Animafest 2018 Feature Competition Or Why Animated Cinéma d'Auteur Is Not Dead (Yet)

We've Been Blessed with Fine Programming

Praise be the selectors. None of the eight works in the competition has given me a headache (though I did experience neck pain after spending long hours in the cinema seats). Animated feature production is rather a realm of the market than artistic experimentation, yet the selection has successfully avoided potential consumerist shallowness. The choice range was wide: from Hollywood entertainment, through European children's film genre, East Asian melodramatic sensitivity, and eventually politically-oriented European scene. A great melange that generates huge expectations for each title in the programme. Awarding European films was not intentional but resulted from the jurors' attitude that combined excitement with necessary critical distance.

There is no way one can say “No” to the invitation to be a jury member at Animafest Zagreb. By the festival's very name, it is a comprehensive review of the most intriguing trends in world animated film. Having an opportunity to evaluate any of Animafest's competitions is not only a privilege and a pleasure but also, to the modest and realistic extent, a responsibility towards animated film aficionados. In a long-term perspective, festival verdicts (along with everything that has been either acknowledged or overlooked by the jurors) contribute to the canon-building process, thus influencing the history of filmmaking and spectatorship.

By the time that merry pictures will disappear from social media, the choices and explications will remain accessible in various forms of festivals' archives, serving as guidebooks or starting points for a revisionist approach of future filmmakers and researchers. It is a small field of cultural industry that remains prominent even if it bears symbols instead of profit. To cut a long story short: recognition of Animafest 2018 feature film competition programme through explications of the jurors (among them the author) provides just tiny bits of what can be discussed regarding the awarded films. Often, the explanations are merely the average results of stylistic, thought, and emotional expressions shared by a diverse group of people. But if you have an interest in finding out more, I am going to expand the scope of reflection we have discussed in jury meetings with Joni Männistö and Arsen Anton Ostojić, naturally speaking solely for myself, awaiting comments and/or criticism.

Fantastic Team of Mr. Anderson

Isle of Dogs is a spectacular animated movie. A heartbreaking fact for an incurable cat lover like the author. Only after the verdict meeting did we experience Kim Keukeleire's masterclass, a calm and in-depth study that took us step by step through the process of brilliant animation filmmaking execution. One can only admire perfection of puppet design (great piece on Andy Gent's and his puppet-builders team can be found on awn) and attentiveness applied to its smallest details that provided these animated creatures with individualized screen persona – achieved through let's say Atari's glam-silver suit or dogs' fur almost tactile softness and tenderness. The background design is filled with masterfully sculpted artifacts, and apparently, the designers and craftsmen have reduced the illustrative excess of the storyboard. The cinematic tensions, conveyed through camera movements and reflected in character and spatial relations, should also be praised. And yet a striking fracture marks this otherwise impressive creation.

Wes Anderson is a magnificent jester who keeps telling ironic fairy tales about a post-postmodern individual confronted with a cruel maze of social interactions and havoc of personal crises. But presumably Anderson does not believe in anything other than mockery and illusion. His game is sophisticated but escapistic. Do I care about the tensions the director has created, such as Atari's solitude or the American students' revolution? Following the rules established by Anderson, I am concerned with the net structure of gazes, gestures, and bodily movements, as well as the mapping of the labyrinth that determines storytelling, or dissecting the auditory games played between dialogues, voice-over, and sound design. I endorse this film as long as it is an intelligent subject of analytical exercise, yet the interpretive efforts unveil triviality and that is a short-cut to indifference.

If you are a cinephile who loves Wes Anderson because of his consolidated style and courage for remaining essentially predictable despite of multitude of creative ideas implemented in the various cinematic worlds he has created (check this great Wes Anderson's 'reader' below) you will be more than satisfied with Isle of Dogs. But if you are called to name the freshest, inventive, touching, and eye-opening film in the programme, you will be content with the entertainment provided, but eager for further challenges.

Laughter and Despair

The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales (Le Grand Méchant Renard et autres contes, 2017, dir.Patrick ImbertBenjmanin Renner“Zippy Frames” reviews the film, it was clear that this one is the audience's favorite. Non-stop waves of laughter of kids and adults alike lasted throughout the whole projection. It was interesting to observe how the formula of amateurish theater/cabaret has been successfully translated into animated film language. Loosely connected three episodes derive from an ever-fruitful strategy of social satire: ignorant and rebellious ones demolish the stable lives of those who are prudent, all of them are good-hearted, though, so be sure that the conservative status quo will be brought back. Nothing sells better than baby/house-building/Christmas-themed stories.

Another most pleasurable proposition for young audiences is Kaspar Jancis' Captain Morten and the Spider Queen(2018, read more here). Unfortunately, it does not seem to meet high expectations the viewer might have towards the Nukufilm label (though it should be noted that the film was co-produced with Irish, British, and Belgian partners). While watching the film, it is necessary to make peace with the notion that Estonian production is not bound to possess a subversive undertone, mind-twisting narrative resolutions, or any other kind of surreal triggers. It is a straightforwardly charming fairy tale, realized with huge dedication and care towards visuals (behind-the-scenes details below) – take it or leave it. “Plenty is no plague” does not apply to filmmaking, though, especially since this strategy does not work in script-writing. In a film, we experience a huge variety of young Morten's adventures, he is constantly whirling, struggling, drowning, winning, losing, flying... Everything is fast-paced, but the segments of the story seem detached from each other; they add up to astonishing visual entertainment but do not really develop narrative changes that would stimulate the viewer's curiosity in story-following.

The Asian productions were sadly the weakest titles in this race. Taiwan/PRC co-production A Dog's Life (Gougou shangxin zhi, 2017, dir. Yi Chang, watch an excerpt) unveils four episodes in four different CGI techniques and an unbalanced storytelling structure. Starting with a story of an abandoned puppy, we move forward to the stray dog character whose nature doesn't allow for any attempts at domestication. Further, we witness an intimate drama of the descent of a small and somewhat irritating pet doggy being under the care of a senile widower, to be eventually surprised with one more take on the problem of dogs' submission to their human masters, this time, the sterilization issue is discussed. The film employs various methods of CGI creation – from hyper-realistic 3D to flat and, in a way, superficial digital cut-outs. Given the examples of A Dog's Life and The Big Bad Fox..., it seems quite apparent that the animation filmmakers have to reconsider the idea of joining loose episodes into a feature, for this formula does not guarantee convincing comprehensiveness.

The Shower (Sonagi, 2017, dir. Jae-hoon Ahn and Hye-jin Han from South Korea stand for another risk in filmmaking endeavors. It is highly consequent in its subtle visuals depicting the slow beauty of the earthly evanescence of an imaginary rural landscape. First love is interwoven with the tragedy of the first encounter with death. As the starting credits say The Shower is an adaptation of one of the most valuable Korean piece of literature, Hwang Sun-won's “Rain Shower” ("Sonagi", 1959)And so while watching the film I have pledged to myself that one day I will read this novel and find out if I am right to think that The Shower kills the idea of an adaptation as creative treason, for its tempo, metaphors and narrative flow seem to belong to some other medium than animated one.

Top Three

Crossing out children's films, spectacle, and melodrama, we are left with three works that can be labeled as cinéma d'auteur. It should come as no surprise that these are European films. Only one of them (Grand Prix winner, This Magnificent Cake!) was realized in the EU-promoted co-production model. And only one of them (Cinderella the Cat, omitted in the verdict with a heavy heart) is in fact a full feature since the rest falls into (non-existing in competition regulations) category of medium-length films. Obviously, for this reason, This Magnificent Cake! and The Man-Woman Case (Special Mention) have no chances to make it into the contemporary distribution market. Regrettably. If you have the opportunity to watch these films, don't miss them!

These top three works are the most different films, addressing diversified targets with varied agendas and atheistical means. Anaïs Caura's The Man-Woman Case leans towards current discussion of gender-based oppression, reviving the forgotten and ambiguous hero of transgender history. Reminiscent of Jean Genet's vulgar-saint, Eugene/Eugenia Falleni is deprived of human dignity as a subject of rape, hate speech and lynching. Simple drawings transgress between intimate visualization of the mental struggles the character experiences throughout his whole life, and strip-like portrayal of the lowest surroundings of the 1920s docks.

The main character, a runaway accused of brutal murder, lacks almost any facial features except for the red scar, but throughout the film, he is repeatedly called “The Man with a Thousand Faces”. With the exclusion of a few supporting characters, the crowd that surrounds Eugene also lacks distinctive identity marks. It is a simple, almost banal authorial trick, yet it bears the power to universalize Eugene's story from a particular historical trivia to a wider reflection on problems crucial for the contemporary debates expressed around the world.

Cinderella the Cat (Gatta Cenerentola, 2017, dir. Ivan Cappiello, Marino Guarnieri, Alessandro Rak, and Dario Sansone is a stylized and disturbingly unreal 3D musical woven from various pop-cultural threads. The baroque atmosphere evokes a style akin to Baz Luhrmann's cinema, characterized by excess, kitsch, and melodramatic cultural critique. The convention of the Cinderella tale is just an excuse to shape storytelling after recognizable motifs and twists, but if you are highly attached to the story's traditional developmental line, you need to be ready for disappointment. Cinderella character does not matter much here, glass shoe turns out to be a perfect vessel for cocaine trade, Prince Charming is just a nickname given randomly to a certain special agent and anyway, an alias that is soon forgotten, moreover there are two villain kings whose ambition is to dominate the criminal underworld of Naples after ecological and moral apocalypse.

<p">

Somewhat monstrous and exaggerated female characters seem to originate from modeling based on cross-over between Disney's princesses and Jessica Rabbit's sisters; further, they are subjected to anime-like transformations, with big eyes, emo haircut, cheap sex-appeal, and above all, unbelievable bodily flexibility exposed from most surprising angles. This kitschy and claustrophobic dystopia is inhabited by the holograms of past occurrences, and its borders are delineated with the corroded steel walls of a ship that disintegrates in front of our eyes. It is a world of no hope, since the only rescue for the oppressed mute teenage Cinderella is delivered by a loyal servant of a long-gone Godfather-like patriarch.

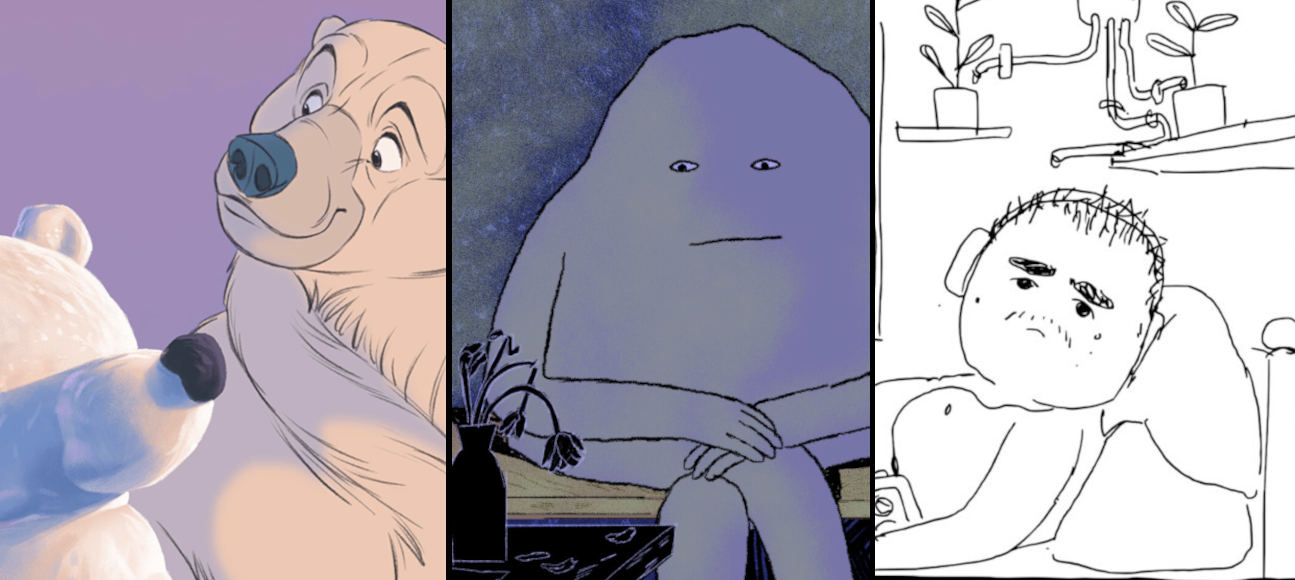

And then there came a cinematic revelation.This Magnificent Cake! (Ce Magnifique Găteau!, 2018) by Emma De Swaef and Marc James Roels is a film built upon the structure of seemingly disconnected episodes; however, the authors have sketched the story with mathematical precision. Each action, movement, the simplest gesture matters for the story's development. Nothing happens without consequences. As in the famous short Oh Willy (2012), the authors create the world from woolen artifacts and fluffy puppets. This material creates an atmosphere of intimacy and safety for the set and surroundings, while the characters remain grotesque, clumsy, and doomed to misery. The impression of safety appears as the greatest fake since the presented world reinterprets colonial imagery with symbolic sets of a jungle, a dirty steamboat, and European architecture disrupting a vast African landscape.De Swaef and Roels have an inclination towards combining animation filmmaking with psychoanalytical reflection, but they do it in a sophisticated and non-intrusive way.

Certain narrative motifs occur in their works: characters enter the hidden unknown, stray in the forests, and indulge in obscure sexual acts. This Magnificent Cake! touches upon the problem of evil that is inseparable from primal human drives. In a direct way, the film focuses on the dark side of Belgian imperialist history and its totalitarian conquest of Congo. The story starts with a surreal sequence of a pathetic king's insomnia resulting in the tyrant's decisions to invade the land in Africa (read Vassilis Kroustallis' review) and to fire an old clarinet player from the royal ensemble. In other episodes, we follow the disintegration of humanity and the morality of the bourgeoisie merchants juxtaposed with the loss of integrity and death of those who are powerless – enslaved indigenous people or the deceived European poor escaping injustice and military oppression. The heart of darkness is pulsating and it absorbs each and every soul possible, making them accomplices in the reign of terror. The expressive force of This Magnificent Cake! relies on perfect use of cinematography and corresponding set lighting, both invalidating the mediatic borderline between animation and live-action. Similar cinematic thrill occurs within a projection of Isle of Dogs, but this time the silver screen demands the viewer's attention, grief, anger, and awakening from sweet dreams of illusionary pleasures.

Future is Now

It so happened that (subjectively) the best three films come from Europe. This interestingly corresponds with the fact that European culture decision-makers currently prompt the changes in regard to production and distribution priorities, especially in the case of features. The identity of European animated industry is a subject of already ongoing discussion and so far it seems that the prominent studio executives and EU grant system operators favor contemporary global/Hollywood model that marginalizes artistic experimentation, intellectual tensions and cultural revisionism for the sake of satisfaction of an illusionary average receiver that supposedly seeks audiovisual entertainment more than inventive attractions, and cinematic pleasure instead of identification challenges. Apparently, Animafest's verdict does not support this tendency. Just-concluded Annecy 2018 similarly does not refrain from appreciating European animated cinéma d'auteur>. Now, the question is whether the authors and their producers will be able to translate this symbolic arsenal into means of production, since, naturally, the currently occurring transformation of the market and industry is of a pragmatic and transactional nature. If the artistic integrity is supposed to remain a cherished product of the European market, the animation community should collectively figure out a reasonable and valuable enough replacement currency. Otherwise, we risk an inevitable boredom of consumerist culture that imitates art.