Friendly Fire by Tom Koryto Blumen

A football incident in animation by the Israeli filmmaker Tom Koryto Blumen that brings to mind Jean Renoir's 'The Great Illusion' (1937). Guy, the soldier, is standing on his guard post, and Ali, a Palestinian boy, engages (somehow by accident) in a friendly football match -and, for a brief moment, they are connected. And then they get disconnected again.

The short animation film 'Friendly Fire', a student film from the Bezalel Academy of Art, became a festival favorite (more than 80 screenings in animation and film festivals) and a finalist for the Student Academy Award.

Its wall animation technique is also distinctive and reveals a grassroots effort. As part of our Shorts Corner submission process, Tom Koryto Blumen premieres his film online. We talked to him.

The Animation Film and Its Beginnings

It all started with a conversation with my father, who fought in the First Lebanon War. He shared a memory that stayed with him —playing football with local children. For a brief moment, it felt like a shared language without words. That utopian moment ended when the children's parents called them away from the Israeli soldier, and my father's commanders warned him not to get too close to the Lebanese population.

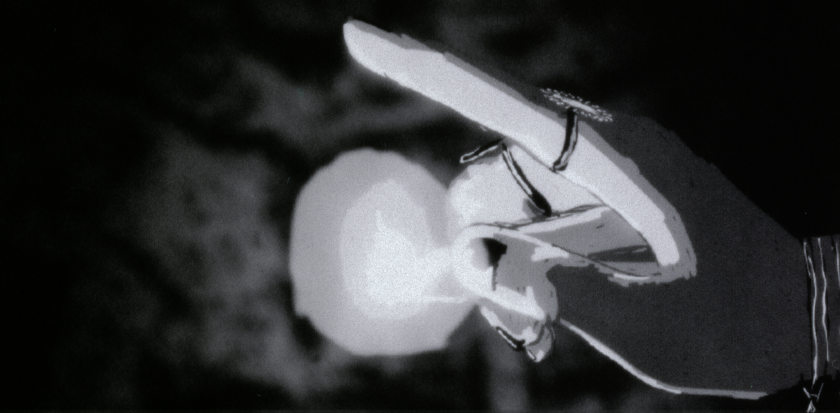

When I was developing my graduation film, I was deeply involved with graffiti and street art, and I had come across wall animation online - short loops or more experimental films like Blu's, who became a central inspiration for me. I decided to be the first to create a narrative film with consistent characters using this technique.

But, because the technique is so complex, the story had to resonate deeply with the medium; I realized that the football game story contains the film's core. As someone who has always used walls as a canvas, West Bank barrier was the perfect location for the film —a surface that tells the story of generations caught in one of the world’s most complex conflicts.

Biggest Challenges

The heat. Filming during June-July in Israel meant temperatures soared above 40°C at midday, with harsh, direct sunlight. You can see the lighting shift between frames, clouds moving across the sky, and even the paint drying in real time and changing its shade on the wall. Βut the imperfections created the language of the film, and became an integral part of the film's texture.

Initially, I animated directly on the West Bank barrier, but heat, lack of electricity, water, and the risk of arrest made it nearly impossible. With the deadline nearing, my father and I decided to build a 3.5-meter-high, 10-meter-long concrete replica of the wall in his backyard. Most of the film was shot on the replica.

Faceless Characters Become Part of the Animation Technique

From the early stages of character design, I knew I wasn’t going to animate facial features. It takes too much time, and from my experience painting murals, I knew that at the scale and resolution I was working with, the details would get lost. In retrospect, this allowed me to convey a story about the lost identities and silenced voices (unique stories, character traits) of individuals in war. Each person becomes a symbol of the society they represent, often masking the ability to see beyond those social labels. All that remains is what they are perceived to represent, absorbed by the identity of the society they are associated with.

A Lot of Preparation and Unexpected Incidents

Because this technique is so difficult, and since it's nearly impossible to fix a shot afterward, much like in most stop-motion productions—I worked closely with a very precise animatic. Most of the shots in the animatic were already as accurate as the final shot, just done in 2D animation. The final shot of the film ends with a fade to black, which I hadn’t planned. But it wasn’t a post-production effect—it was a physical change in lighting because the sun had set, and it got dark. The environmental conditions simply forced me to end the film with a fade to black, and I accepted it.

Schedule

I was given a year to complete the project. I wanted to be as prepared as possible before starting the animation phase, even if it meant putting the production stage under time pressure. I dedicated significant time to writing the script and thoroughly completing all the pre-production work. During this period, I also built the replica wall, which required two months of intense, hands-on effort. I completed the animation over the course of three full months, working seven days a week, every day from 7:30 AM until sunset. I couldn’t afford breaks longer than 20 minutes, because any shift in lighting would have created visible jumps in the shots.

Collaborators

Everyone credited in the film volunteered their time — my wife, my grandmother, and friends who helped paint the wall. The music was composed by my best friend, and I paid him with a bottle of whiskey. My uncle did post-production and was also paid with a bottle of whiskey. Sound design was done by my father-in-law, even though he doesn’t like whiskey.

Music & Sound Design

The music was carefully composed by my talented close friend, Nitzan Rom, a professional film composer. In the film, the music plays several key roles: it evokes a sense of war ecstasy through the use of war drums and occasional synchronization with the sound of tank fire, creating a growing sense of tension in the air. At the same time, it introduces a subtle oriental undertone and embeds a layer of critique through musical fragments of Hatikva, the Israeli national anthem (especially in the film's closing scene). The inclusion of Hatikva, a song traditionally associated with national hope and remembrance, critiques the way national symbols are used in the context of war and Memorial Day. By echoing Hatikva in moments of destruction, the music raises questions about the gap between the ideal of hope and the reality of repeated cycles of loss.

Contrast Between the Individual and Society

The child and the soldier choose to create their own personal peace by playing football, and they begin to speak a shared language. Once society steps in, what started as a friendly, intimate game between two individuals turns into a confrontation between two groups—burdened with history, emotional baggage, and aggression.

The act of erasing each frame in grey color on the wall, along with the “scars” left by the animation, is meant to express the destruction that war leaves behind -not only physical damage, but also a lasting scar. My grandfather was killed in the Yom Kippur War, and I grew up in the shadow of my mother’s deep pain, having lost her father when she was just five years old. My father carries in his heart the memories of the Lebanon War and has struggled with PTSD. Whether I like it or not, my life has been shaped by war and the complex reality of the Middle East.

Feedback from animation festivals

In Israel, I was initially concerned about harsh criticism, particularly regarding my portrayal of the army and the way Israel handles the conflict. However, the feedback I received recognized the complexity I aimed to convey. Internationally, I feared reactions would be one-sided, overly supportive of the Palestinian perspective. To my surprise, the responses were thoughtful and promoted a dialogue on the broader struggles in the Middle East, life under the shadow of war.

I also received positive feedback specifically on the technique, with many appreciating how it supported the narrative and helped communicate the themes effectively.

Would you have made a different film today?

Towards the end of the festival tour, October 7th happened. I felt betrayed. I had just made a film about coexistence, about peace being possible with the people on the other side of the wall, and that vision shattered into pieces. At the Nova festival, where the massacre took place, I lost a dear friend from the Israeli graffiti community, Inbar Haiman. She was murdered, and Hamas still holds her body. In the days that followed, I couldn’t even look at my film.

Today, I feel that my film still carries the same message I originally intended. But the film captures a moment in time that will never return—it preserves thoughts and perceptions I had back then, while the reality around me constantly changes. Thus, the film becomes a political work and a kind of autobiographical document that immortalizes a moment in my life as a person and creator living in the Middle East. And there's something beautiful about that, that's exactly the power of cinema. I hope one day this football game will stay friendly, and the wall will stop being stained.

Watch 'Friendly Fire'

About Tom Koryto Blumen:

Tom Koryto Blumen is an Israeli animation filmmaker who graduated from Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. His film 'Friendly Fire' (2022), was nominated for the Student Academy Awards®. The film showcases a distinctive hand-painted animation technique, which he developed in order to mix together his passion for graffiti and animation. The film received widespread international acclaim, won the CILECT Prize, earned 12 prestigious awards, and was selected for over 80 animation and film festivals worldwide.