'Letter to a Pig' by Tal Kantor Film Review: Or How Do We Remember, Suppress, and Narrate Holocaust 80 Years Later

Among various features of the Tricky Women / Tricky Realities International Animation Festival (Vienna), I greatly care for the “Good Practice” forum. During this event different women animated film practitioners (animators, distributors, researchers, etc, etc) go deeply into the complexities of their work. The energy of occurring interactions and the multilayeredness of the speakers’ interests makes this event an exceptional and inspirational space within the European animation art-house circuit.

Tal Kantor’s presentation of her award-winning 'Letter to a Pig' (Tricky Women’s Jury Special Mention) was not only a great speech that skillfully merged making-of format with discussion on intellectual and cultural inspirations but also a highly original supplement to this one of the most accomplished films of the 2022 animated art-house season.

I fell for 'Letter to a Pig' the first time watching the film. Kantor’s daring subtlety in changing the narrative scope of the story about the Holocaust trauma struck me as something utmost brave, long-time needed, and necessary in order to cultivate the memory of pain and trauma as meaningful despite the almost centennial time distance between the Shoah and today. As an author, Tal Kantor is self-aware in regard to the concerns of ethics and filmmaking. Poetry and ambiguity inherent to the animated film language should not overshadow or dissipate painful truths expressed with this medium.

The film touches on the subject which remains rarely - if ever - discussed. In his Zippy Frames article, Mikhail Gurevich delineates its subject matter area as a lack of historical memory of incoming generations as well as the nature of ‘indirect’ remembrance.

I would argue, however, that the semantic core, lies elsewhere - and it is to be found along with the mindset and agency of the following generations, but not of the survivors themselves. The voices heard here are those who were born into traumatic memories of World War II. At the same time, they were socialized in a system that interweaves martyrdom with apartheid. The question is what do they do with such a heritage, what kind of lesson the youth from contemporary Israel takes from what happened in the distant parts of Central-East Europe. I do not read this question as a reference to the lack of construction of an ‘indirect’ memory, but rather as addressing the actual and current Holocaust meaning and symbolism.

Limited time only: Watch the 'Letter to a Pig':

In her speech, Tal Kantor mentioned three fears which have followed her since the day the idea of 'Letter to a Pig' emerged in her mind, and as I would expect, have not really left her ever since. Those fears discussed publicly, appear to me as keys unlocking the interpretations (plural form - deliberate) of Kantor’s film.

The first one regards psychological confrontation with the trauma and is related to exposing oneself to research and analysis on the subject matter of mass genocide and strategies of survival. Detaching oneself from your family’s trauma may be a traumatic experience in itself. Here, in order to become an autonomous individual who nevertheless functions along with her group, Tal Kantor dives into her deepest and darkest heritage. Chaim, the character of the survivor, speaks of his memories to the class of current teenagers. His story explores a variety of emotions upon which storytelling of the Holocaust is constructed - panic, loss, fear, adaptation to the humiliation as a survival strategy, feeding on anger that grows into a dream of revenge, anguish upon completing the revenge, bitter happiness that the listeners, the kids of today, cannot in fact understand the survivors’...

Chaim reads out his 'Letter to a Pig' - an animal that helped him stay hidden, who he previously despised but loved eventually. The question of “what the pig stands for” returns through the film. We see the pig character in its various appearances - from a documentary-like visage known from empiric reality, through a creature of monstrously grand dimensions resembling dreadful caricatures from the final sequences of John Halas and Joy Batchelor’s ‘Animal Farm’ (1954), up to the heart-warming image of the cutest and tiniest piggy held in teenage girl’s arms. Kantor called the pig the “ultimate Other representing our vices and biases” and refused to make our understanding of this metaphor more particular and concrete. She is right to do so; there is too much important intellectual and moral content to deal with and so we cannot be aided with simplified, clear-cut, and one-sided answers.

From the first viewing of the film, I was inclined to see the pig as an instance equal to the survivor - as I imagined, to look at both of them through the eyes of the kids in the audience. I see youth as too terrified to ask more questions, too tired of the martyrdom, and too traumatized with the past to feel it anymore while the pain and sorrow of contemporaneity are being silenced. A pig, a magical helper from the story of Chaim’s survival, might seem to the new generation as a legendary creature that is relevant no more unless they (the kids / us) become active agents inside this story.

| Related: In Other Words by Tal Kantor |

The storytelling constructions revoked by Chaim come from the testimonies which were written down, declared, and expressed in the years after the Holocaust. They are to be found in the works of artistic literature, creative filmmaking (live-action and documentary alike) as well as mainstream culture. They come from the courts’ records or other sources surveyed and analyzed by the researchers. Those storytelling constructions are part of communication in Jewish households. And this is the second fear that the director mentioned, she wanted to break away from the generationally-sanctioned Holocaust narrative - is it even possible? Is it ethical? Does she have the right to do so? Is there another story beyond the multi-emotional 'Letter to a Pig' read by Chaim?

Kantor confronts the viewers with the scene of “Memorial Day”, a routine element of the education system in Israel, which as we understand from the film, relies on weaving remembrance of the Holocaust (meetings with the survivors) with daily routine activities. Such entanglement comes as radical and shocking but eventually, we realize that this is where the passing on of the traumatic heritage leads. It seems that Kantor asks the question if the Israeli society is ready to think of how to go forward without forgetting, suppressing, or dismantling the painful meanings of the past. This question is urgent because prolonging petrified narratives deprives the stories of real emotions, hinders empathic communication, and makes excuses for egocentric silence.

The third fear shared by the director regards her unwillingness to comply with the characteristics of the war movie, a genre demanding depiction of brutality and fast-paced action. These are not the qualities of Kantor’s artwork and fortunately, she does not obey them. She actually does something very interesting that could be a subject of a separate article.

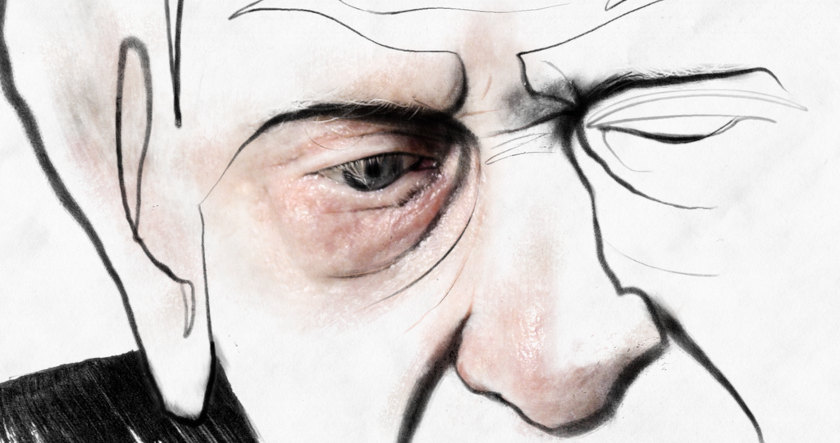

Kantor plays with the formulas of the art-house animated documentary by artistically reworking live-action, fully edited footage. Such material becomes a referential base for various mixed-media operations with animated film means of expression and techniques (among them hand-painted animation). Using the language, techniques, and above all aesthetics of documentary filmmaking (even the most iconic motif of “talking heads”), Kantor has never been farther away from the documentary approach. 'Letter to a Pig' is a fully creative, imaginary artwork that refers to the hardly tangible subject matter of individual and collective trauma.

Kantor admits that at the beginning she wanted to make a film out of the memory of a survival story she heard at school. Confronting her former classmates, she realized that none of them remembers the testimony in question. It is a film about the memory and subconsciousness of the younger generation, she says, and though she means a younger generation of Israeli people, this framework is greatly relevant to all the heirs of Holocaust trauma in its full geographical and cultural scope. Kantor speaks up for Israelis, yet her voice is powerfully heard in the whole central-East Europe, a territory once meticulously mapped by Adolf Eichmann. All around this area, there are other kinds of Holocaust narratives that share the backbone of Chaim’s testimony, and they all involve discourses of fear, loss, humiliation, and vengeance.

For decades we’ve been sincerely repeating: ‘Auschwitz must never happen again.’ And now we ask ourselves how to carry on in the times when the last survivors are passing away and their stories became petrified; when traumatic memories became systematically entangled with daily routines; when the collective memory blends the events of World War II with any other “story from before” into a painful but distant legend. It is not a provocation; asking those questions is what we are obliged to do.

contributed by: Olga Bobrowska