De-Re-Constructing Memory and Re-Documenting Times: Notes on the Margins of Animafest Zagreb 2024 Programs

This year I didn’t visit Animafest Zagreb (June 3-8) in person, alas; so, there were no immediate live impressions to record and report, only of major competition films in distant viewing. Time is passing; thus, in this retrospective, by necessity, I ended up with what had become itchingly imprinted in recollections – just at a certain selective topical-problematized angle.

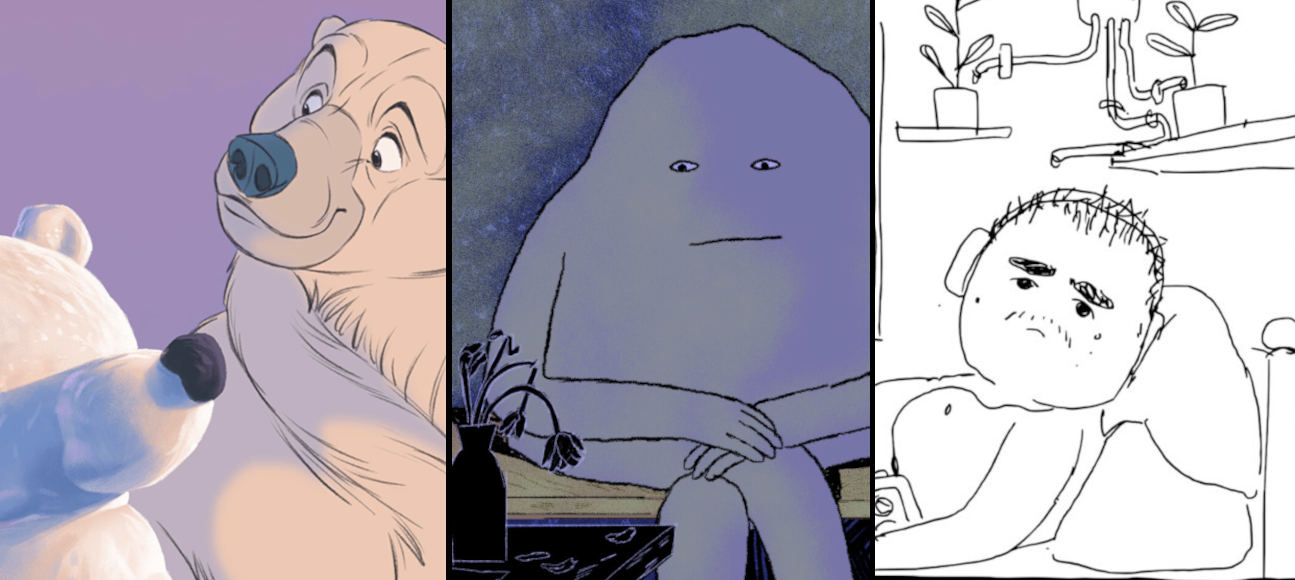

In the main competition, two Canadian films stand as though in ambivalent juxtaposition, or complimenting each other in a complicated way. Moïa Jobin-Paré in ‘Families’ Albums’ (2023) follows her signature method – exercises in mixed media (or rather hybrid forms/ techniques, as self-annotations stress), from old-school analog (including rather exotic, like scratching silver-processed photographs – her device of choice) to digital, supposedly, machining. But in all that here she also seems to shift into the mixed modality, oscillates between distancing and close look; coldly playful exploring, exploiting the sheer material – and meditating upon its semantic-sensual train. And between almost abstract imagery in intricate moves to the tangible surreality of body parts or landscape fragments in midair of the emptying screen, as if some cutouts from coloring book – to shadows of protagonists-owners-subjects. Those, who are inhabiting this semi-vanished universe of lives lived once, imprinted here to be preserved, or maybe exactly being recovered and retained right here and now…On the surface, the film talks about the principal fragmentation of memory – manifestly so through the techniques and devices involved – but also perhaps, on a deeper level, about the (artistic) power to de-recode and resurrect its integrity and meaning. And besides, offers a remark on the materiality of memorizing – even if illusory, scratching over the light-life-memory sensitive layer.

Families' Albums

‘Entropic Memory’ (2024) here as if takes up the relay right at certain crucial points. Like the ‘materiality of memory’ (the ‘physical support’ of it, in director Nicolas Brault’s articulation) – and insists rather on its quite vulnerable, if not ultimately ephemeral dimension, by virtue of the destructible by definition nature of a given data-record medium as such. Moreover, we are invited to witness the very process of this destruction, slow and steady, and painfully hopeless, as it feels. What might be a slight consolation is perhaps the character of imagery employed: at the start, it looks just an exercise in almost abstract forms, or just the texture of estranged photographic imagery in extreme close-ups. Only step by step the figurative facets would become recognizable – paper-carton, photoprints in albums (yes, the same ‘family books’) being consumed, ruined by water, as finite entropy agent… or wait, aren’t they rather, as it should be in nature at large, not lost, but instead being transformed into a different state of matter. Still, in the end, we would see, or guess, a hint to the photo-picture on the vanishing list, albeit shadowy, faded, ‘entropic’, but nevertheless, again, ultimately preserved or resurrected, if only by assumption.

All this is being played out, of course, within maybe ‘entropic’, in turn, framework-boundaries of our artform proper vs. broader experimental filmmaking or media-art. And while the latter film won exactly the Golden Zagreb award (specifically reserved for ‘innovative artistic achievement’), both of them would then meet again on the same edgy ground in the Annecy Off-Limits competition.

Entropic Memory

Some colleagues tend to view ‘Entropic Memory’ (and by extension I might include in this field ‘Family Albums’ as well) as a sort of ‘non-narrative animadoc’. A tempting albeit a bit shaky proposition. If so, then, here awaits an intriguing twist: by Brault’s self-explanation, having been initially driven by the real-life disaster – when the family archive was severely damaged in his basement flооd – he would then recreate this dramatic experience anew. First in installation, with stereoscopic effects-footage; and later animated simply using just water spray and fan in the old-school frame-by-frame movement of paper under drops accompanied by a stormy soundtrack. In such a case, though, we face rather a docudrama of a certain kind, reenacted by this (im)material cast.

In this light, we can move to a more concrete-tangible biographical-historical ‘memorization’, of personal lives-biographies in times that shape them, manifested here even within certain distinct chronology. First, in the Panorama program. The starting point in the timeline is clearly marked: film ‘1976: Search for Life’ (Netherlands, 2023) – where/when family, young parents with a baby, trip to their lares and penates parallels-echoes with something of a Martian chronicles of the day, reportages of NASA Viking lander mission. Tess Martin, a visual artist at large, frames this, literally and figuratively, in a parallel montage of home shooting (from the pre-video era, obviously) and TV footage, in bits and fragments; these are repetitious or remixed, against the backdrop of real-photographic in/ex/teriors – or rather directly inserted in this flesh, via television set or, even more so, in mapping-imprints. The reality of memory, the stuff of documenting, then, bifurcates and blurs; as such, estranges. Maybe from the inner perspective of the future to come, our present-day overwhelmingly-total quasi-documentation of every second in an insane kaleidoscope of screens. In any case, she states among her main thematic drives “the onslaught of time and the precariousness of memory”. Expanding the known-trait maxim: “The past is a foreign country” – maybe it’s altogether another planet.

1976: Search for Life

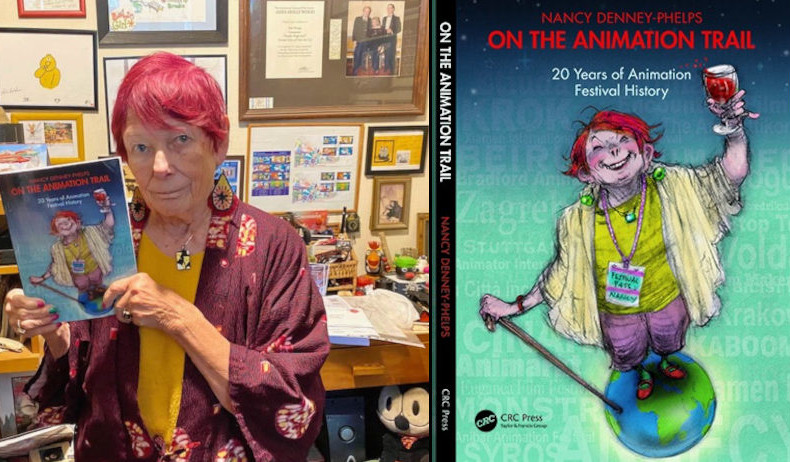

Now we jump a few years forward, and in a different territory (and at the time almost another world from and for the previous observer, perhaps). In the film ‘The Car that Came Back from the Sea’ (dir. Jadwiga Kowalska, Switzerland, 2023) chronotop (time/place image-continuum in Bakhtinian terms) is indicated openly from the start – early 1980s Poland. Crumbling existence, empty store shelves, except for bottomless vodka supply, protest rallies, riot police with batons, no life prospects to speak of – amidst and passing by all this the friendly gang of youths rides in a semi-clapped-out car to the Baltic coast, for a breath of seeming careless freedom, or whatever. Everyone talks of fleeing abroad, and that actually hints at a more precise historical point: probably the summer of 1981, before martial law was imposed in December of the same year and borders sealed. More conventional, surely, documenting-memorization, more customary dotted narrative, in sketchy light drawing – nevertheless, well carrying the weight of still not that conventional task, certain historicization of biographical memory, nostalgic for one’s young years-hopes-despairs, no doubt, yet capable of distancing, de- and re-contextualizing individual-collective experience, in a lightly ironic tone of reflection.

The Car That Came Back From the Sea

And then – back to the main competition – we would step further into this decade, and to the dubious edge of the (then) ‘socialist’ realm; and further into variations of documenting. In the directors’ statement Veljko Popović and Milivoj Popović define the sub-genre of their joint work ‘Žarko, You Will Spoil the Child’ (Croatia, France, 2024, having won the festival's Best Croatian Film and Audience Award) quite directly and unabashedly: “This animated film is a documentary and a personal life story of one girl, town, and country.” Indeed, this lighthearted on the surface, done in some childishly-touchy drawn-collaged stylistics, coming-of-age narrative, turns out to be also ‘historicized’, even with a certain almost sociological perspective. “The 80ties in Yugoslavia were a time of shared experiences. We all had the same furniture, and our fathers rode the same cars, all manufactured by our countrymen. We all shared a collective childhood.” Thus, the confession of love for grandparents would incorporate on equal footing their young age photos (from, yes, family albums, we shall assume, where else) and portraits of Marshal Tito (whom the little heroine dreamed of marrying in her tender age). Not dwelling heavily, though, on the ideological matters, rather treating lightly (from the honest little-girl perspective, after all) fuss and chasm at the family table and around – even at Christmas with marks of compromise between Catholic and communist creeds, and when the New Year's Eve turns to be the last celebrated in peace. Firecrackers turn into rocket fire, the 1990s are out there already, and war with them – indicated by its intrinsic imagery, of course, up to inserts of TV chronicles. Roadblocks, tanks on the streets, bombers in the air, and the happy family shelters in the basement. But the heroine-narrator wouldn’t go deep into that either: “I’m not gonna treat the war as a joke cos it wasn’t” – she just refuses to “talk about the ugly things” in this love letter… Fair enough. Although, let’s suppose, the trauma hidden deep in memory, mitigated or not, still informs it in some way. Here it seems to add a tint to the bittersweet taste and tone. And at the larger scale of things grows into yet another dimension of our theme.

Zarko, You Will Spoil the Child

Traumatized memory politicizes, almost inevitably under the circumstances; the overcoming of trauma intersects with the politics of memory; in retrospect that can be not less intense-dramatic, the past actualizes as the lasting present, one continues into the other.

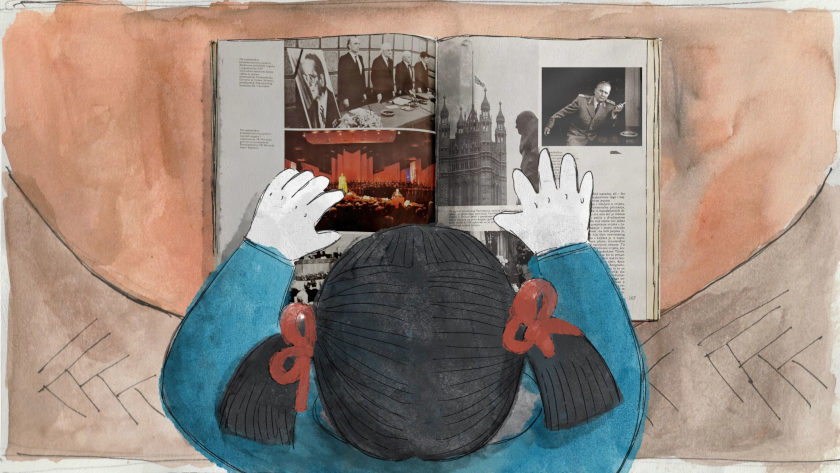

Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña straightly state that their ‘Notebook of Names’ (Chile, 2023) “is a memorial in film format, so that the names and memories of the minors who were victims of forced disappearance by the military dictatorship in Chile remain resounding.”. Voice-over narrative-commentary, calmly passionate and tense, tells how ‘they’ – the perpetrators of all hues, apparently – lied and hid, scraping off the traces of crimes and victims; rubbing out the social, historical memory. And then, half of the film's eight-minute duration, we’ll be hearing exactly the martyrology of names read aloud one by one – thus being saved, restored from oblivion. This goes on the backdrop of notebooks – be that worksheets, registration books or adolescent diaries – pages and sheets at scrolling through, drawing on, being filled with casual flourishes, scribbles, doodles, and objects-signs of lost habits-hobbies-passions, future life paths lost before having been lived through. And finally, black marks, like tire treads on the road, or blackening clouds, are about to eat out to the end this written-drawn world-pages-memorial, and burning the paper matter fire would show its deadly touch. Somehow, that echoes again the very same family albums, in shadowy or watery iterations; in a half-way, transitory state of entropy-in-the-making – probably, hopefully being stopped, interrupted on its onslaught.

Notebook of Names

But then here comes the turn of yet another kind-stage of entropy – a cultural, even linguistic one; along with the sense of identity and belonging. Irina Rubina – originally from Russia, has studied and worked abroad for a number of years already, currently based in Germany – sees and feels this clearly and sharply, and takes a risk to deal with it in a desperately brave gesture. In ‘Contradiction of Emptiness’ (Germany, 2024) she gives up her staple freewheeling jazz variations for almost static and semi-abstract, albeit charged with reserved tension, punctuated flourishes on the margins, graphics of pin screen (its unique-elaborate ‘L’Alpine’ replica in Quebec City) – and for the sake of saying, articulating literary-verbally, in direct first-person speech: “The language in which lullabies were sung to me kills. And I am with it. And the lullabies fall silent…” She first reads in voice-over in Russian, to later switch to her ‘adopted language’, German – that also had been tainted by killing, with silenced lullabies too, some eighty-plus years back; and with the memory of that comes, or must come, responsibility, and vice versa.

Contradiction of Emptiness

And with that also comes another kind of ‘documentation’ – actually, Rubina protocols the zeitgeist of the moment. For those not in the loop: the thorny-mirky issues of language/culture guilt/responsibility, in the long shadow of Russia-perpetrated war especially, nowadays are in the heart of hot-angry-twisted discourse, both cross-borders and amongst Russian intelligentsia itself, be that newly 'relocated' or still homeland-bound. Rubina must definitely be well aware of that – and dares to step in. Recalling canonic Adorno’s saying on poetry after Auschwitz, she laments in her director’s statement: “All artistic and historical reflections have not been able to prevent this war”. Still, or moreover, she puts some hope in her ‘intimate cinematographic scream’… what else is left. Even if, to one’s taste, somewhat too plainly spoken and restrainedly imagined, that shall stand as yet another testament to the human condition of here and now.

Here are the difficult issues of and with inherited and embedded ‘cultural code’ proper – to be worked out, perhaps, to a more complex and nuanced degree somewhere in historical perspective. The emptiness is destined to be filled anyway; that’s perhaps the principal contradiction here – yes, painfully dramatic, but maybe a fruitful one in the end.

The physicality of memory, as viewed in those snapshots from the Animafest Zagreb 2024 lineup, meets-confronts its metaphysics; biographical baggage hits the train of times, and historical settings. And – all hands on deck! – artistic means of such various kinds, from basic to borderline-edgy, are called to catch, fixate, and document those effects, discoveries, dramas. Probably, somewhat changing the way the landscape and thesaurus of the artform in its broader context.

Animafest Zagreb took place between 3 and 8 June 2024.

contributed by: Mikhail Gurevich