Inside Out Review: A Person Is Not An Island

Have you seen the viral card that satirizes Pixar's films: Toy Story ("what if toys had feelings"), Ratatouille ("what if mice had feelings), Cars ("what if cars had feeligs") and then Inside Out ("what if feelings had feelings").

The plural (feelings) is the problem with Pixar's new concept of bringing back family together, directed by Pete Docter (Up).

The many sentiments that parade in the mind of the Minnesota girl, Riley (Kaitlyn Dias), work together to bring happiness in her mind.

Joy, a violet-looking version of Brave's Miranda (Amy Poehler), the ever-down Sadness (Phyllis Smith), and their sidecicks, Fear, Anger and Disgust seem to be ready to tailor Riley's mood to good humour even though they have no access to the Headquarters, where all important stuff is taking place.

But a sudden movement to San Francisco where Riley's parents (Diane Lane, Kyle MacLachlan) are now ready to settle -but not quite so - brings chaos to both the feelings and Riley. And this is where the adventure starts.

Since it is notoriously difficult to keep focus on all those characters narratively, Pete Docter, Meg LeFauve, and Josh Cooley who wrote the script, chose to details Joy's adventures in the world of memory and the mind. This was not a wise decision.

Riley in the real world becomes a puppet and automaton, and her story and decision matter no more to us than whether Riley's mother should have married that fancy Brazilian soccer player or not.

There are more feelings that Inside Out can handle, and by their very nature, Joy and Sadness cannot be anything other than names and function. What needs to save the film is a merry-go-round through the functions of mind.

This is what the film does, but in a very educational (and not very correct) way. Long-term memory, REM sleep, the train of thought become fancy stops to enjoy and feel danger, but not very innovatively. The world of mind is populated by nothing other than Riley's old friend toy, Bing Bong; other characters are only to serve the message: leave out of here and go back to your safe control area. The two worlds of mind and real world never mingle, apart from a (very funny) scene when Joy and Sadness crush the REM routine to the anger of sleep directors.

Yes, the subconscious is once more the place of danger and a prison (and a giant clown) that endangers family values. But even the pleasure principle that Freud advocated is lost here in the face of sexless Joy; the fact that the film is addressed to kids should not make it sanitized (Disney's Snow White fared better in this department).

Full of one adventure after the other, but curiously devoid of laughter, what the film means to show is that joy and sadness need to go together -along with family values. Celebration of family (with the construction of a kitch family island) is crude here - one can only recall the much-love, 15-minute sequence in Pete Docter's Up on marriage and death to sense the difference.

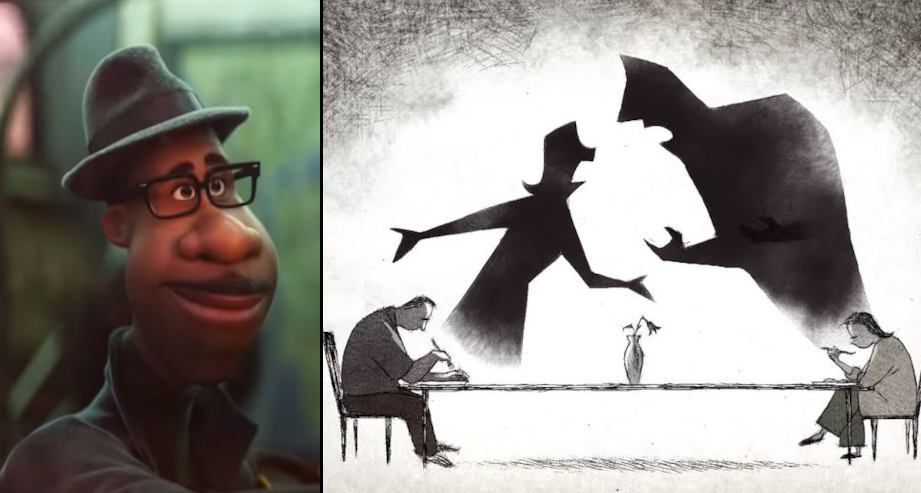

Animation artistry is top-notch Pixar, and the character design of the underdog Sadness easily steals the show. Yet, the film's visual palette is curiously undecided between the eye-candy, extravagant and sometimes dumpy world of long-term memories and the more mundane world of Riley and her family (much preferred, thank you).

Not to mention the affront on 2D animation ("it has no depth!") that Joy and Sadness are obliged to utter when they enter the world of 'abstraction', and animation disintegration. If 2D animation were depthless, none of us could enjoy Disney's predecessors (let alone contemporary European animation).

Inside Out is a menagerie of lights, volumes and consoles. It looks like a videogame into the mind, but never brings a single personality into life, only "personality islands" (friendship, family, sincerity).

One keeps wondering what would have happened if Riley had ignored the many voices in her head and had decided to take that bus back to Minnesota instead.

Vassilis Kroustallis