Animated Multiverse: Review of the Contemporary Swiss Animated Production

Humble masters of past and present, societal rebels and poets of quotidian, experimental mavericks and representatives of audience-friendly industry, acknowledged art schools and low-key festivals... Regardless of one’s approach towards contemporary Swiss animated production, it is a phenomenon that gently but firmly rejects labeling.

Formative Years

“The history of Swiss animation divides into before and after Annecy,” wrote Giannalberto Bendazzi in the second volume of ‘Animation A World History’ (p.197), acknowledging the role of Swiss animation artists and cineasts (among them Gisèle and Nag Ansgore, Bruno Edera, Freddy Bauche) in transforming JICA review into an autonomous celebration of animated cinema known worldwide as Annecy International Animation Festival. Swiss Animated Film Group (Groupement Swisse du Film d’Animation, GSFA) was established as an ASIFA chapter in 1968, and it was soon joined by such brilliant newcomers as Georges Schwizgebel, Daniel Suter, and Claude Luyet whose continuous contributions to this form of cinema elevated Swiss animation to the level of a prominent artistic discipline.

Georges Schiwzgebel’s (born 1944) work should not require an introduction here. The co-founder with Suter and Luyet of G.D.S. studio, up until today he has authored twenty films. In Eituda&Anima IFF 2016 catalog, Paulina Kwas rightly pointed out the most characteristic features of his artwork: “Lack of dialogues, omnipresent music, poetic surrealism based on constant motion, changes of shapes and colors, night dream poetics, a confluence of reality and imagination of dream, as well as expressive coloring, visual erudition, and music sensitivity” (p.97).

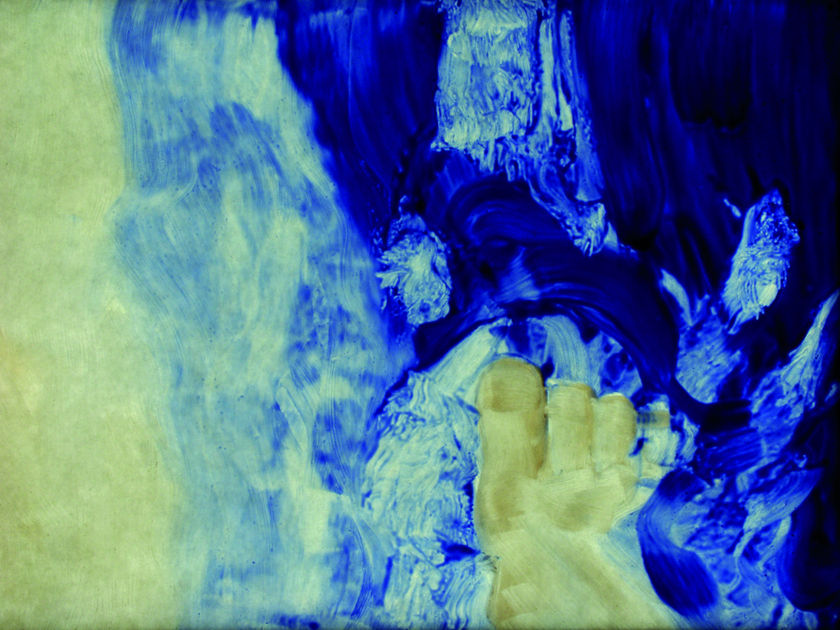

His ‘The Ride to the Abbys’ (1992) is the only Swiss film present in the ASIFA 50/50 Poll (2010), ranking number 35 on the list of world animated cinema masterpieces. Inspired by Hector Berlioz’s ‘La damnation de Faust’, this perfect fusion of images (at points presented in a form of split-screen) appears to be a perceptible record of intangible sensations, blissfully imagined and experienced through the music. The most recent film of this undoubted master of acrylic paint on cells is ‘Darwin’s Notebook’ (2020), a film that has enjoyed wide festival circulation.

Ride to the Abyss, Georges Schwizgebel

‘Lucky Man’ (2022), the newest film by Claude Luyet (born 1948) will be presented in the competitions in Annecy and Zagreb. This engaging dark, twisted, and narrative-driven work rather seems to correspond with the Coen brothers’ sensitivity to the experimental character of Luyet’s earlier films, among them ‘The Square of Light’ (1992). The latter film, made with the pastels on celluloid, positions the spectator as the opponent of a training and fighting boxer, or – as it is eventually revealed – as his mirror reflection. Viewed from a time distance, Luyet’s work may also appear as an anticipation of the VR experience.

Lucky Man, Claude Lyuet

In 1987 Martial Wannaz (1945-2002) directed ‘Douce Nuit’, a cell animation based on 1966’s Dino Buzzati’s novel which conveys the atmosphere of estrangement and which dramaturgically departs from the bourgeois couple's bedtime conversation. Schiwzgebel, Luyet, Wannaz, and Daniel Suter participated in 1987, the Cannes-awarded collaborative project ‘Academy Leader Variations’ initiated by David Ehrlich, which also involved authors of artistic animation from Poland, the USA, and the People’s Republic of China.

Experimental tendencies of Swiss animation are continuously explored by Gerd Gockell (born in Germany in 1960) under the label of Anigraf. Starting from photo and sound collage, ‘Crofton Road SE. 5’ (1990, UK), Gockell’s varied interests elaborated into abstract filmmaking realized frequently in collaboration with German painter Ute Heuer (‘Busy Bodies’, 1990; ‘Patch’, 2014; ‘Not My Type’, 2017) and practice-based research into avant-garde cinema (‘Restored Weekend’, 2004, co-dir. Kirsten Winter; ‘Optical Percussion’, 2008).

Pioneering sand animation artist, Gisèle Ansorge (born 1923; aided by her husband Nag as editor and producer) continued her introspective and surreal filmmaking until 1991 (‘Sabath’), signing the film ‘Anima’ (1977) as a sole director. In the 1990s more women animators have come forward, among them Elena Madrid (born 1967) interested in drawn animation and caricature character design, and Isabelle Favez (born 1974), an author of characteristic love stories and children’s films.

Anima, Nag Ansorge, Gisèle Ansorge

In 2008 Rolf Baechler introduced Swiss animation history to the viewers of the London IAFF and recalled Roland Cosandey’s critical words: “There is no such thing as a Swiss animated cinema, even though it is possible to dedicate a whole book to it. Surely, animated filmmakers do exist in Switzerland, but their work does not bear any other particular national sign except its common place of origin.”

This statement continues to prove right when discussing the most recent Swiss animations. No singular topic, none traits of “essentially Swiss animation school” unravel when observing the animation scene of Switzerland.

The Swiss artists and producers work under very specific cultural conditions – in a country divided into 26 cantons, where 4 languages are considered national ones, and whose political and social system reconciles a strong, confederate sense of locality and self-governance of communities with the concepts of centralized, republican power aligned with the de-individualized, globalized banking corporations.

Here we arrive at the landscape of contrasts, marked by cross-cutting patterns of division and unity. A landscape that somehow resembles a collective film ‘50:50’ (2018, the film celebrated the 50th anniversary of GSFA), or specifically its segment ‘Around the Staircase’, co-created by Schwizgebel, Madrid, and many other animators mentioned further. This short presents ever-expanding, whirling, and surreal composition in which engaging cohesivity is built on aesthetic differentiation and smooth transitions between them.

Strong Characters

Both Claudius Gentinetta and Jonas Raeber were born in 1968 and coincidently the counter-culture aura can be sensed in their films. Jonas Raeber debuted in 1989 with the drawn animation ‘Patt’ which in an ironic and frivolous manner shows the process of transformation of humans becoming items on a military production line, needed only for the self-satisfaction of the conceited general who plays a chess game with an imaginary opponent. In 1991 Raeber established Swamp Animation Studio in Lucerne (active until 2016) where he continued to produce his own works (e.g., ‘Grüezi’, 1995, drawn animation; a xenophobic rant of a “good citizen” – only naturally it is a character of a middle-aged, white male on the holidays abroad) but also provided resources for other filmmakers – among them Gentinetta.

Claudius Gentinetta’s ‘Poldek’ (2004) appears equally related to the artist’s earlier edgy, socially and politically critical, “raw” animations made in analog techniques throughout the 1990s (‘40 Messertiche’, 1990; ‘The Peak of Prosperity’, 1992; ‘Amok’, 1997) but also influenced by the cultural bizarreness and grotesque of Central-East European rapid, neoliberal transformation (in 1995-1996 he was the resident-artist in Kraków, Poland, actively participating in the animation culture life of the city). The 360 rotation of presented images exposes a flimsy tenement building, its backyard, and a few curved streets nearby as the epicenter of the world (oh, how truly Kraków this is!) and a stage of a quite macabre.

Since 2008 Claudius Gentinetta turned towards digital animation tools (in ‘Cable Car’, 2008, he merged 3D with drawn animation; ‘Sleep’, 2010, is a fusion of 2D and drawn animation, while ‘The Islander’s Rest’, 2015, and ‘Selfies’, 2018, were made in 2D computer technique), the themes of his films appear now less anger-driven and more reflexive, while the artist dictates his own terms of production at Gentinettafilm.

Distinct Storytelling

Among the Swiss “natural born visual storytellers” one should mention Claude Barras (born 1973), Jadwiga Kowalska (born 1982), Marina Rosset (born 1984), and Marcel Barelli (born 1984). The latter artist talked extensively to Zippy Frames about nature, reality, homophobia, and other concerns stimulating his filmmaking in June 2021, and a conversation with Rosset soon will be available.

Jadwiga Kowalska has gained international acclaim for the film ‘Tôt ou tard’ (2008). Combining cut-out and 2D computer techniques, she created a highly sensitive but not sentimental, magical tale of friendship capable of halting the natural rhythm of time passing. Sensual and gentle, humorous but morbid, her ‘The Bridge over The River’ (2016) eventually appears to be a love story with a dark twist.

Due to the wide success of ‘My Life as Zucchini’ (Oscar nomination for the best-animated feature), Claude Barras might be the most recognizable Swiss animator. Barras began animating in the mid-90s, and by the end of the decade, he transited from flat techniques to the realm of stop motion animation.

‘My Life as Zucchini’ combines exquisite puppet filmmaking (the production involved a team of nine animators) with a greatly constructed dramaturgy that tenderly unveils a heartbreaking story of children’s suffering (Céline Sciamma, an acknowledged live-action director, co-wrote the script).

Diversity as a characteristic feature of Swiss animation might be related to the frequency and efficiency of collaborations between the artists based in this specifically multicultural country. In this regard, the films of Claude Barras stand for an interesting case study.

The cinematic brilliance of this most acclaimed Swiss animated feature owes a lot to the cinematographer, David Toutevoix. Educated in a fine arts school in Avignon, Toutevoix was a DOP assistant on the feature puppet film ‘Max & Co’ (2007, dir. Samuel Guillaume, Frédéric Guillaume), and later on, he worked with Barras on his “pre-Zucchini” well-known ‘Saint Barbe’ (2007) and Land of The Heads’ (2009). Both films were co-produced by Hélium Films and Canadian NFB, and co-directed by Cédric Louise (born 1970 in Belgium; film scholar by education) who already creatively aided Barras on the production of ‘Banquise’ (2005), a cut-out and 2D that can be seen as a “forerunner” of ‘My Life as Zucchini’.

Soft and supposedly anecdotal, ‘Banquise’ is a story of a bullied girl who searches for a comfort zone in the land of ice (be it Antarctic or inside of a home fridge) but finds death instead. The highly specific character design of Zucchini’s and his friends’ heads (wide round faces, big eyes, enlarged pupils) which were positioned on disproportionately tiny bodies, attests to the innocence of the children’s characters, making further commentary needless. Similar character design appears already in ‘Banquise’, and what’s more, one can also see it employed in ‘Un enfant commode’ (2013), directed solely by Cédric Louise, produced by Hélium Films, made in 2D cut-out technique, and animated by Elie Chapuis whose name is credited in many of Barras’s films…

In fact, attempting to unfold the ramified patterns of collaborations between the Swiss animators, at some point begins to look very much like the work of police detectives who stare at the web structure of interconnections, shared affiliations, and not yet officially confirmed common future projects organized by the “usual suspects”.

Artistic Integrity

Presumably, Maja Gehrig (born 1978) and Michael Frei (born 1987) may be acknowledged as authors most consistently devoted to exercising, upgrading, and redesigning ideas that can be traced to their earliest films. This said it has to be noted that they both look for utterly different, visual qualities in animation filmmaking practice.

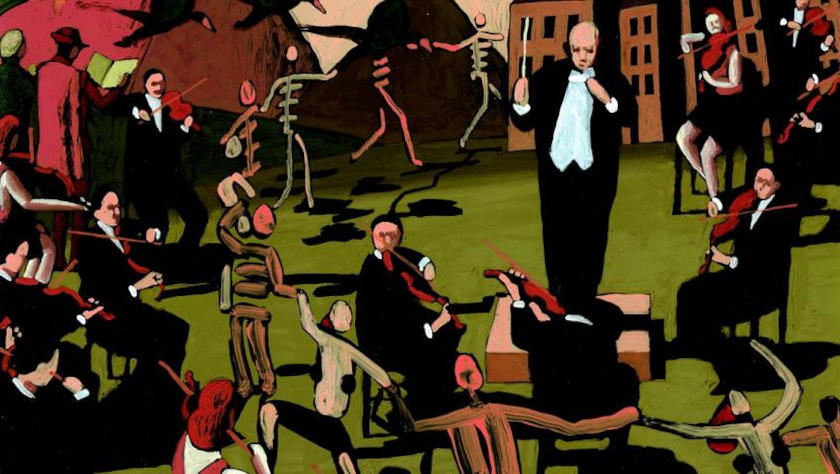

Already in her early workshop experiments (e.g., ‘Metawalz’, 2003, mentor: Bärbel Neubauer; ‘Triple Texas Dream’, 2003, made during the internship at the Eesti Joonisfilm, advisors: Priit Pärn, Maya Yonesho), Maja Gehrig seemed to be interested in the visualization of a recorded data and transformations of mundane imageries as elements of audiovisual synergy. Just recently she achieved a strikingly powerful result of executing this concept in ‘Average Happiness’ (2019).

Average Happiness, Maja Gehrig

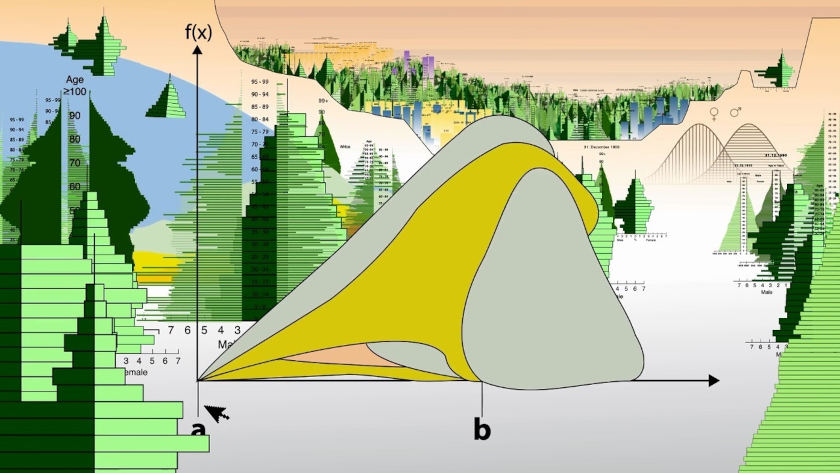

Michael Frei’s ‘Not About Us’ (2012, HSLU / Estonian Academy of Arts), ‘Plug & Play’ (2013, HSLU), and ‘Kids’ (2019), bring out the sensation of watching the same film. This feeling, however, has nothing to do with the notions of boring repetitiveness or the simple continuation of themes and visual motifs.

Quite the contrary. Whenever any of Frei’s films end, one can ask “and what if this humanoid-light switch character would act differently, move to the right instead of left? What if the other creature would submit to the other’s desires willingly? What if they would jump into the black abyss instead of kneeling on a white background? What if…?”…

And Frei reconsiders and reprogrammes his characters, restructures their surroundings, and revises the choreography of their singular or mass movements. Doing this, he does not resign from a set of visual devices that became distinctive for his animation filmmaking – i.e., black and white contrasts, thin and thick contours and lines, multiplications and looping of the imagery and sound effects, sharp and decisive editing.

Plug And Play, Michael Frei

Societal Individuals

Multifaceted experiences leave prints, marks, and scratches on animated images enhanced with the wonders observed in daily life. The contemporary Swiss animators frequently present a tendency to identify themselves as self-aware and to some extent introverted individuals who are at the same time conscious of the greater changes affecting their surroundings. As if they were spotters, they know when to pause, hold breath, and observe.

Such might be the perception of Mauro Carraro’s (born 1984) ‘Aubade’ (2014) which contemplates sunrise over Geneva Lake, or Delia Hess’s (born 1982) ‘Morning Train’ (2012) where a couple intimately entangled during the night, diverge as soon as they wake up.

Samuel Patthey (born 1993) affirms his status as a distant observer – ‘Travelogue Tel Aviv’ (2017) accounts for his personal experiences when studying in Israel, while internationally acclaimed ‘Peel’ (2020, co-dir. Silvain Manney) imagines daily routines at the assisted living facility.

Above all, this notion can be related to the films of Michaela Müller, animator and multimedia artist interested in dance and theatre. Both ‘Miramare’ (2009) and ‘Airport’ (2017) use smudgy aesthetics of paint-on-glass to portray disturbing “non-places” (Mediterranean beach, eponymous airport) where the tourists, emigrants, and refugees interact but never reach out to each other.

Miramare, Michaela Müller

The Personal and the Political

Alike their peers in various countries, the young generation of animators (especially women) open up their visual imagination toward the themes of sexual pleasure, fulfillment, and identity. Student film from HSLU, ‘Ivan’s Need’ (2015, dir. Veronica L. Montaňo, born 1990, Manuela Leuenberger, born 1988, Lukas Suter, born 1986) employs a comical tone in emphasizing the necessity of pursuing, understanding, and respecting different needs of lovers as a means of experiencing euphoric sexual intercourse.

Sophie Haller (born 1985) is quite straightforward in her artistic standpoint. Whether she thematizes an individual’s right to sexual explorations (‘History Of Virginity’, 2012; ‘Éphémère’, 2013) or one’s journey to the limits of social, political, and ecological awareness (‘Newspaper News’, 2019, made at Punched Paper Films that opened in 2018 in a town of Carouge), Haller deliberately reminds the viewers that they are responsible for acquiring, understanding, and disseminating the verified facts about the world phenomena – passiveness is a wrongful deed (the words “We cannot claim we didn’t know” appear in the closing images of the last film).

But it is Milva Stutz (born 1985), Zurich-based, feminist filmmaker and visual artist, who examines the full spectrum of given and received sexual pleasures with the use of imperfect, fleshy clay figurines embedded in estranged and sterile 3D animation environments, disturbing voice-over, and other sound effects (‘My Dear Lover’, 2020; ‘For Real, For Real, For Real This Time’, 2022).

Another renowned feminist determined to change the landscape of Swiss creative industries is Manu Weiss (born 1984), animator, curator, and creator of various AR and VR immersive exhibitions (especially Animated Women: AR Portrait, hosted at the festivals Fantoche, Animateka, and StopTrik in Slovenia, and Animest in Romania).

Cross-cut of personal and political most profoundly affected the filmmaking of Anja Kofmel (born 1982). Her animated journey into personal memories, family trauma, and historical tragedy of the distant societies from the Balkan region started in 2009 when she made the short film ‘Chris’.

Kofmel dedicated the following years to developing this story into an animated, documentary, a feature-length project which eventually premiered as ‘Chris the Swiss’ in 2018. The director investigates the murder of her cousin, Christian Würtenberg, who died in December 1993 arguably at the hands of foreign volunteers of the PIV First International Unit (responsible for “cleaning” the designated areas from the Serb nationals) with the Croatian National Guard during the Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995).

Who was Chris, the idolized hero of her childhood? This independent journalist turned mercenary left behind several manuscripts (but no trace of a book about the evil rationale that pushes the soldiers to commit atrocities which were supposed to be the reason for Würtenberg’s enlisting), random tokens of being present in dismantling Yugoslavia (the bills, tickets, etc., help Komfel to reconstruct his wartime itineraries), and the fellow journalists still remember him from Zagreb. In order to represent what could have not been double-checked against the limited factual data, Anja Kofmel used means of animated filmmaking. She employed the 2D technique in creating sometimes minimalistic, sometimes nightmarish, black and white architecture of the war-torn reality.

Dramaturgical development is submitted to the logic of research – first, she asks questions, then embarks on a journey. When arriving at the former battlefield’s areas (Karlovac, Osijek) she confronts the darkest truths about Chris. At one point somebody calls him a “radically utopian humanist” who could have never comprehended that cruelty is a core element of war. But the inescapable question, “Did you believe you can document the slaughter of civilians without becoming a part of it at all?”, is posed by the voice-over on the white background.

Eventually, she reconnects with the family members who – not being filmmakers – have to find their own ways to reconcile with the past. Upon return home, she tunes the radio in and hears the news of another young man killed in the war some far away from his home. Accepting the Swiss Film Award 2019 for best documentary, Anja Komfel said: “This film was a monster”.

Swiss Animated Industry: Microcosm and the World

According to the 2020 Annual Report published by the SWISS FILMS, the national agency for the development of the audiovisual sector, 2019 was a record year for the festival screenings and awarding of the Swiss short films (p.26). A forthcoming tribute to Swiss animation in Annecy may decisively support the visibility of this animated industry.

The functioning of the structural components of the film industry (professional training, production, distribution, festival support) differs greatly when it comes to major creative categories – features aimed at theatrical and VOD distribution, art-house shorts (professional and student films), children’s production (including TV series) procure different requirements and challenges.

In general, the Swiss animators recruit mostly from the cohorts of the students and graduates of Swiss academies where animation programs are taught. HSLU – or rather: Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts – received the title of the Best Animation School at the Animafest Zagreb 2021, and indeed it has taught an extensive number of the most prominent Swiss animators. Nevertheless, animation education in Switzerland is not limited to Lucerne. One can enroll in professional courses also in Zürich, Genève, and Lausanne, and the school EPAC (Academy of Contemporary Art) holds the position of pioneer as it was this academy in Saxon that founded the first school of designing and drawing comic strips in 1993.

The production process of Swiss animations is determined by the public grant system. The filmmakers predominantly seek support from the Swiss Federal Office of Culture (SFOC) and the language units of Swiss Public Television. The most efficient strategy assumes coproduction with French, German, Belgian, and Italian partners being the most natural choices given cultural and language similarities – this feature also bears a promise of a successful, future distribution chain.

Swiss short animation enjoys esteem in the art-house world. The brands of Nadasdy (Genève), Hélium Films (Lausanne), Virage Films (Zürich), YK Animation Studio (Bern), Schattenkabinett (Lucerne), and obviously G.D.S. (Carouge), guarantee an immediate interest of worldwide animation aficionados.

Last Day Of Autumn, Marjolaine Perreten

The major festival players on the Swiss scene are few but their background is complex. Fantoche known to a wide audience as an event held annually in Baden since 2010, first started in 1995 as a biennale organized in Zurich. The financing problems canceled the event in the years 1999-2003. The void was filled by the Kurzfilmtage Winterthur (a showcase of all short cinema forms) which was established in 1997 out of frustration of “being denied industry access to existing film festivals” (Festival website, Archive 1997). Animatou (Genève) functions as an autonomous festival since 2006.

Only naturally, producing quality animations targeted at young audiences is one of the key responsibilities bestowed by the funding institutions. RTS and particular TV channels (e.g., TV5 Monde) are essential co-producers in this branch of the industry.

The studio Nadasdy is one the most prolific in children's production. The creators of ‘Dimitri’ (Agnès Lecreux, Jean-François Le Corre) sought in 2014 and 2018 the fittest episode and runtime format, and eventually, they arrived at 2 seasons and 1 spin-off, it also received a warm welcome in Annecy in 2014 and 2015. A lot of Nadasdy’s series production is realized in collaboration with the French renowned studios such as Vivement Lundi!, Beast Animation, or Folimage.

Another success story of balancing between art-house projects and commissioned work for children’s audiences is YK Animation which produced a feature film about one of the iconic characters created by Ted Sieger (born 1958), ‘Monster Molly’ (2016, dir. Michael Ekblad, Matthias Bruhn, Ted Siege). YK collaborated with Sieger again on a short 3D ‘The Smortlybacks Come Back!’ (2022).

The coproduction modus operandi is a must-be strategy for feature-length projects, the jewel in any film industry’s crown. Swiss companies functioned as minor partners in the productions of ‘Couleur De Peau: Miel’ (2012, dir. Laurent Boileau, Jung Hejin, Belgium, France, South Korea, Switzerland - Nadasdy), ‘1917 – The Real October’ (2017, dir. Katrin Rothe, Germany, Switzerland – Dschoint Ventschr, RTS), ‘The Swallows of Kabul’ (2019, dir. Zabou Breitman, Eléa Gobé Mévellec, France, Luxembourg, Monaco, Switzerland – Close Up Films), and soon premiering in Annecy ‘No Dogs or Italians Allowed’ (2022, dir. Alain Ughetto, France, Italy, Switzerland - Nadasdy).

The features that represent Swiss national cinema are already mentioned ‘Max & Co’, ‘My Life as Zucchini’ (France, Monaco, Switzerland – Rita Productions, Hélium Films, RTS), and ‘Chris the Swiss’ (Germany, Finland, Croatia, Switzerland - Dschoint Ventschr, RTS). ‘Red Jungle’ (2022, dir. Juan José Lozano, Zoltàn Horvàth, France, Switzerland – Nadasdy, Intermezzo Films) was presented for the first time in March at the Geneve Human Rights Film Festival.

It is announced that Claude Barras concurrently develops two stop motion feature projects (both in coproduction with French partners): ‘You’re Not the One I Expected’ (Hélium Films; Emilio Mayorga, Claude Barras’ ‘You’re Not the One I Expected, source) and ‘Sauvages’ (Jamie Lang, Claude Barras’, on Variety,; Nadasdy website).

One cannot help but wonder: why is it that the quantitative increase in feature production in Switzerland appears so problematic? Eventually, the audiences in the cinemas as well as the users of the VOD platforms yearn to engage with this format. What is more, the Swiss producers can count on the involvement of many professionally trained talents who have already gained recognition at international festivals.

Swiss cultural complexity stands for one of several possible explanations of the problem. The producer of ‘Airport’, Gabriela Bloch Steinmann, recalled: “My Life as a Courgette was a big success in French-speaking regions, but not in the German-speaking part, nor in Germany. It’s hard for an animation to cross language barriers’’ (Julie Hunt, Swiss animation scene needs polish, swissinfo.ch, 17.9.2018).

Steinmann further noticed another trouble of a complementary nature – on the one hand, the filmmakers are too consumed with the formal qualities of their artistic projects that they “forget” to realistically calculate the budgets and think about possible distribution practices, however on the other, the producers themselves need to become more daring and self-reliant in their pitching and pursuits for international collaborations.

At various festivals, roundtables, and forums held in Switzerland in recent years, the Swiss filmmakers made a lot of efforts to discuss, diagnose, and propose solutions to the problem. All the empowering pieces needed for the next level of professionalization of the industry and the well-being of the community lie down on the table. Soon we should see if the creative players of Swiss animation (directors, producers, and everyone involved) will reach out to them.

Contributed by: Olga Bobrowska