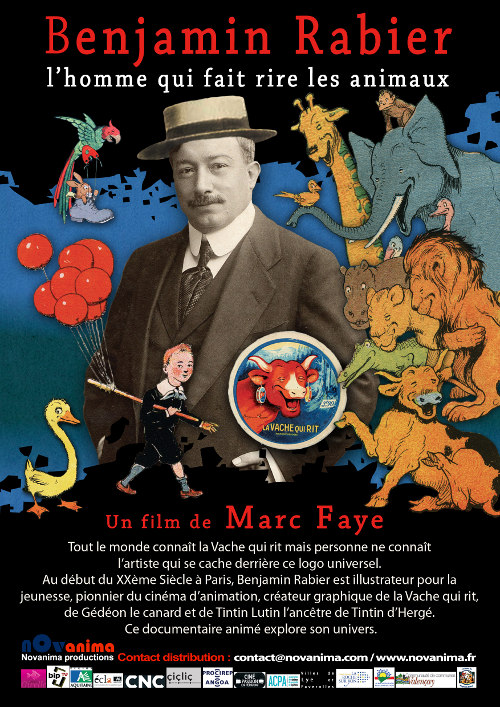

Benjamin Rabier review: The man who made the animals laugh

The French illustrator and animator Benjamin Rabier (1864-1939) is not readily discussed in the history of animation, even though he collaborated with the French genius Émile Cohl in a number of pioneering (but lost) animated films.

His public perception rests especially on the clever ad of the Swiss cheese company Fromagerie Bell, the laughing cow (La vache qui rit) back in 1924 (even though Rabier's drawings had premiered much earlier, during the WWI). But Rabier did not make only the cow laugh, but a lot of other animals.

The new documentary, Benjamin Rabier: The man who made the animals laugh (Benjamin Rabier: L' homme qui fait rire les animaux) by Mark Faye and Novanima Productions promises to change this conception. This film designs a linear trajectory from Rabier's humble and poor origins to his rise to popularity in 1910-20s (he was awarded the French Legion of Honor in 1913), land also leaves time for a severe incident of mental breakdown.

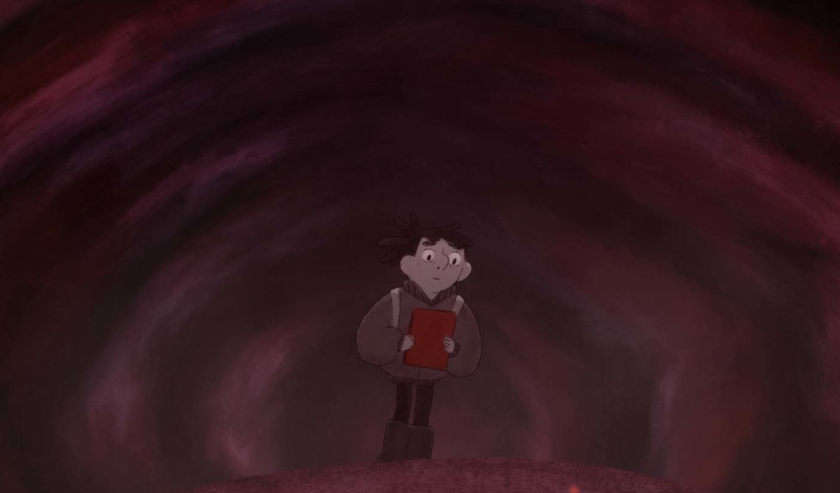

The first, animated minutes of Benjamin Rabier work as an establishing shot, with cut-out figures in Parisian market, where Rabier worked at night as a city inspector for almost 20 years.

Human environment is clearly not Rabier's preferred plate, even though he never had a pet. What Rabier seemed to admired (starting from his military service library wanderings) was the illustration of animals in "flat, supple colors, with simple drawings".

If this sounds like an early Walt Disney in the making, Mark Faye's film (mostly in live-action) is meant to make that comparison. And, in terms of employment, Rabier devoted his whole life in creating animal characters: Flambeau the dog and the later Gideon the duck are some of his creations. The most famous human character patented by Rabier was Tintin Lutin, a visual precursor of the more noirish Titin by Hergé.

250 illustrated albums for children were made during Rabier's lifetime, and the documentary (mostly in live-action from now on) chronicles meticulously Rabier's achievements, with the help of his biographer Olivier Calon. The most disturbing fact in Rabier's life is not what the early sequences describes as his city clerk occupation and his simultaneous illustrating career.

Rabier seems to have suffered a mental breakdown by illustrating too much, trying to bring Buffon's Natural History (L’Histoire Naturelle) into scientific illustrated completion. Still, the popularity of the laughing cow ad changed all that.

Benjamin Rabier does not spend much time on the celebrated La vache qui rit (or Wachkyrie, a pun on Wagner's Walkyrie). It does not spend much time either on the Émile Cohl-Rabier collaboration on Flambeau animated films. It leaves it as a matter of natural neglect that the creative split occurred between the two men, even though it has been stated that Cohl protested against being uncredited in the animated series.

It is interesting to be informed that Rabier illustrated some darker topics, always in the company of animals. His Gideon the duck series, which was published before WWII, carries darker undertones.

Benjamin Rabier is informative, educational and sheds some light on the life of a man who had a seemingly uneventful life in a very difficult political period. More interviews with fellows illustrators and animators would be a welcome addition here, in order to see Rabier's current place in the history of French and European illustration.

Within its 53 minutes duration, though, Benjamin Rabier does not disappoint as a handy introduction to Rabier's life and work.

Vassilis Kroustallis