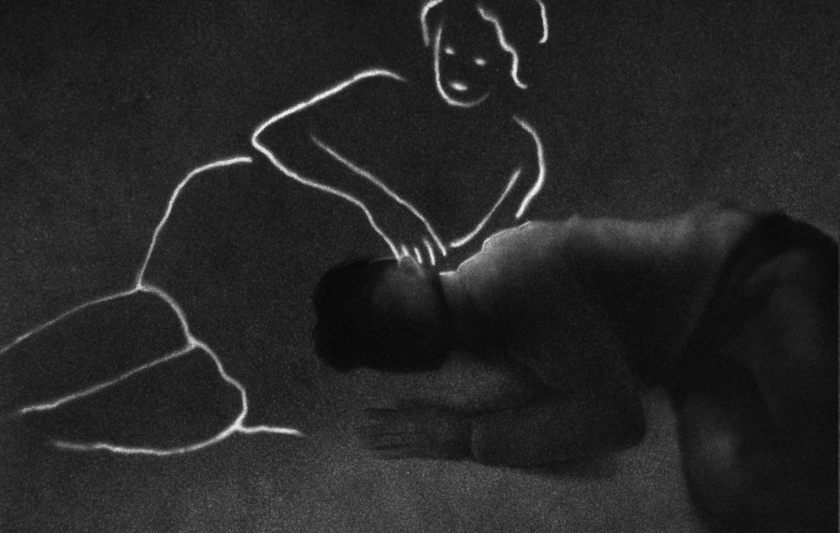

The film process started with a one-day shooting with actors, with Oborenko sometimes using herself as a stand-in (‘in certain places, you can see myself posing in the place of Kafka and in place of Milena -so of course, I'm becoming like them in a way'). She used this to her advantage as her own directorial statement as well: ‘I think that at a basic level our physiological and emotional needs are very similar; hunger, the emotions of love, pain and suffering. I think it’s universal for every human being’.

The video reference helped Oborenko, and she would find a way not to have it look like simple rotoscoping. ‘My task has always been to experiment with the natural movement that's present in nature and human beings, and then to somehow transform it, work upon it and make it different from reality; but I still want to be something that contains the actual natural life movement.’ The Dragonframe software was used to upload the reference video, and then check against this when sand is being animated. ‘When Kafka is putting his head in the imagined Milena’s lap and she's caressing his head, he's kind of melting slowly. This is one example of being more creative than the video reference, and still exploring what else can be done with the sand so as to portray the emotional changes in Kafka’s mind’, she explains.

Oborenko made her student film ‘IMG_00:01.JPG’ in sand animation as well. ‘Before I started doing animation, I had this fascination with graphic styles, and I was making drawings with pencil, ink and etching using mainly small dots; sand just gave me that possibility to exactly do that. It is just much faster, and sand also has this graininess that's pertinent to analog photography and movies that I love. I find that this graininess of sand and analog film can be reminiscent of our own fragility and even our fragmented nature - I mean fragments of our past experiences make of us who we are today.’ The Kafka project proved particularly fit for the purpose. ‘

The idea is that reality is very close to but also distant from the imaginary world. And so the sand allows me to be very realistic at times and not realistic when it's not necessary; Milena’s character in the film starts as a line, and she would slowly form her visual body as seen through Kafka’s imagination full of emotion, a flame and rather ethereal being. But at the very end she becomes photorealistic and it marks a break in their relationship’. This exchange between the inner and the outer, our imaginary interior and our real life compartment still fascinates Oborenko.

The practicalities of working with sand animation are distinctive, and the director needs to use different tools both to animate and move the unnecessary sand away. Physical rules also apply here: ‘I prefer to use different transparent plastic tools and If you rub them against some piece of fabric, it creates an electric field around it, and as you move it close enough to the sand it jumps and clumps together a bit; on the glass surface, it creates a different texture; you cannot get that chaotic and organic looking effect in any other way’.

There are also tools for smoother texture, all sorts of cut-out self-made plastic pieces, different density foam rollers, and even a car vacuum cleaner for sand collection, a very handy but noisy tool adapted for sand animation. 'I learned about it in Tallinn. This tool allows to suck away the sand from parts on the animation surface that otherwise would be difficult to reach or move without destroying everything else around it. Working from home allows me to use it freely without worrying about how disturbing it’s sound would be to the other colleagues in a bigger studio setting'.

Atom Art production manager Ieva Vaickovska could find Zane Oborenko her own batch of sand on Latvian beaches: ‘These old sand layers have the specific size of sand grains that I use in my animation’. Size is important: too big grains are useless for details, and too small again have their own minuses. Oborenko works in layers in her scenes, and so the time to animate a scene varies. A lot of layers slow down the animation, and the other way round. Compositing of layers takes place in After Effects; the director animates mostly herself the whole thing in her studio and place -with one assistant - Līva Piterāne helping to animate a bit easier stuff like flying letters, dust, etc.. ‘I’m experimenting while animating, so I come across many discoveries, and sometimes it’s impossible to explain this to someone else’. Still, the video reference helps delegate certain parts of animation to others -even though the whole project would need definite dedication from the side of the animators.

For an animation director who started her training as a high school art student (Janis Rozentāls Riga Art School), and continued her education (one year) in the Art Academy of Latvia - Restoration and Conservation Department, followed by a BA degree in Painting at Αcademy of Fine Arts of Brera (Milan, Italy), this art education really helped her a lot. She learned to be precise, clean and not ruin a work of art - just like her own work of art in the making.

Her 137,000 EUR budgeted short is an Atom Art production effort (‘if they say that they can do something, usually it is done’). Pandemic considerations also taken into account, the film started when Oborenko’s own son was 2 ½ years old (he’s now six years old and wants to experiment with sand animation as well), and it helped for the director to put her studio in her own place (‘just setting up a corner at home’).

Pandemic also gave the director time to complete another poetic film, ‘The Hope’, now travelling to festivals, including Riga International Film Festival. The film is described as ‘a visual meditation on the essence of hope’, and you can feel the same sense of developing and growing that Oborenko describes for her Kafka film. ‘18 months ago, I was approached via email by Evgenia Gostrer, the curator of a special program focusing on Baltic / Eastern European countries at the Festival of Animation Berlin (FAB); she asked me if I had something to show her. And I had this sand film with leaves that I wasn't considering as anything particularly interesting to anyone else but me. And her wish to include it in her festival came as a very pleasant surprise.'

The film itself was created from recycled animation; Zane Oborenko made these leaves for the Latvians Abroad Museum and Research Center. The museum approached me to make animated videos on different objects people chose to take with them when escaping Latvia in their collection since they were planning an exhibition. And there was a story about a Latvian Baptists escaping to Brazil. I was animating a scene where trees in the jungle are cut down and their leaves are falling off. So, in a sense, the leaves were already animated; I just rearranged them in a different composition to a different music’.

Edgars Kārklis was the composer of the ethereal 'Hope' score; ‘I heard this music, and I imagined that the leaves would fit perfectly to this; I was in this kind of meditative process, observing my thoughts and myself. I intuitively started to add layer upon layer, and see where it ends -the only limiting factor was the existing piece of music and leaves as a main character’. Riga International Film Festival it’s the fifth festival 'Hope' has been accepted (‘it is home’, Oborenko mentions). Is independent animation her own home as well? ‘I consider myself as an outsider in this Latvian animation scene’ she confesses, ‘yet Atom Art has been a link to others working in it. The (now late) puppet animator Nils Skapans was one of her acquaintances, as well as Gints Zilbalodis and the producer of the recent Annecy-screened film ‘Panic’ by Elina Malagina, Reinis Kalnaellis (both met during Riga IFF). Oborenko is now also a member of the Latvian Animation Association.

Her favorites being Koji Yamamura (another Kafka adaptation in the 2007 ‘A Country Doctor’), Caroline Leaf and Yuri Norstein, Oborenko still relies on real stories. ‘I have always been fascinated with real stories; reality often can be much more surprising than things that you invent just like that out of thin air, but then there is plenty of great literature and stories that are both- based in reality and staged in inventive imaginary worlds- that’s definitely a direction worth exploring’.

This puts her into a mood of responsibility with her upcoming ‘Kafka. In love’ film (‘I'm using his name in the title of the film’), yet this won’t diminish her interest in what she describes as ‘the phenomenology of perception that it's very individual to every one of us’. As she states, ‘our life experiences are limited, but when you dive deep in a story and read about somebody else's experience, it's a way of living it somehow. Making an animated film or film out of it, in general, is also a way of going into that space and discovering something that you didn't know before in a different way than it would be just by reading it in a consumerist manner‘.

Her next endeavor would be a more abstract short film, again dealing with emotions. ‘I think we need to rest from something that has been challenging, and I think that's time for an abstraction.

The 10-minute ‘Kafka in Love’ is about to finish by the end of 2022, yet Oborenko is still thinking of a later date (‘I wouldn’t want to limit my imagination and sacrifice the visual effect. I think I will come up with some new ideas on how to simplify and speed up certain things’). In the meantime, ‘Hope’ has its Latvian (on-site, in actual cinema) premiere at Riga IFF (14-24 October). Hope and love is all we need, and fine animation on top of that -and it seems that Zane Oborenko can actually give us all three.

The interview was conducted in partnership with the Latvian Animation Association.

Update (10/11/2024) 'Kafka.In Love' had its world premiere at the Riga International Film Festival 2024, and now travels to the international film festival circuit (PÖFF Shorts, Cinanima Festival0