The Pleasures of the Research. Review of Andrijana Ružić's Michael Dudok de Wit. A Life in Animation

(Andrijana Ružić, Michael Dudok de Wit. A Life in Animation, CRC Press, Boca Raton, London, New York 2021, pp. 210.)

Andrijana Ružić's book about the highly acclaimed Dutch-British animator, Michael Dudok de Wit, was recently published by the renowned CRC Press in the Focus Animation series edited by a doyen of animation studies, Giannalberto Bendazzi. These three “factors of prominence” may already alert animation art's aficionados that their 2021 reading list should be extended to Ružić's work.

Leaving the academic prestige aside, the study written by the Italian-based animation scholar proves to be a substantial, convincing and needed contribution to animation studies and an outcome of a well-balanced, passionate and solid research. As much as this publication demonstrates high scholarly quality (it should be especially interesting to animation teachers and students), the language is not overwhelmed by academic jargon which makes it a perfect reading for anybody interested in an art-house animation.

While introducing the subject and methods of her study, Ružić recalls realizing that in spite of wide international acclaim of de Wit's films, no thorough and critical examination of his work exists [1] . For the researchers, such “enlightenment” moments promise a challenging and fulfilling excitement, and one becomes highly motivated to chart the new territories. In order to see a satisfactory delivery of this promise, one searches for the most adequate ways of reasoning that perfectly fit the source matter (here, animated films of Michael Dudok de Wit), but also enable the readers to acknowledge discussed issues as meaningful elements of a culturally important bigger picture.

Ružić's “reader-friendly” writing juxtaposes findings of an extensive research on the new subject with an easily understandable logic of well-established film study methods of analysis and interpretation. The author affirms specificity of animated cinema and, following the sensitivity of Dudok de Wit, she appears profoundly respectful and fascinated with the distinctive qualities of animation. But the scholar does not push at open doors, the methodological consistency becomes almost transparent thus the instance of the researcher never overshadows the central character, i.e. the filmmaker and his life-long achievements.

In her study, Ružić refers to popular critique on Dudok de Wit's films (reviews, festival reports, interviews) and academic writings that in a more or less generalized manner discuss the problems of world and European animation. Actually it is striking to realize how limited scholarship one may find on the “authors” of animated films – the studies dedicated to particular persons whose creative methods or intellectual standpoints made impactful effects on the audiences and other artists. That's another feature of novelty found in Ružić's publication. Presumably this is also the reason behind a specific method she has chosen for gathering and presenting her findings. In large parts, an instance of the objective researcher “leaves'' the pages, and “allows” the instance of the artist-hero to speak. The book is filled with Dudok de Wit's citations from conversations between the researcher and filmmaker in 2016-2020 (face to face interviews, plenty of email exchanges).

Ružić analyses Dudok de Wit's films, presents her own interpretations, reconstructs his artistic biography with the support of his close artistic collaborators, but in a way, the readers navigate throughout this framework following Michael Dudok de Wit's narrative. This is unorthodox but highly interesting approach towards film studies, and certainly this procedure emphasizes an essential notion of Ružić's reading of Michael Dudok de Wit's oeuvre: his films present a wide and harmonious union of aesthetics and worldviews, and the book gives the readers an opportunity to examine their feelings in the mirror of Dudok de Wit's experiences. The notion that can be called an “inseparability of experiences” (creating worlds, receiving worlds created, existing in the world) seems to be already imprinted in the publication's title that acknowledges animation as a specific condition of living.

The book has a clear structure dictated by the development of Michael Dudok de Wit's artistic personality – first two chapters investigate his early interests and inspirations, studies in Switzerland and England, and the director's establishing himself as a creative and trustworthy animator. Chapters three to six discuss his following art-house projects: The Monk and the Fish (1994), Father and Daughter (2000), The Aroma of Tea (2006), and a feature The Red Turtle (2016), all of them well-known to any art-house animation viewer. But that's not the whole value of the publication. A preceding epigraph, various insightful mottos that initiate each subchapter, and five appendix (three of which give even more space for de Wit's personal expression as e.g. he answers Proust questionnaire), Tom Sito's foreword, and an epilogue authored by Yuri Norstein, all these segments smoothly complete the work of scholar who is dedicated to present life and work of an artist in a wide spectrum.

Even though Ružić's admiration for Dudok de Wit's work is easily detectable, it should not be mistaken for a lack of a researcher's objectivity. It is a privilege of film scholars to dedicate their time and skills to study what they cherish. Ružić is sincere about her fascination but whenever she poses statement of appreciation (e.g.: The idiosyncratic mixture of intuition and rationality prevents his quest for perfection from becoming sterile and self-referential and enables it to propel his art, p. 107), she either initiates or concludes argumentation grounded in rigid analyses. Very early in the introduction the scholar indicates a set of aesthetic, filmic and intellectual motifs she finds integral for Dudok de Wit's creative output: (1) storyboard mediating animation phases, (2) timing, (3) refined color palette, (4) light and shadows, (5) absence of dialogues, (6) cyclic time, (7) melancholic landscapes, (8) role of the music score, (9) specific recurrent themes and visual motifs (p. xxii). With an impressive consistency, Ružić unlocks the technical aspects and meanings of each de Wit's film with this key framework. Such approach allows her to thoroughly “report” from the creative processes that have (re)occurred at Michael Dudok de Wit's studio.

While speaking about Dudok de Wit's first professional art-house project The Monk and The Fish (his first out of three Oscar nominations, the prestigious statuette was awarded to him for the subsequent film), the author extracts the components of the project which was at the same time entertaining and poetic (p. 25). It was realized with the traditional techniques and without the use of close-ups. The backgrounds unveil the quality of pleasantly tactile contrasts (p. 30), while visually and narratively the film is built upon the motifs of the arch and the circle. Ružić argues that above all Michael Dudok de Wit was reimagining and artistically merging his impressions on South Europe's architecture and Japanese visual arts. In this part Ružić proposes a category which I find highly interesting for the animation scholars, i.e. “celebration-of-life film” (p. 38), and I hope she will be willing to develop this thought in some other writings.

In an analysis of Father and Daughter, Ružić pays attention to the growth of Dudok de Wit's aesthetic sensitivity that encompasses arranging sequences and narrative flow already on the stages of storyboard composition and experiments with techniques (charcoal, pencil, watercolors, computer imagery, reference footage). She also reconstructs a quite intimate relation between the animator and the music composer. It seems that Dudok de Wit's collaborators experienced somewhat spiritual sensations while working on the project. Ružić quotes Arjan Wilschut, a Dutch animator who said: Watching him work taught me another way to animate a drawing: by thinking about the movement and visualising it, (…) It was a sort of heightened awareness of pencil and paper and movement, a very natural process which I had not experienced before (p. 55).

The shortest chapter discusses experimental, non-figurative The Aroma of Tea of which Dudok de Wit said: Creating a synchronization between music and visuals is like creating a dance (p. 78). Perhaps because of the briefness of this part, the reader at this moment comes to realization that one of the key words used by Ružić and her interlocutors (including the director) is “serenity” understood as a desirable quality of a film experience but also as an ultimate aim for any kind of expression.

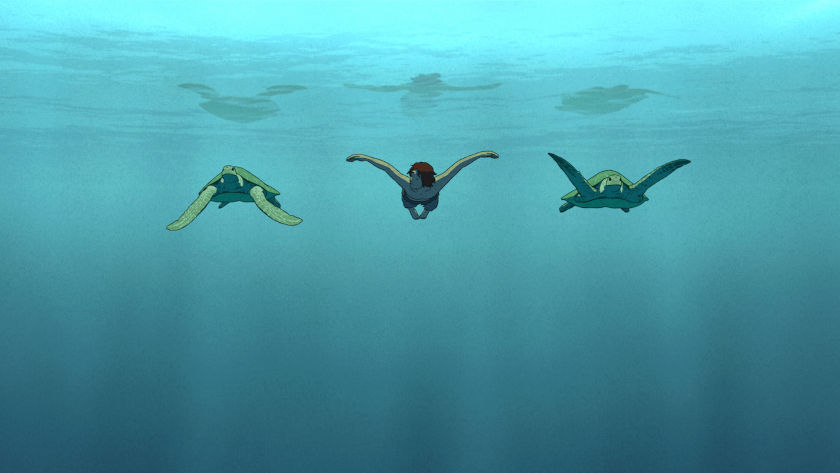

Understandably the longest chapter is dedicated to the highly successful animated feature The Red Turtle created by Dudok de Wit on the Studio Ghibli producers' invitation. In a significant extent the chapter discusses conceptualization of the narrative and script writing endeavour shared by Michael Dudok de Wit and Pascale Ferran. The story that absorbed a hybrid form between myth and fable (p. 87) was conveyed according to the principles indicated by the director as following: (1) emphasizing light and shadow reinforces relationship between animation and background, (2) one or two dominant color per sequence allows to maintain aesthetic simplicity, (3) realism of design and movement (p. 93-94).

The scholar again proves her skills in listening carefully to the “protagonist” when Michael Dudok de Wit recalled particular emotions accompanying the director who has not animated his own film for the first time. She meticulously investigates involvement of several collaborators who worked on the production, among them co-writer Ferran, artistic producer (Isao Takahata), supervisor of background and member of color research team (Julien De Man), supervisor of layout (Eric Briche), another color research team member (Emma McCann), head of special effects animation team (Mouland Oussid), animation supervisor (Jean-Christophe Lie), digital animation team member responsible for the images of the turtle (Dominique Gantois), music composer (Laurent Perez del Mar). Animation is a collective affair, and Ružić demonstrates this characteristic in its full scale.

The chapter is titled a “coronation of a dream” which may suggest a closure of Michael Dudok de Wit's filmmaking career. While the question of Dudok de Wit's future projects only naturally stays open, here Ružić concludes her journey through the director's animated universe by asking about his work towards perfection. The scholar finds this quality in the critically acclaimed feature whose visual language (…) reflects the filmmaker's unique graphic style, forged through the years of joyful and elegant animation (p. 99).

On the side of very infrequent shortcomings that Andrijiana Ružić's book presents, one may notice the author's promptness in applying concepts and categories originating from the Japanese arts criticism to the overtly Western-rooted film material. Even though Michael Dudok de Wit speaks openly about his passion for Japanese culture (from philosophy, through calligraphy to manga), and Studio Ghibli's attention proves mutuality of understanding between the European director and Japanese producers, somewhat generalized intercultural comparisons may bring an impression of a simplification of an otherwise detailed and convincing study.

Having said that, the significance of Ružić's contribution cannot be underestimated. Not only this publication uncovers an “artistic life” from a multitude of angles and may serve as a textbook of how to analyse and interpret an art-house animation (by its definition, a defiant material struggling against any categorization). The greatest strength of Ružić's writing is that she mediates the director's creative personality thus enabling us to come as close as possible (for a stranger) to his most intimate worldviews, fears and hesitations. Regardless one's admiration for Dudok de Wit's film style and sensitivity, or a lack of it, we can imagine the director in his “flesh and blood”, realize the significance of his continuous need for artistic self- improvement, see him as a passionate explorer of animation techniques and styles.

PS. I am grateful to Andrijiana Ružić for acknowledging my criticism of The Red Turtle. As presented in her publication, I am quite alone in my views but I continue to interpret this film as simplified and problematic from the perspective of gender representation. In this context, it was even more interesting to follow Ružić's argumentation and, perhaps above all, Dudok de Wit's narrative. I have discovered that between “I” and “The Author” there is a high wall built from the elements that we perceive and name differently. Many times during the reading I have been recognising the intransgressible differences between myself (equipped with a life experience as I have it, and cultural baggage as I have inherited), and Michael Dudok de Wit (as he is presented on the pages of Andrijana Ružić's book). Ružić’s work enables me to “catalogue” these discrepancies and that’s where I benefit from reading her book. But even the most extensive and conclusive scholarship does not have a capacity to form an emotional bond of trust and identification between the viewer and the film work. This happens in the darkness of a screening room.

[1] In the bibliography the author notes a French-language publication from 2019 whereas Ruzić has uptaken her research several years earlier, see Kawa-Topor, Xavier, Nguyên, Ilan, Michael Dudok de Wit. Le cinéma d’animation sensible. Entretien avec le réalisateur de La Tortue Rouge, Capricci, Paris, 2019.