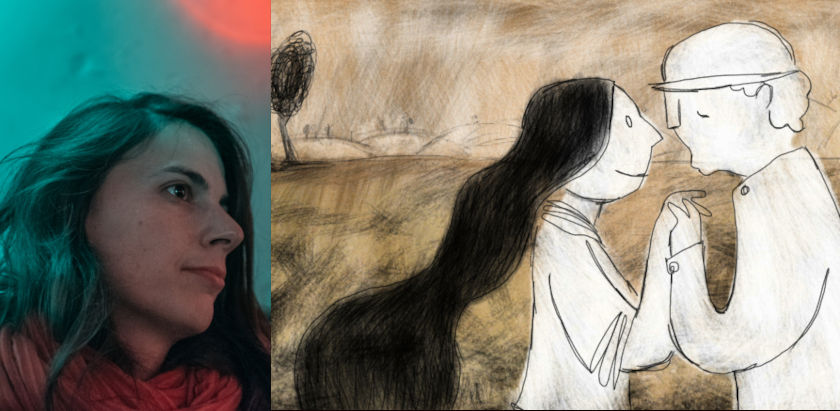

Getting to the Image, Getting to the Story: Interview with Marina Rosset (Swiss Animation Portraits 2022)

In 2005, ‘After a Cat’, a little, student film from the HSLU (Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts) made it to the programs of widely acknowledged festivals such as Anima Mundi (Rio de Janeiro), Molodist IFF (Kyiv) or Krakow Film Festival but also to Tricky Women in Vienna, back then a four-year-old “fresh-woman”, soon to become the most inspirational European spot to observe and empower women animators. This situation might be a fitting metaphor when speaking about the artistic creativity of Marina Rosset, a modest animator with great success, constantly challenging herself with new ideas.

Rosset’s animated worlds appear stretched between what can be conventionally expected and what is intentionally hidden. She is interested in tensions and emotions occurring in between. ‘After the Cat’ is a somewhat creepy but also a hilarious anecdote about a husband and wife (two monsters) who live their routine life (one obsessively kills cats, the other one turns into a zombie), while the distance between them becomes unbearable. Rosset worked on the film as a director, animator, cinematographer, and editor – and that’s one another characteristic of her work: being a solo player. Mixing techniques complement the set of distinctive features of Rosset’s approach to animation. When perceived against the background of films she made later on, ‘After the Cat’ presents the most abstract and definitely the rawest stylistics – and yes, changeability is one more quality found in Marina Rosset’s films. The fact that Rosset not only changes tools and techniques but also the styles and aura of her films becomes one more specific feature of her artistic persona. Marina Rosset went a long way from this early, student humoresque, nevertheless, she has remained truthful and consistent with herself and her own artistic temper.

Rosset recalls: “At first, I was interested in drawing. I was more attracted to comics than animation, but I feared I did not know how to write a story. So, I chose animation, thinking I could then draw a lot with very little writing.” She embarked on studying at the La Cambre school in Brussels but after only one year she came back to Switzerland. Rosset enrolled at the HSLU, one of the most recognizable art-house animation schools in Western Europe.

She recalls her ‘uni years’ (2004-2007) as times of freedom and experimentation. “In Belgium, the curriculum was basically: every year each student makes one film. That's it. No formal teaching of animation technique. I felt a bit left alone at first, but it taught me how to create something without waiting for someone to tell me what to do at every step. In Lucerne, the animation degree was just starting over there. And since it was not that formal, everything was still very free, I could do what I wanted to do, if I wasn't interested in an exercise, then I would be working on something else. That’s how I could make one short film every year (just like I would have done in Brussels)”.

La fille aux feuilles (shooting)

At HSLU, she had occasions to consult her ideas with Paul Bush (e.g., ‘November’, 2006). Rosset is neither avant-garde nor experimental provocateur. Regardless, she is quite capable of finding her own voice even when challenged with purely experimental tasks.

In 2014 Paola Bristot (director of the Piccolo Festival dell'Animazione; animation and comic arts curator) called a group of 10 brilliant European animation artists (among them Špela Čadež, Regina Pessoa, Ülo Pikkov), including Marina Rosset, to pay tribute to Norman McLaren’s non-camera animation and visual music explorations. Rosset’s segment in the ‘Re-Cycling’ omnibus, demonstrates the elusiveness of sharp objects with rugged textures (such as keys or stamps) which can smoothly integrate into white background.

At the HSLU Rosset created two more, rather light-hearted films that twist and mock the storytelling’s conventions. Certain patterns that were recognized by Vladimir Propp are frequently implemented by many animators, filmmakers, and writers as if they were fundamentally unshakeable truths. However, ‘Botteoubateau’ (2007) and ‘The Bear’s Hand’ (2008) do not pretend to be something else than smoothly animated audiovisual jokes.

‘The Bear’s Hand’ revises the pattern of three brothers facing a unique challenge and the third one achieving greatness, aided by a helper. One day the youngest brother (who is reluctant towards guns and easily gets scared) has to replace the oldest one in his daily obligations and… Well, not to make any spoilers but the film’s bottom line (“Maybe tomorrow you will meet again your friend in the forest”) is bitter and perversely grotesque. Rosset’s style starts changing at this stage, leaning toward the forms she is most well-known for today. The textures in the background are not yet that vibrant and twitchy but the character design starts combining realistic conventions (especially in regard to the costumes and other details) with arbitral, freely improvised styles of representation when it comes to characters’ contours and shapes as well as the dynamic of the characters’ interactions with and within the environment.

In “Laterarius” Rosset achieved expressive stylistics by combining 2D and hand-drawn animation. The vibrancy of lines and contours as well as the sketchy shaping of the figural elements in the composition add up to the impression of observing graphic artworks set in motion. She relies on her intuition and allows the images to dictate their own terms of visual development. Naturally, such kind of liveliness of imagery cannot be free from blurs, smudges, or other imperfections. In Rosset’s view, these kinds of mistakes may sometimes elevate to qualities: “I start with still images. I like when they’re not perfect as if they weren’t meant to be perfect. I spent a lot of time testing and animating the scenes I’m sure will be included in the final cut. In the end, the technique is always changing, some parts don’t match anymore. There’s a lot of material to be thrown away but I keep the mistakes I like.”

Laterarius

Laterarius

When asked about her approach to storytelling, Marina Rosset says: “At first, I was scared of it and now it’s something that interests me the most. There was no breakthrough moment though, but a process of making one film”, then the other one, and saying: ‘Oh, this is interesting; this I have to learn; how is that going – this works, that doesn’t…’”

“The seed of the story is in the drawing,” Rosset reflects. The process of creating animated visual narratives begins for her with finding an idea and enclosing it with an image. This idea has to be so captivating that she would be willing to stay with it for years. Apparently, when Marina Rosset says “‘It is all about working a lot” she actually means this literally. Production of ‘La fille aux feuilles’ (2013) took three years while her newest film, ‘The Queen of the Foxes’ (2022), was in production for six years. Testing, animating, making quality mistakes – all these are devices that enable arriving at unique stories. Rosset lets them be driven by their inner flows; slowly but smoothly she keeps searching for their best possible visual representation.

Marina Rosset’s most successful film so far is ‘La fille aux feuilles’. She recalls: “At that time I wanted to do a project that would please me aesthetically. I wanted to work with oil and pastels. This story was built around an image – the leaf swimming in the aquarium. I built the whole story to get to that image.” From a meaningful but tiny element of imagery, Rosset created a story that is at the same time peaceful, disturbing, and sensual. Eternally conflicted powers, humans and nature (embodied here in the characters of a melancholic boy and evanescent, blue-haired forest nymph) attempt to resolve these everlasting tensions through sexual passion.

The feelings are irresistible, and the desires will be fulfilled, but inevitably, they will drift away from each other. The dim hues of brown, red, yellow, and blue bring visual comfort that reduces the tensions. The viewer is right to contemplate the beauty of the details rather than impatiently awaiting the story’s climax and resolution.

The international viewers will have an opportunity to watch ‘The Queen of Foxes’, Marina Rosset’s latest film, at Annecy 2022. It was screened already at Oberhausen and Berlinale. It is being selected for the children’s film programs but targeting kids and youth was neither any intention nor a pragmatic production decision. In fact, the film resonates well with both young and adult audiences. This can be an example of “labeling” – a somewhat problematic but sometimes unavoidable situation that many animators have to deal with.

Rosset admits: “In the case of this film the spark that got me started was that I wanted to have a happy ending. I was working on different things and I came back to some earlier unfinished stories (I have lots of them), I found one that I wrote in 2007, when I was terribly lovesick, back then it was a very sad story. This time I decided to try and let every character have their happy ending, I put some new elements, and it worked.”

It is surprising to discover this personal and somehow traumatic “back-story” behind such an uplifting finale. The delivered storytelling is gentle. The choreography of animated movement and transformations is skillfully condensed while the characters of foxes are sophisticated yet also strikingly cute (the children’s audience in Oberhausen was genuinely right to state: “We thought the animation in this film was especially beautifully drawn, and the foxes looked quite real”). All these combined with magically misty scenography of the forest and sleepy town inhabited by lonesome lovers, presented in a delicate color palette, sync together in a visually most pleasurable way.

Marina Rosset is a solo player, virtually in all her films she takes responsibility for the most significant tasks in the animation filmmaking process. Working with others may be of course fruitful, but “organizing and communicating also takes energy”. Nevertheless, there are certain artist-friends whose names keep recurring in the credits of Rosset’s films, above all Jadwiga Kowalska and Maja Gehrig. There is one more creative practice, highly very important to Rosset: “A lot in the development process is done through telling the story to other people, to see if they are interested or maybe they stopped listening. I tell them parts of the story before it’s finished. I don’t really know what’s to happen, where we’re getting. I do this to fill the holes in the story.”

When asked to characterize the Swiss animation scene, Marina Rosset points out the creative diversity and availability of appropriate funding for a short film. Focusing on Marina Rosset, her films, and her artistic persona, but also keeping this greater picture in mind, one notices that in Switzerland an irresistible creative potential explodes from a combination of laborious work and mundane life situations that may bring out an unexpected beauty straight in front of our eyes.

Marina Rosset atelier

The Swiss Animation Portraits 2022 series is conducted in partnership with Swiss Films.

Contributed by: Olga Bobrowska