'Dear Mahsa' by Martin Pflanzer: Animation Short On the Iranian Mahsa Jina Amini

Poetry meets animation meets political events in 'Dear Mahsa'. The animation documentary by Martin Pflanzer powerfully dramatizes the death of 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian student Mahsa Jina Amini (16 September 2022). Amini was arrested by the Iranian Guidance Patrol for not wearing the hijab and subsequently stayed in custody -her death caused an Iranian and international reaction. This reaction was translated first into poetry when Iranian author Ayeda Alavie wrote a poem on that; Bucharest-born (and Germany-based) filmmaker Martin Pflanzer took the task of making the whole thing into an animation short that is still relevant.

Director Martin Pflanzer talked to Zippy Frames, on the occasion of the film's online release (8 March 2024).

ZF: This is an animation short that documents all the paces of the Mahsa Amini death and the following protests, based on a poem by Ayeda Alavie. What was the instance that made you acquainted with the case, and what attracted you to film and animate the poem? The death and the protests itself, the poem and its literary signification?

MP: Actual both. First of all the death of Mahsa Jina Amini on 16 September 2022 has huge significance, as it was the trigger for the current movement against the repressive Islamic regime in Iran. It was a horrible crime against the young Kurdish Iranian woman and she is far from being the only victim. The mostly young people of Iran are protesting with great courage for their human rights and their freedom. They want their lives back. And they are naming the perpetrators and murderers directly. This is a whole new level of the struggle for freedom after 45 years of oppression. In its own way, the film takes part in this and I hope it has managed to draw a little attention to the subject.

And, of course, the poem by Ayeda Alavie was a huge inspiration. It stretches a line back from the current situation to the historic events of the Islamic Revolution. And it shows what it means to be controlled for generations and not to be allowed to decide for yourself. There are these powerful images of the cave into which one is thrown or the voice that is silenced. These images were the first inspiration. And then there is this way how the poem looks inward and shows the psychic changes from fear to resistance. This tells an individual and at the same time universal story.

ZF: Relatedly, did you meet Ayeda Alavie, and what kind of research (textual-visual) did you need to do to depict the world of oppression in Iran?

MP: Yes, we discussed the details of the storyboard and some of the images. Ayeda also contributed creatively to the film, for example by providing the handwriting at the beginning and, of course, by speaking the poem in Persian for the film. Research was necessary for some of the more concrete images: What did Tehran look like in the 1970s, for example? Which images and symbolism were important during the protests?

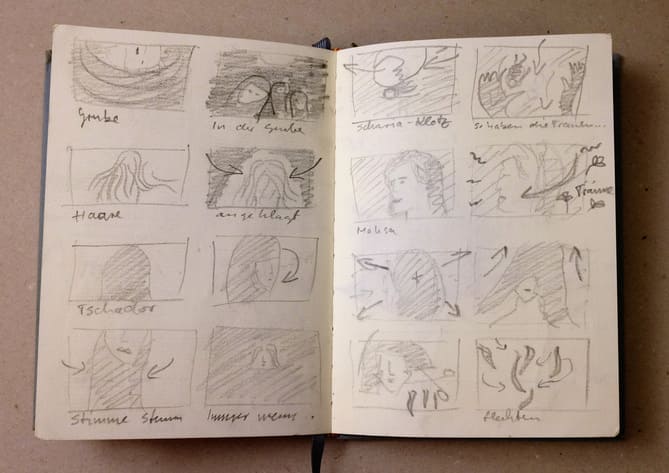

Storyboard excerpt from 'Dear Mahsa'

But besides this, I was focused on the study of movement. The transitions and movements are the most important elements in the film: People fall, hair is veiled or cut off, and waves push you underwater. Since there are no cuts, everything flows into each other. I had to keep checking whether the movements, which were only roughly conceived in my mind's eye, actually worked. I divided more complex scenes into parts of movements. And I studied other films, recreated movements with small models or also filmed myself, which I later rotoscoped.

ZF: How did you decide on the visual look of the film? Were you influenced by other high-profile films, like 'Persepolis' and to what extent? Also, did you draw in hand or was the work done digitally?

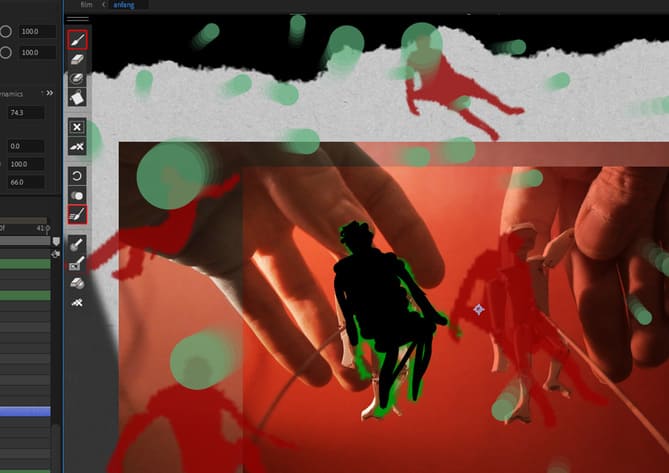

MP: The pictures are hand-drawn on a small graphics tablet directly into the compositing program. I worked with 10 frames for one second. So, after 6 weeks of drawing, my hand was already a bit sore.

For me, the hand-drawn images capture the emotionality of the topic and the moment of creation. The frame-by-frame technique also contributes to this: There is something trembling, restless, and searching. It shows the view inwards. It's as if you close your eyes and search your memory or your subconscious. Tangible and intangible at the same time.

It was clear from the start that it should be this high-contrast style. The harshness of the black and white shows the inner state, the trauma. Burnt-in images. The reduction of the image allows the content to come to the fore all the more. In this way, the images adopt the clear and direct language of the poem.

I would, of course, be very interested to know whether there were similar stylistic motivations for 'Persepolis'. In any case, the graphic novels and films by Marianne Satrapi, whom I greatly admire, have this effect of concentration on me. I didn't think about it during the production of my film, but there is certainly something stored in my mind that resonates.

Watch 'Dear Mahsa':

ZF: The animation short looks like a grassroots initiative that had to state things at the right time at the right place. Did you have any production help/funding or people who were willing to support you creatively?

MP: Regarding production funding: No. I didn't even try to apply for anything because it would have slowed me down and disturbed the creative process. I prefer to work with the simplest means that aren’t expensive, this way I have more freedom. Of course, I can't work completely without money either, so I was grateful later to the festivals that awarded the film also with prize money and to the cinemas that paid a screening fee. This allowed me to partially cover my expenses.

Regarding the creative support: Yes, this happened in the most wonderful way: Everyone in the team contributed spontaneously and out of passion for the cause. And beyond that, everyone also enriched the project immensely. For example, Hari Vorbrugg revealed in his music composition new aspects and possibilities in dramaturgy that I hadn't even realized before. So everyone gave something to the film, which was a wonderful experience.

ZF: This is not your first Iran-based film. You also have another film credit '41 Minutes Iran'. Can you tell us about how this film, and generally, how the Iran question fits into your filmography as an animation filmmaker?

MP: '41 Minutes Iran' was my first film collaboration with Ayeda Alavie. It's an episodic film, experimental, and more like a radio play with pictures. But you can actually see 'Dear Mahsa' as another chapter in it. It is another literary appeal or a 'letter' that sheds light on the situation in Iran. A new addition to 'Dear Mahsa' is the condensed film form.

ZF: It seems that the short appeared shortly after Mahsa Amini's death. Is that contemporaneity a help to you as a filmmaker or a hindrance? Some filmmakers want to have a time distance to be creative, but here it's the opposite. Also, did you have a very fast deadline to make the film or any other challenges (for example, scene issues, editing, etc)?

MP: The relatively quick production and release was simply an emotional necessity to me. With other projects, I tend to take things slowly, but here everything was already there. On the other hand, I didn't have a deadline and the film was simply finished when it was finished. It was a liberating feeling to be able to do something in the face of the moving situation. In this sense, contemporaneity was a help.

I'm not sure whether the contemporaneity helped the film's presence at festivals. I would say yes. The festivals recognized the brisance of the topic and also had the political courage to show it was certainly happy to have such a current work. During this time, many works were created everywhere in solidarity with the people of Iran. It is wonderful when festivals give this solidarity a place, some festivals have even shown the film at the opening.

ZF: What do you think of the animation documentary genre in general? Do you have animation docs you admire?

MP: I love it. It's a wonderful way to tell stories that are rooted in reality but go beyond it. Animation can show what you otherwise can't show or sometimes aren't allowed to show. The latter is actually often the case with Iranian films, for example, the recent documentary "Seven Winters in Tehran" uses a miniature replica to show the interior of Evin prison, where Reyhaneh Jabbari was held before she was executed. Another example that I saw at Dokfest Munich 2020 was the short film "The Unseen" by Behzad Nalbandi. In it, the "cardboard sleepers", i.e. homeless people in Iran, are replaced by cardboard figures to protect their identity.

For me, it is also particularly exciting when films are rooted in documentary but give it an essayistic, personal, and poetic color. For example, I found the Chilean stop-motion film "La Casa Lobo" by Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León incredibly impressive. The film deals with the history of Colonia Dignidad in Chile but is not entirely documentary. Nevertheless, it deals with the story by masterfully interweaving real fragments into a kind of associative stop-motion nightmare.

Compositing in 'Dear Mahsa'

ZF: 'Dear Mahsa' tells a simple and powerful story. Is this the kind of story you also want to tell in the future? And what do you have in mind (or already in development, perhaps), in the future?

MP: Yes, I like simple stories if there is a truth or deeper level to be found in them. These are precisely the themes that I also revolve around, which is why dealing with them artistically is an important process for me. And I want to continue exploring visual poetry, also in connection with documentaries, and I keep collecting small ideas that I come across in everyday life. Maybe one day I'll combine this collection into a film again.

Credits:

'Dear Mahsa', 2D animation, 2022 (5'15'', Germany)

Directed and animated by: Martin Pflanzer | Audio: English or Persian | Subtitles: available in English, German, Spanish, and Italian | Poem by: Ayeda Alavie | Original music by: Vorbrugg & Söhne | Recited in Persian by: Ayeda Alavie | English translation by: Martin Lickleder | Recited in English by: Claudia Kaiser | Spanish translation by: Silke Kleemann | Italian translation by: Trame Indipendenti | Special thanks to Susanne Bräunig

About Martin Pflanzer:

Martin Pflanzer was born in Bucharest in 1985 and after spending his childhood and school years mostly daydreaming he studied art and multimedia at the LMU Munich. Besides his work as a graphic designer for Bavarian television, he is often looking for new ways of expressing himself in image and sound. This resulted in various installations, illustrations, photographs, paintings, animations, stage designs, and books.