Grotesque Metamorphosis and Creative Practices in Jan Svankmajer by Irida Zhonga

[The article won the Honorable Mention in the Maureen Furniss Awards 2021 for the Best Student Papers on Animation Media, conferred by the Society for Animation Studies]

INTRODUCTION

Stop motion animation is the method of photographing successive objects or puppets to create the illusion of movement. It is literally the technique where an inanimate object ‘comes to life’. It allows artists to break down the barrier of the human world and create an amalgamation of our physical existence and the otherworldly sphere of the puppets (Thomas & Johnston, 1996, p. 146). Released from the strings that once connected them to their puppet master, these puppets can now escape from their theatrical past and are finally able to walk on their own. They join a metaphysical dimension of reality. Thinking about the gaze and form of stop motion puppets often means to be induced with feelings of uneasiness, horror or amusement. Such responses in viewers are also created by the usage of disproportional and fusion figures as a way to enhance the film’s imaginative narrative, and create an eerie and alienating world. The aforementioned characteristics are key to the aesthetic category of the grotesque which will be the main focus of this paper.

Noel Carroll (2013) describes the grotesque as, a “departure from the ordinary”, whereas Wolfgang Kayser (1963) tries to explain its nature as that of an “estranged world”. The concept of the grotesque is difficult to define concretely; the variety and complexity of this term lies deep, making it more than just an aesthetic category. Its polymorphous strategies can also be used as an instrument of understanding universal laws, harmonies and oppositions. The animated works of pioneering filmmaker Jan Svankmajer have been pivotal when it comes to visual manifestations of hybrid forms and the formation of illusory supernatural life by merging objects of animate and inanimate simulacra. This essay will explore in which ways the grotesque is portrayed in Svankmajer’s films by examining manifestations of grotesque in the bodies of the puppets as well as in the filmmaker’s creative process. When going into a more in depth analysis, I will employ Mikhail Bakhtin (1984) concept of the ‘grotesque body’ and its relationship to the earth as an unfinished metamorphosis of existence (as stated in Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984, p. 303.) Furthermore, Wolfgang Kayser’s writings on the grotesque as an alienated world created through the practices of the artist will also be employed. It will serve to identify how Svankmajer mixes and alters the ‘biological and ontological categories’ of everyday objects (Carroll, 2013, p. 307).

THEORETICAL STUDY OF THE GROTESQUE

Before constructing the theoretical preparatory ground for the investigation of grotesque in stop motion films, it is useful to explore how the term has developed over time. The word ‘grotesque’ was first used in the 15th century to describe a particular style of ornamental frescoes found on the ancient sites of the Roman emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea (Harpham, 2006, p. 23). The name derives from the Greek word Κρύπτη which means cave or vault, and when used as a verb, to hide (Harpham, 2006, p. 27). The term hides a pregnant truth and generates an allusion to the underground, linking it to Bakhtin’s concept of the grotesque body and its connection to earthliness.

This discovery of Nero’s Domus Aurea was one of the most influential of the Renaissance period as on the palace walls, murals of absurd hybrid ‘monsters’ were found that blended themes of human, animal and vegetable forms. Initially created to describe a particular type of visual art, it was soon used to refer to other art forms such as literature, where it was used to describe ‘monstrous’ or ‘freakish’ representations that deviated from classical and harmonious art. The elements that presently make up the grotesque are not limited to the principle of ‘absurd’ entities but rather as summarised by Geoffrey Harpham (2006), “they stand at the margin of consciousness between the known and the unknown, the perceived and the unperceived, calling into question the adequacy of our ways of organising the world, of dividing the continuum of experience into knowable particles” (p. 3). Moreover, the complexity of the grotesque is evident on a theoretical level, and both Wolfgang Kayser and Mikhail Bakhtin will be used to explore the concept and characteristics that I will later apply to the analysis of stop motion animation.

Kayser is one of the most prominent theorists when it comes to the grotesque. In The Grotesque in Art and Literature (Kayser & Weisstein, 1963), he focuses on its evolution in arts and literature from a historical perspective and, most importantly, he attempts to clarify its nature. For Kayser, the grotesque is the amalgamation of the comic and the horrific, it presents itself in paradoxical forms and evokes paradoxical reactions (p. 56). Thus, while Kayser underlines contrast as being fundamental to the grotesque, he also emphasizes its ambiguous nature. He attempts to define it when he states, “the word grotesque applies to three different realms – the creative process, the work of art itself and its reception – is significant and appropriate as an indication that it has the makings of a basic aesthetic category” (p. 180). This three-dimensional feature can be present to any kind of art but it opposes all other types of physically created productions. The unique form of the grotesque works by means of a dichotomy. The object can be perceived either as part of this world or out of the world, and it is predominantly dependent on the audience’s expectations in a certain sociopolitical context. What was considered grotesque to a fifteenth century audience is not necessarily considered grotesque today and vice versa. Kayser';s conception of the grotesque is opposed by theorists who provide ignorant interpretations of the grotesque, which can lead to misunderstanding of the concept (p. 181).

Even though Kayser has a clear focus on matters of reception when it comes to grotesque, he attempts to define its structural features by arguing that “the grotesque is the estranged world” (pp. 181-185). This is a world where what we experience is in a way alienated, and there is a certain confusion and absurdity when it comes to its form. Despite the ambiguity of this world, there are certain motifs and characteristics that have been repetitively observed in grotesque works of art. Some of them include ‘monstrosities’, the merging of organic and mechanical realms, hybrid animal figures and insanity (pp. 181-185). Through the grotesque, inanimate objects become estranged by “being brought to life” whereas human figures are estranged by “being deprived of it” (p. 183). The grotesque has the ability to transform our world and alienate it, since the objects that were once familiar to us have now become strange and ominous. These transgressive features of the grotesque perfectly apply to the stop motion puppet films of the surrealist director Jan Svankmajer, where fusions of biological forms and disruption of ontological categories are evident throughout his oeuvre.

When looking at this alienated world, whose perspective is represented though? Kayser directs us back to the artist and their practice when he says that the “estranged world appears in the vision of the dreamer or daydreamer or in the twilight of the transitional moments” (p. 186). The artist is the “dreamer” who through their practice is able to create such an estranged world by altering the structure of the objects they are using. The creation of grotesque art is a “play with the absurd” and, according to Kayser, this absurdness makes two types of grotesque emerge; the “fantastic” and the “satiric”. For him, laughter resulting from satire is an involuntary response to situations that cannot be dealt with otherwise. It is a reaction to the absurd and a forced attempt to get rid of the fear that comes with it (pp. 186-187). This idea links Kayser’s notion of the grotesque to Bakhtin’s conception of folk culture and the subversive nature of laughter through the inversion of reality.

In his book Rabelais and His World, Mikhail Bakhtin (1984) discusses the meaning of the body and the lower bodily stratum as a subcategory of the grotesque in relation to the literary mode of medieval grotesque realism. The “material bodily principle” plays a predominant role in grotesque realism and is connected to the body’s earthliness, its union with the soil and the its regenerating effects (p. 18). For Bakhtin, the images of the material body have a positive connotation since they are linked to the festive and cosmic aspect of folk culture. This process of directing everything on a downward swing towards the earth manifests a connection to the physical, the “lower stratum of the body” and the processes of “digestion, defecation, copulation, conception, pregnancy, and birth”, which Bakhtin refers to as forms of “degradation” (p. 19). This essential principle of the grotesque is a phenomenon of transformation and metamorphosis where the body is perceived as an open, unfinished unit which is constantly growing, changing and regenerating (p.24). The positive character associated with the bodily is the reason behind the exaggerated and hyperbolised representations of it. The material body is celebrated to its full extent and is portrayed as triumph of everyday people’s existence (p. 19). The festive nature of the grotesque body is a key feature of Bakhtin’s view, and cannot be overstated enough. One can notice that this embodying fluctuation of the grotesque image comes in complete contradiction to the classical aesthetics of the human body.

Bakhtin’s perspective on the grotesque can be better understood when investigating the societal shift on the field of the aesthetics of the period that he is referring to in his writings. When classical aesthetics replaced medieval aesthetics during the Renaissance, the focus shifted towards a complete and ideal body, and away from any traces of its biological function and unfinished nature (p. 24). Any indications of its unfinished character were kept hidden. As a result, the grotesque body, from the point of view of the classic cannon, was perceived formless, monstrous and horrific. This switch in aesthetics led to an eventual estrangement from “the positive pole of grotesque realism” and the folk culture which once empowered the bodily form and brought the world closer to man (p. 53). Mikhail Bakhtin, like Kayser, argues that the essence of the grotesque lies in the monstrous as a result of the transformation the concept underwent during Romanticism. During this period, the main characteristic of the grotesque was “a vivid sense of isolation”. Laughter, the once prominent central feature of grotesque, was now reduced to “irony and sarcasm”, which annihilated its regenerative features (pp. 36-39). If fear cannot be defeated through laughter, then the world of Romantic grotesque becomes a terrifying and alien world (p. 38).

GROTESQUE REPRESENTATIONS IN JAN SVANKMAJER

Stop motion, as already mentioned, is an animation technique by means of which puppets ‘come to life’. One could even argue stop motion animation is a contemporary form of theatrical puppetry, albeit one in which the puppet is liberated from its former constraints and is finally able to move freely through space. However, this freedom is of course merely a visual illusion discovered by accident in 1895 by Alfred Clark. A year later George Méliés used stop motion for the first time to move and give life to inanimate objects, marking 1896 as the birth date of the technique (Gasek, 2012). The manipulation of the cinematographic process transformed reality and granted objects a supernatural dimension. Early examples of grotesque themes are evident in his work, such as A Trip to the Moon (1902). Méliés was one of the first filmmakers to use fusion forms as part of his obscure and surreal narratives (image 1).

Image 1. Méliés, G. (Director). (1902). A trip to the moon [Film]. Pathe.

The inception and development of puppet animation was however mainly associated with Eastern Europe and the Zagreb School in former Yugoslavia. The focus of those animators of this school was on the aesthetic and philosophical aspect of the craft. They emphasized on the creative part of ‘giving life’ to unveil something about the figures and objects that otherwise would not be understood (Holloway, 1987). One of the most prominent and influential surrealist animators of puppets and found objects, Jan Svankmajer, draws attention to the hidden inner life of the found objects he collects and uses in his animated films. He states, “In my films, I move real objects…everyday contact with things which people have touched acquire a new dimension and in this way casts a doubt over reality…I use animation as a means of subversion” (Wells, 1998). These objects have been marked by people’s past actions, they have witnessed certain situations and have been imprinted by their past owners’ mental states. For Svankmajer, bringing life to the objects through animation is a slow and natural process, since for him the objects possess a will of their own. This practice of re-contextualisation of the objects’ identities, breaks the invisible ontological barriers between them and forms the foundation of his grotesque methodology. Jan Svankmajer manages to alienate the context of everyday objects by rearranging and assembling them in such a way that a new meaning is revealed.

The role of the maker is important to the animation film, since the artist is responsible for the ontology of the puppet. Even though Svankmajer is not an expert in puppet construction, since most of his creations are assemblies of found objects, he has a unique approach to his craft. For Svankmajer (2006), there hardly is a separation between the act of creating and collecting. since he sees collecting as the first stage of the production, and compares his process to the approach of alchemists when collecting manuscripts. In his own cabinet of curiosities, Svankmajer’s objects are alive and full of embodies memories and experiences. The order that delineates his collection is the complete antithesis of the chaotic display of objects and hybrid forms portrayed in his films. This leads us back to the motivation behind the practice of grotesque art, as discussed by Kayser; the amalgamation of the realms alongside the absurdity behind the creation of its form as a means of creative expression.

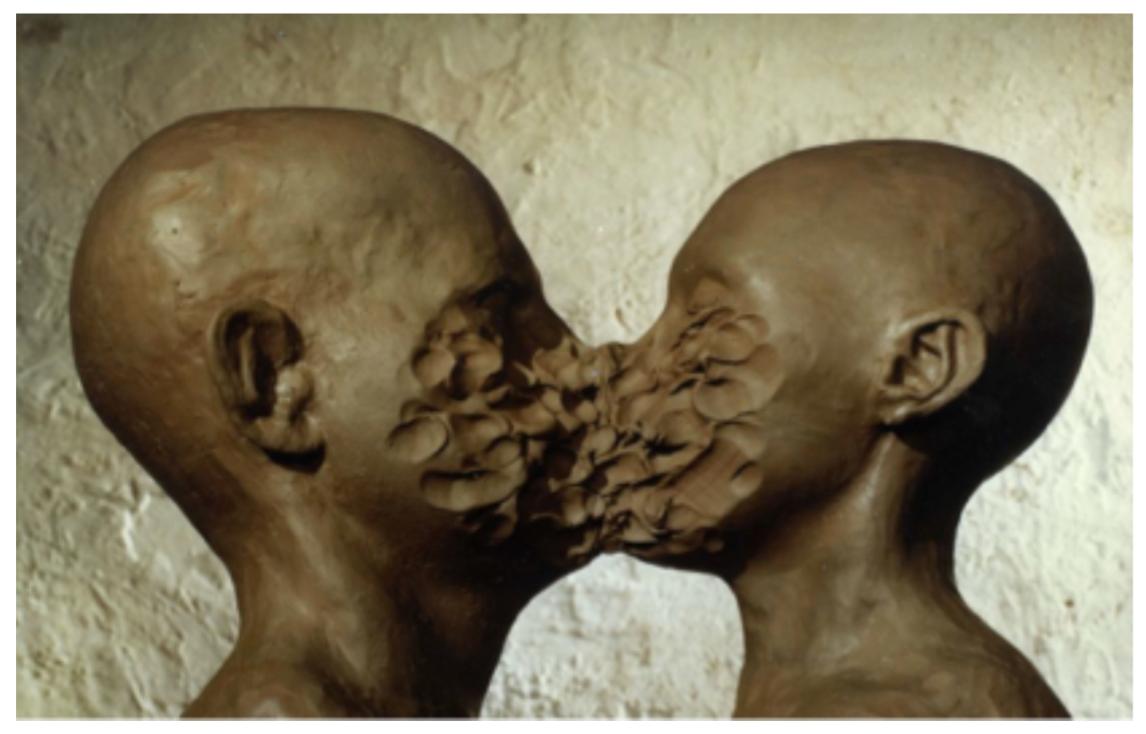

The grotesque puppet in Svankmajer’s films is essentially an inanimate object which has been endowed with the ability to embody life. This puppet as a performative object has its own ontological narrative, which is not similar to that of a real life being. In order to express existence, it has to rely entirely on the energy transferred to its body by the hands of the animator. In accordance with Bakhtin’s writings, the puppet’s grotesque body lies between the realms of life and death, it is part of both an organic and inorganic world, spiritual and physical, finding itself in a state of never completed metamorphosis. Bones, household objects, old toys and particularly food come to life in every Svankmajer film, creating their own rules when it comes to their deformed anatomy. In Darkness, Light, Darkness (1989) various clay organs, a human denture, a pair of eyes, an animal’s brain and limbs gather together into a small room (image 2).

Image 2. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1983). Dimension of Dialogue. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

As other limps try to join, they attempt to assemble themselves into some frightening and disturbing combinations. Among the clay figures, a real tongue suddenly joins in. The film is about the contrasting textures, as much as it is about the unmitigated physicality of putting a cow’s tongue in a small theatrical set. The audience understands that is a real tongue being animated on screen, and there is a feeling of revulsion that comes with it.

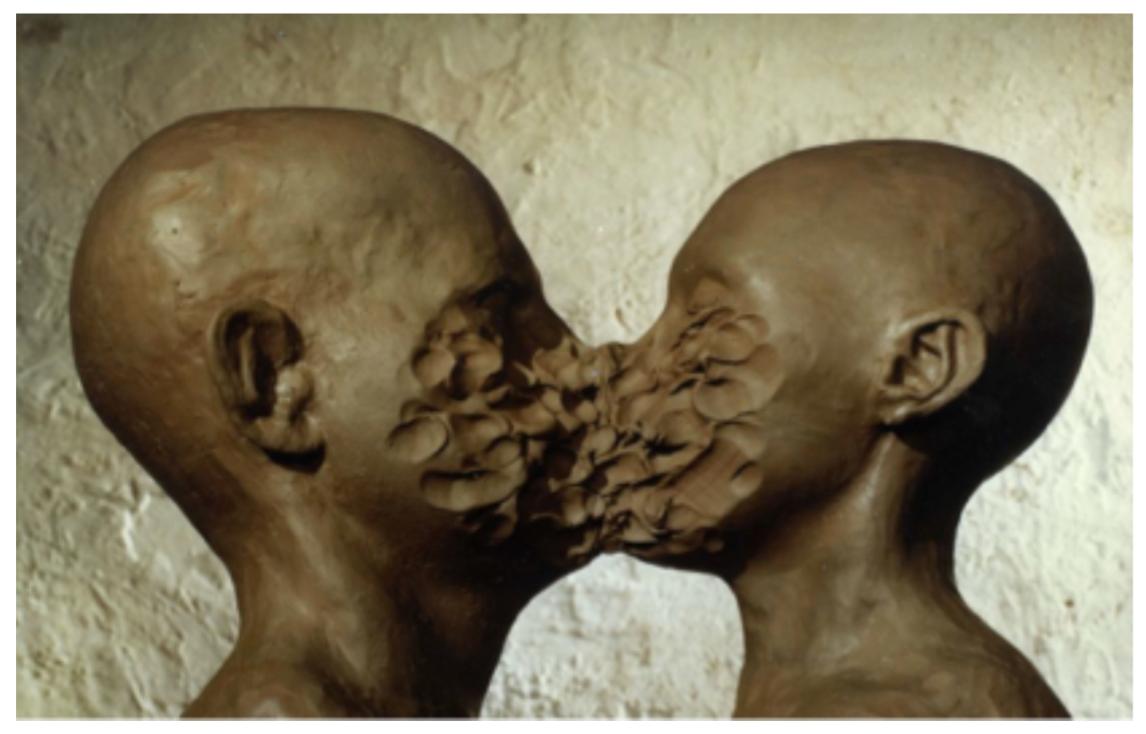

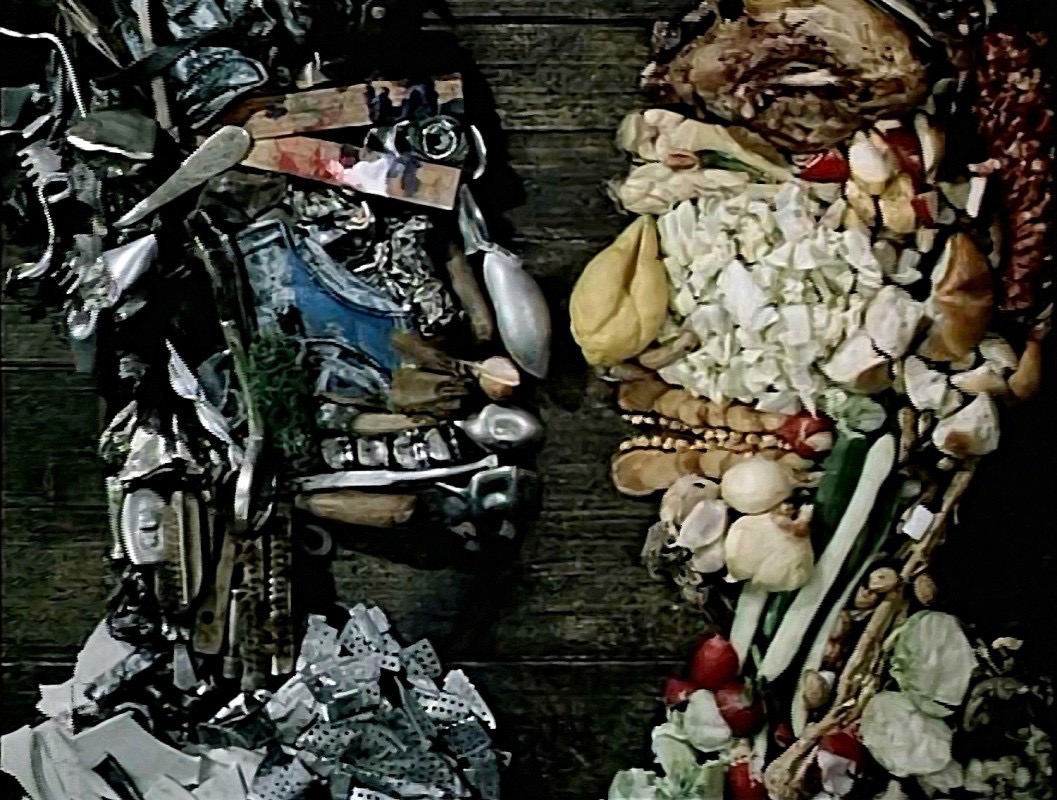

One of Svankmajer’s greatest short films, Dimensions of Dialogue (1983), emerged out of his fascination with the constellation of fruit and vegetable human figures in Giuseppe Arcimbolgo’s paintings. In Dimensions of Dialogue, Svankmajer creates his own version of Archimboldo-like puppets which are reshaped through continuous metamorphoses (image 3).

Image 3. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1989). Darkness, Light, Darkness. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

The film is divided into three parts, each representing a different type of dialogue between two people and the possible ways they can go wrong. The first part feels like a painting in motion, where the perspective of the puppets’ existence is flat but they are themselves three-dimensional, whereas the second and third part shows viewers an interplay between clay figures (image 4). In every single section, the forms attack and start to consume each other, melt into one another, merge into one entity until they separate and regain their identities once again. These grotesque figures are not only in a constant state of metamorphosis but the film thematics additionally deal with matters of the lower bodily stratum. Eating, vomiting, consummating, conceiving and giving birth are all forms of degradation. Using clay, a natural soil material, to portray the puppet’s characters enhances even further the experience of the grotesque and the body’s physical connection to the earth.

Image 4. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1989). Darkness, Light, Darkness. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

In his 1988 film Something from Alice, Svankmajer combines the animation of found objects and a real life young actress in his surreal grotesque rendition of Carroll’s book, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (image 5).

Image 5. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1988). Something from Alice. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

According to Wendy Jackson (1997), Svankmajer claimed that the last time he had read Carroll’s book was when he was a child, and the story’s aesthetic adaptation was based on his unconscious mind and distorted childhood memory of the novel. Svankmajer’s version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is nothing like the Alice films we are used to seeing. The classic characters Alice is encountering in her pursuit of the White Rabbit take on the form of sinister household objects, deformed puppets and disintegrated children’s toys. Alongside Svankmajer’s disjointed narrative there is a macabre dimension to the objects’ physical metamorphosis into bodies of deformed biology with exaggerated forms. The character of Alice is the only one performed by a human and just like in the novel her physical size is constantly changing along with her physical form. When Alice becomes small, she transforms into a puppet that looks similar as the young actress. This malicious cycle of destruction and renewal functions as a reminder of the material body’s susceptibility towards decay.

The rest of the creatures in Something from Alice seem to be trapped in their own representation of nightmarish monstrosity. They are fusions of organic and non-organic matter, amorphous characters with a lack of internal structure. Their disproportionate freakish bodies transform through the artist’s use of taxidermy. These puppets are furthermore dressed in a sort of carnivalesque attire, resembling the emblematic figure of the jester of the Rabelaisian culture of the grotesque as understood by Bakhtin. Moreover, one of the puppets is a hybrid fish with four legs, whereas

another character is a lizard with a birds’ head (image 6).

Ιmage 6. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1988). Something from Alice. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

Ιmage 6. Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1988). Something from Alice. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

These creatures, one can argue, share a likeness with the grotesque fusion figures (such as the frogman) found in Nero’s palace in 1480 (image 7). Jan Svankmajer’s films provide us with a large variety of examples of how the grotesque metamorphosis is represented in stop motion films and its animated characters, and how they can enrich the visual experience of the medium.

Image 7. Da Udine, G. (Painter). The frog/man and other grotesqueries in the Vatican Loggia.

CONCLUSION

Throughout my analytical exposure and research in this paper, I have looked at stop motion puppetry films through the lens of the grotesque, in order to see how the concept helps in understanding the medium and its appeals. I have predominantly used examples from the filmography of Jan Svankmajer to illustrate manifestations of the grotesque that bear on the body of the stop motion puppet as well as on the artist’s creative practice. Moreover, Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the grotesque bodily form and its connection to the lower stratum as a representation of an incomplete metamorphosis provided the foundation for uncovering the grotesque in Svankmajer’s puppets. Wolfgang Kayser’s theory of the grotesque as an estranged world helped to identify the artistic processes which contribute to the captivating cosmos of stop motion animation.

Finally, I would like to underline that there is a gap in knowledge concerning the aesthetics of stop motion animation from a theoretical perspective. The grotesque – with its many aspects beyond the ones discussed in the current paper, such as its relation to the uncanny and matters of tactility –could be a useful theoretical perspective through which stop motion animation’s aesthetics can be investigated in future research.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bendazzi, G. (1994). Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation. London: John Libbey & Company Limited.

Carroll, L. (1865). Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. MacMillan.

Carroll, N. (2013). Minerva's Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gasek, T. (2012). Frame-by-Frame Stop Motion: The guide to non-traditional animation techniques. Oxford: Focal Press.

Harpham, G. G. (2006). On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature ([2nd ed.], Ser. Critical studies in the humanities). Aurora, Colo.: Davies Group.

Holloway, R. (1987). Z for Zagreb. London: Tantivy Press.

Holman, B. L. (1975). Puppet Animation in the Cinema: History and Technique. New Jersey: Barnes and Co.

Jackson, W. (1997). The Surrealist Conspirator: An Interview with Jan Svankmajer. Retrieved December 08, 2020

Kayser, W., & Weisstein, U. (1963). The Grotesque in Art and Literature. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill.

Méliés, G. (Director). (1902). A trip to the moon [Film]. Pathe.

Nelson, V. (2001). The Secret Life of Puppets. London: Harvard University Press.

Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1983). Dimension of Dialogue. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1988). Something from Alice. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

Švankmajer, J. (Director). (1989). Darkness, Light, Darkness. [Film]. Krátký film Praha.

Svankmajer, J. (2006). “Decalogue”. Vertigo Magazine 3(1). Accessed December 08, 2020.

Thomas, F., & Johnston, O (1995). The illusion of life: Disney animation. New York: Hyperion.

Thomson, Philip J. (1972). The Grotesque. London: Routledge.

Wells, P. (1998). Understanding Animation. London: Routledge.

contributed by: Irida Zhonga

About Irida Zhonga

Irida Zhonga is a filmmaker whose artistic expertise lies in mixed media and stop motion animation. She has been working across diverse genres for over a decade and her credits include short films, commercials and television productions. She is currently a Research Master’s student in Arts, Media and Literary Studies at the University of Groningen, Netherlands with a specialisation in Film and Animation whilst also working on her latest animation film 'Man Wanted', a Greek/Estonian/Serbian/Albanian co-production, dealing with issues of gender and sexual identity. In July 2019 she was selected for the ARTWORKS SNF Artist Fellowship Program while in July 2020 she was awarded an ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Educators Forum scholarship. In June 2020 she was voted as an ASIFA-Hellas (Greek Animation Society) board member.