Interview: Steven Woloshen and His Cameraless Film Memory

Scratch, scrape, hand-paint, glue: a world of things you can do with the film without actually shooting. When these things also become artistic, here's Steven Woloshen.

The Montreal pioneer of experimental filmmaking and animation invests over 30 years in cameraless art with 16mm/35mm film, and now digital tools in addition. Music and jazz soundtracks are the indispensable tools of those shorts, the bread and butter of Woloshen, who makes his films dance to the rhythm of swing, bebop and sometimes to the guitar riffs of Jimmy Hendrix.

Calling himself a frugal filmmaker, Woloshen is also active in the publishing department, with Recipes for Reconstruction and Scratch, Crackle and Pop! complementing his teaching work in many film and animation workshops around the world.

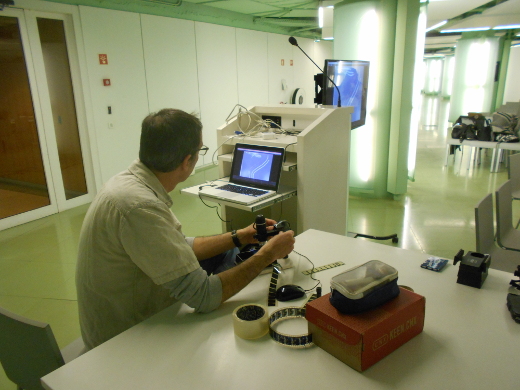

We met Steven Woloshen at the 2016 Monstra Animation Festival, where a retrospective of his work was being programmed.

ZF: I was really impressed at the way your films were presented at Monstra Retrospective. Sometimes even 60 minutes of narrative animation can be boring, but your programme of experimental film did not look boring at all. Did you programme the films yourself?

SW: I've been playing with the dramatic flow of the programme for about 10 years. What I'm trying to get across is the diversity of the films and, at the same time, keeping the interest of the audience alive. It can't be more than 60-65 minutes to satisfy both requirements.

ZF: Do you work that way when preparing a single film?

SW: It's the same process, for I think of the next film how it fits in the framework of all my earlier ones. I don't think in terms of award-winning films, competition or panorama sections. Each film has a work flow that needs to be explained. It is the teacher in me who has to use it as a future reference. If you write a book, you want a chapter in the book to mean something, to be quoted, to be referenced for somebody else. If you think it's hard to make a film, it's even harder to imagine how to fit in the framework of all other films. That's the puzzle.

ZF: You really work with the conception of the auteur here, the creative filmmaker who's responsible for every creative aspect of the filming process, and references eariler works in the process.

SW: I learned a lot from Stan Brakhage's work, and that his life was annotated as a series of films. By watching his films, you would get an impression about the man and what he stood for. What I'm trying to do with each film is to creat a snapshot of myself at a certain time, and then see how it fits together with the rest. This is my world philosophy: my films, along with my interviews and books, reveal the truth about me.

ZF: You constantly press the question of artistic freedom and creativity. How free were you as a grown-up kid in Montreal?

SW: I had the freedom to do anything, there was no pressure or end result. My desire to be a filmmaker evolved when as kids in the suburbs we were destroying and burning a lot of things. My parents cherished their home movies, so this is was my first target to go after. We were very entertained by scratching and scraping them, adding sound to them and running them backwards and forwards, then burning them. And we were soon making movies destroying other people's property.

My natural habitat was not found in the cinema's screening rooms, but in the projectionist's room where I could sneak in (without paying a ticket) and find footage; in the trashcans and dumpsters, where people didn't belong and they were not welcome; we were kids of the punk/rock era, trying to find flowers in the dustbins, and skipping classes we were meant to attend.

ZF: How do you feel today that cinema is taught as an academic subject in the Art Schools and Universities?

SW: I think that somehow academia squeezes the life out of cinema. People who are academics, not practitioners, usually teach it. At Concordia University, I had the opportunity to be taught by both practitioners and academics. I've seen a lot of academic talk about my films, but these people don't have a clue how I did it. They write about it, they assume I took my computer and mixed things up and added a soundtrack, and that's totally wrong.

ZF: But your own films have evolved as well. From using raw film material and then project them, you know combine actual film stock and digital techniques. Was it a conscious choice or the evolution of the film left you with no alternative?

SW: It was a conscious choice. Films are hard to get, but I want to have the technique of today while working with the film of yesterday. I don't loathe the digital, I want to try and be able to say, "yes it works/ no, it doesn't work with this kind of film I'm making".

ZF: So, you think the question of the analog vs. digital is a false question.

SW: Yes. My work is exactly the same as with people who paint on paper and then digitally capture it. Now, I know there's a lot of academics who are trying to generate this debate, but they do not understand its terms. The debate about how the future of film, film labs closing and reopening, this division between your scratch world over here and the super-digital Hollywood production over there is just not true: the people who generate those questions do not live in the same world as I am.

ZF: Is it difficult to live in your world?

SW: It's easy to live in my world, for it is what I make of it: the people I meet, the conferences I attend. I don't have to live with the pressure and expectations of an animation studio be upset of what I'm doing.

ZF: Two of your films are quite unique: I'm talking about The Homestead Act (2009) and Crossing Victoria (2013).

SW: Crossing Victoria is part of an ongoing project stretching over 10 years of time, constantly evolving and interpreting in many different ways. The documentary is about me crossing a bridge (and a national monument) on a snowy night in 2004. The memory of that night walking on the bridge was very dramatic, but I wanted to see what I can do artistically with that.

RH Factor (2008), Zero Visibility (2009) preceded Crossing Victoria, and they were all reinterpretations of the same incident, but the latter was the one for which I first got the grant to get it made.

I had 3 years to think about it (started writing about it in 2010) rather than respond to it spontaneously, and this really changed my workflow Unlike my other films, I had the image first, and put the sound later (also used digital compositing), so I needed to focus on what the image meant to me. I'm trying to abstract a specific memory, so that it somehow becomes the memory of a film about that very same night. I'm also answering a technical question here: can you project images onto film? Can you shoot a projected image onto raw stock film without a camera? That's what I did.

The Homestead Act talks about the two aspects that I want to build on, decay and resurrection. The Homestead Act was the film that provoked me to write my first book, Recipes for Reconstruction.

Homestead Act, Steven Woloshen

I found a 28mm film in a photo shop and made a loop of it. I photogrammed that loop, wanting to create the experience of an abstract film that started off as a cinematic representation. The Homestead Act is the third part of a larger film, which I haven't done yet, a sort of a history and archaeology of film and the world. It's all about soil and nature. I do like archaeology: it's like trying to look at the film's future from the past, like a Hollywood classic who's now decaying, and gets a new life in this work.

ZF: Where did you get the footage from Two Eastern Hairlines (2004)? It looks like a Hollywood/TV drama of the 50s.

SW: That was from a Swiss film of the 50s. What I wanted to do was to take the human interaction and re-write the story. I had no idea what the story really was about, but I tried to reconstruct it visually. That's part of who I am: taking isolated bits and trying to figure out how they could have fit together.

ZF: What would your world be like if there were no music?

SW: I guess I'd just have to sync my film to the rhythm of the projector [he laughs]. Using music is part of my optimistic view on filmmaking. and I'm using a lot of music in my work.

ZF: Do you think that the distinction between animation and experimental film is useful?

SW: It has no value. These days people are really enjoying making hybrids of formats, like animated documentaries. Classifications are pigeonholing and crippling. I really enjoy the experimentation of Len Lye and Norman McLaren, but I wouldn't like to live in their period. What I'd really like to do today is to travel between many places like Argentina or Morocco and new places where there is the spirit of discovery these guys had in the 30s and 40s. To find a place where that Len Lye spirit still exists.

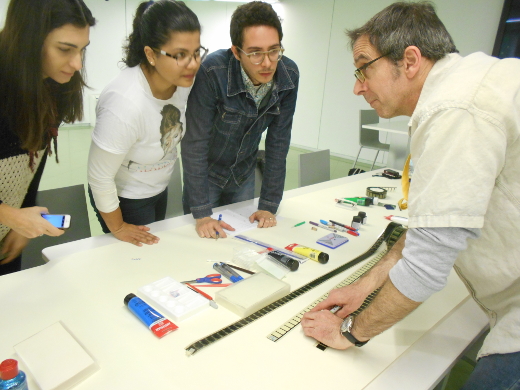

Steven Woloshen, MONSTRA 2016 Workshop

I even hope that organizations like The National Film Board of Canada will keep doors open for people with new ideas through co-productions in continents and countries like Africa or China, which have very talented people.

ZF: Digital has made students and young artists more confident about their own work. Can you predict the future of independent animation regarding promotion of the artistic work?

SW: I think the biggest direction for independent filmmaking to follow is for people to go online. Vimeo channels and social media is the testing ground for all who aren't sure they've got an award-winning film, but at the same time they don't want to be afraid of experimentation.

People create loops and gifs online, and that's how far it's going to take them. It's hard to go to a cinema and present a 8sec film, but for people who want to put themselves out there (but don't want to be judged for it), social media is the choice.

ZF: You've written two books so far, Recipes for Reconstruction and Scratch, Crackle and Pop!. Are you preparing for a third? What is it about?

SW: Found footage. It's about the realities of other people's films to make your own. Finding those films in the most unexpected places, and what you can do with that.

ZF: What are your favorite directors?

SW: I like Jacques Tati's Playtime (1967). It was the biggest gamble in French history, to build a complete city from scratch. The film was the epitome of the decentralized gaze. That's when you can't focus on a single point in the artwork, but your vision is focused on a thousand of points.

I can't say that I cared much about the comedy, but the decentralized gaze is for me what Playtime was. It employed a big frame where everything was in focus.

Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is another favorite, probably for the same reason. I like narratives that go wrong, fragments that do not fit together, the deconstruction of something after it has been constructed.

I like anything where there's derailment; Len Lye was the first to do that, and the Dada and surrealistic films did that as well. I love all of that.

I love the work of Bruce Conner and Joseph Cornell, another found footage filmmakers that I want to study. And I fantasize that Dziga Vertov was trying to make a found footage film, but he didn't find footage to shoot, so he shot it himself

ZF: Your films are playful but also strongly political

SW: It's funny how art movements reflect the world we live today. Obviously, The Homestead Act is very political for me, and Dada and surrealist films are all about politics, democracy, and individuality.

The Babble on Palms (2002) was my 9/11 film, actually made the day after the event: I was watching the news, and people came up to the camera. They were showing pictures of their loved ones in their hands, asking if anybody had seen them.

The Babble on Palms

I asked this question: what if your hand was everything about you? When you put your hand in the camera and say, "this is me", each hand becomes like a mandala symbol, unique for each person and unlike anyone else's hand.

ZF: What are you planning next?

SW: I have four films projects. I have a grant from the Canadian Council of the Arts for a new film. This will be a lengthy process, starting from the image and then the sound design. I have a number of photogrammed films, basically putting light on found footage on the raw film stock.

ZF: Do you think that animation festivals serve their purpose?

SW: I like it when the center of the festival is the guest and the experience of meeting each other. I think that's what a festival should be. When it's about award or promotion, I think it falls apart.

Annecy is fine, but I'm more a big fan of Animafest Zagreb. I like all of us being together in the same place for a week, seeing each other over and over.

I am a big fan of Punto y Raya festival (PyR), a travelling festival. I'd rather go to places I've never been before. I've never been to Portugal, so I' really like being here and seeing Lisbon and its Monstra Festival.

ZF: Steven, thank you so much for the interview.

SW: Thank you too.

.